Young Chekhov (trans. David Hare; dir. Jonathan Kent) National Theatre, London; Aug. 2016 (and also some The Plough and the the Stars)

It was the worst of theatre, it was the best of theatre. This cycle of Chekhov’s first three plays (Platonov — heavily edited and adapted; Ivanov; and The Seagull), in new “versions” by David Hare and directed by Jonathan Kent, was celebrated in the press when it opened at Chichester last year and is now being remounted in the Olivier Theatre. I haven’t seen Ivanov yet. The Seagull is distressingly bad; the Platonov is blissfully good.

Helpful, no? Perhaps I should give them star-ratings as well.

Kent’s Seagull had a lot in common with another disappointing NT production I saw this week, Sean O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars directed by Howard Davies and Jeremy Herrin. Both featured a painstakingly detailed set, beautifully crafted period costumes, and the kind of acting that still passes for theatrical naturalism around here — well-shaped voices doing accents considered appropriate for the material, no-one digging too deep into their emotional or intellectual reservoirs, no-one trying to disturb the fiction by acting as if anything they did had contemporary relevance. Actors hiding deep in their characters. Theatre pretending not to be theatre.

The O’Casey is a very strange show. For three acts, it’s this kind of paint-by-numbers museum theatre — O’Casey safely enclosed in the aspic of historical realism. The set is as impressive as it’s meaningless, no more than accomplished photorealism (the inside of a tenement, transformed for Act 2 into the inside of a pub: it revolves to the outside of the tenement, then the inside wall of the pub flies down, then a bar flies down. Technically a bit awe-inspiring, aesthetically antediluvian. I saw Jette Steckel do exactly that sort of thing as a pretty hilarious joke about Hauptmann’s naturalism in Hamburg a few years ago…). Everyone bumbles around on stage being as Oirish as possible. And while that reminded me of Juno and the Paycock at the Shaw Festival two years ago, unlike Jackie Maxwell in that production, Davies and Herrin don’t seem at all interested in O’Casey’s proto-Beckettian patterns of verbal repetition — the verbal tics that turn his characters’ speech into something more intriguing than mere mirror images of real life.

It goes on like this for a while after the interval. Until Act 4. At which point, it feels like Judith Roddy (as Nora Clitheroe) and Justine Mitchell (as Bessie Burgess) just take the show away from their directors and turn it into something else entirely. Or perhaps Davies/Herrin just gave them free rein at that point — what do I know? In any case, suddenly, the show develops a raw power, and drive, and tragic weight, and becomes utterly gut-wrenching theatre. Roddy is magnetic — she hurls her body around on stage, she darts about erratically, she freezes, she collapses, she tunes in and out of reality. It’s a compulsive and convulsive piece of stage acting. And Mitchell (spoiler, spoiler), once Bessie has been shot, delivers one of the most extraordinary, drawn-out performances I’ve seen of a person slowly dying, raging against the dying first, then slowly fading away, the words falling apart in her mouth, crumbling into sounds and reemerging as something recognizable, and finally fading into a whisper and then a nothing. Edge-of-my seat stuff — and a huge disappointment. To think that Davies and Herrin had actors like this to work with, and to think that they did nothing with them for most of the show, screwing around with production values and a smorgasbord of clichés instead. Fools.

The Seagull is much worse, because no such turn ever comes. Everything is terribly well-mannered, but neither funny nor sad (let alone devastating). Anna Chancellor is enjoyable to watch as Arkadina, but everything’s an act for her — even the fading diva’s despair. The sheer nastiness of so many of Chekhov’s characters remains as muted as the deep affection between others. Smothered by the historicist frame and the relentlessly English politeness of it all, none of Chekhov’s punches land: Konstantin’s rage, whether aesthetic or filial, has no real purchase (partly because its targets are so very far removed from anything anyone around here might care about); the undercurrent of financial distress never carries any real weight; Nina’s fascination with Trigorin remains that of a wide-eyed provincial girl; Trigorin remains completely without contours — Kent simply ignores the critique of art’s relationship to real life and real people that this character invites; and on and on. It’s a show so superficial that it’s very superficiality would be profound if it seemed like a conscious choice. It doesn’t.

Does Kent appear to have a theory as to why Konstantin kills himself in the end? If so, it wasn’t clear to me. In more successful productions I’ve seen, it’s Nina’s unlikely transformation in the final act from a helpless victim into an independent artist (damaged and battered but finding her feet), an actor who can now give Konstantin’s flawed lines from Act 1 a theatrical power that they in themselves badly lack, that pushes him over the edge: everyone is an artist but Konstantin. He’s just en route to becoming his uncle: another “man who wanted to.” Here, nothing like that happens. Nina remains a wreck: when she says the lines about having a vocation, I at least couldn’t see any kind of transformation in her. She was still a figure of pathos and ruin. And without that transformation, I have no idea why this encounter, as saddening as it may be, would have pulled the existential rug from under Konstantin’s feet.

And then there’s the end. Until that point, the show follows Chekhov slavishly — or rather, a peculiarly English notion of Chekhov that could happily have been staged in the 1970s. And then it departs from the text, to disastrous effect. Remember how it is in Chekhov: Konstantin leaves; then everyone else comes back into the room; then there’s a bang from off stage; then Dorn leaves, claiming to check on the ether bottle in his medicine bag; then he comes back to the room full of people that have been waiting in silent suspense, announcing that everything’s OK; then he pulls Trigorin aside to tell him that Konstantin has shot himself. Here, none of that happens. The suspense, the balance of certainty and hope, the audaciousness of simply letting a cast of actors sit there, right in front of us, without having anything to do while Dorn is off? All gone. Instead, we get this: there’s a dining room upstage from the drawing room where Konstantin works. It has a glass wall and we can see (and hear) the dinner going on there while Nina and Konstantin talk. She leaves, he tears up his work, he goes to his desk and pulls out a gun. A GUN! (I was ready to shout “stop” at that point.) Then he turns his enormous desk chair so its back is to the audience (and the drawing room), climbs into it, and shoots himself. Before that (if I remember correctly), Dorn has started opening the drawing room door — the dinner has finished and people are getting up in the other room. All the dialogue that Chekhov puts on stage, though, takes place in that upstage area. Then Dorn comes downstage to investigate what has happened; he finds Konstantin; he pulls Trigorin from the dining room downstage to tell him. All the awkwardness — the silence, the suspense, the waiting — happens almost out of sight; all we see is action: Dorn moving, discovering, sharing. But suspense clearly isn’t the point anyway: where Chekhov leaves us in the same state of fear and/or hope that Arkadina et al. are in, Kent (not, notably, Hare) places us in a position of superior knowledge. What the point of any of that is… I don’t know. Why a production that seemed so careful to avoid anything too interesting, anything that might conceivably feel like a directorial or dramaturgical intervention, saw A need to refashion the play’s structure at the end — I have no idea. For one show to combine the worst kind of conventionality with the most misguided sort of inventiveness, though, is a kind of miserable achievement.

So that was The Seagull. I was so dispirited at the end of it that I was half-determined to give up on the other instalments in the cycle. And then I went to Platonov after all, and it was magnificent.

An update, half-way through writing this: I have now seen Ivanov, which was helpful. It’s almost as disappointing as The Seagull, played like third-rate Noel Coward and/or very broad farce. The nastiness is thoroughly leavened with thigh-slapping humour, all very safe, all very contained, all very entertaining. Perfect for a Saturday afternoon, including a little kip or two.

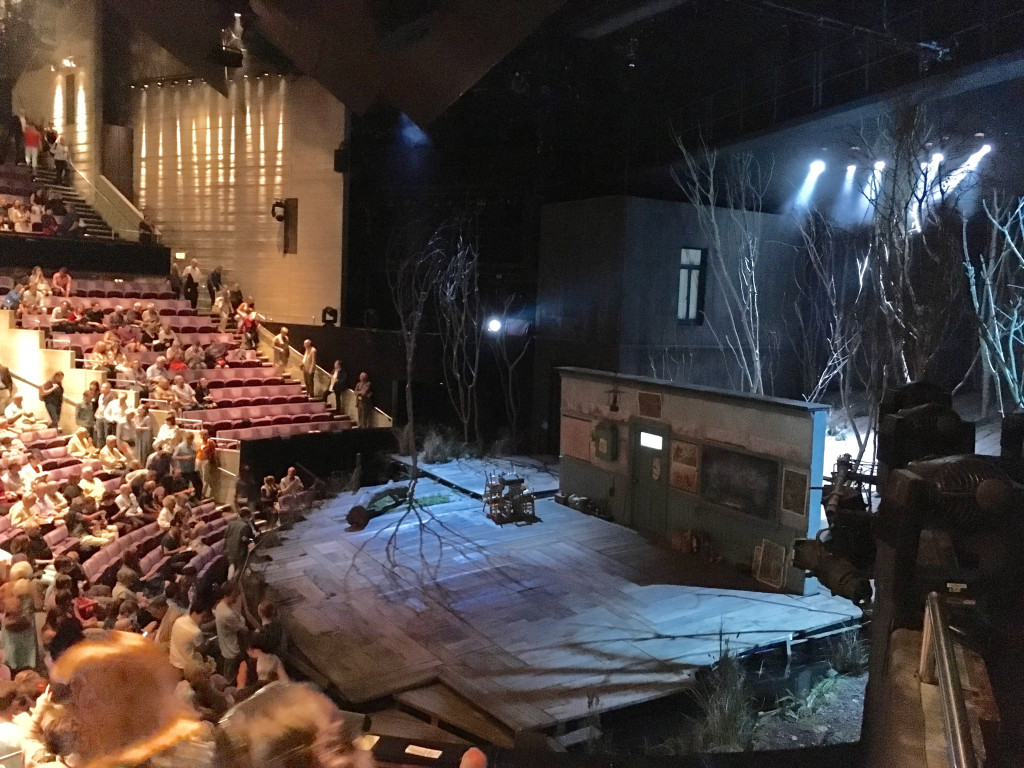

Why is that helpful? Because it confirms what I suspected after Platonov. On the surface, that show was just like the other two. Comfortably historicist. Staged in a beautifully realized set full of water features, real grass, great trees, and with marvellous hydraulic elements to create rooms and houses. Just gor-ge-ous. Enough birdsong, too, to drive poor old Chekhov mad. Lots of linen suits. All very Russia, very old world, very unthreatening, very bang-for-buck.

But something happened in Platonov that absolutely did not happen in the other two “Young Chekhov” instalments. Actors happened.

Was it that the performers felt more free because they weren’t doing “Chekhov,” but David Hare’s radically shortened version of a supposedly unstageable play, and a play written long before Chekhov became the Chekhov? Was it that Jonathan Kent directed with a freer hand because of the play he was working on? I don’t know. My instinct tells me to credit the actors, though.

And not just James McArdle. Even before his Platonov finally arrives, there’s life on this stage that simply isn’t there in The Seagull and Ivanov. Even before the play proper starts: Nina Sosanya (as Anna Petrovna) and Joshua James (as Nicolai Triletsky) are sitting centre stage playing chess during the pre-show — and they’re sitting and playing with more presence than almost anyone does anything in the other shows.

It’s very difficult to write about this sort of thing: acting. What do you say? Sosanya’s presence is fantastic. She’s quick and gracious; mercurial, generous, dismissive, welcoming — her Anna dominates every scene she’s in. No wonder half the men in the play want to marry her; no wonder almost everyone is willing to lend her money; how horrible Shcherbuk is for wanting to do neither. Sure, the power is the character’s; but really, it’s the actor’s. Sosanya plays with her scene partners the way Anna plays with the other characters in the play. There’s a joy, a freedom, a pleasure in her performance that isn’t part of the fiction: it makes the fiction possible. Joshua James plays along very nicely in that opening scene, plunging himself into Triletsky’s physical awkwardness and his compulsive jokiness with delightful abandon.

And then James McArdle shows up. Platonov is a beast: he owes everybody money, he sleeps with everybody’s wives, he cheats on his own wife, he’s a drunk, he’s a ridiculously irresponsible school teacher, he’s dirty and unwashed, he’s whiny and self-aggrandizing and a terrible, terrible man-child. Even in historical context, he’s a monster; from a 21st-century perspective, he’s completely beyond the pale. He should be utterly loathsome. And precisely why everybody seems to be going on about his astonishing mind is a real head-scratcher. And yet, in performance, it all makes sense. Sort of. McArdle is just so absurdly charming in the role — so hideously, hideously charming. So fast. So free. So physically uninhibited. So present. So… um… so Scottish.

I’m not being flip: I actually think McArdle’s aggressively in-your-face accent (how many “r”s in “trrruth?”) makes a huge difference here. Compared to the relentless gentility of the accents in The Seagull, those voices you’d never hear on the street, the sheer contemporary real-ness of McArdle’s voice slashes through the historicist screen of the production — and suddenly this show, this absurd show about an absurd character surrounded by absurd acolytes feels extraordinarily modern. Sosanya’s performance does something similar. And I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it’s the two actors who are most unlike the rest of the cast — the person of colour and the Scot — who manage to bridge the distance between Chekhov and us.

Here’s the thing: what most of the other actors are doing around these two or three performers really is no different than what they do in The Seagull or Ivanov. But it doesn’t matter. With McArdle and Sosanya anchoring the show in some kind of performative present, the other performances get pulled into the same present as well. They reorganize themselves around those central performances, and no longer feel quite so safely removed, quite so comfortably encased in their historicist resin.

And once that connection has been established, extraordinary things happen. Chekhov’s farce gains depth. Everything starts to feel positively Shakespearean: there’s a Twelfth Night-like quality to the whole affair, except that Viola/Cesario/Sebastian is a filthy, unwashed, school teacher. And then, suddenly, one character poisons herself. But lives (joy!). And then Platonov gets shot. And doesn’t live! What? The show always teeters on the edge between comedy and tragedy, making us laugh about things that really shouldn’t be funny, stopping the laughter in our throats with news far too horrible for the kind of play this seemed to be a moment ago. It’s a constant back-and-forth, until it stops cold. As a narrative, it’s completely implausible. Silly, really. But as a performance, like its eponymous non-hero, it makes brilliant sense. It’s awful, and it’s a joy to watch.

I don’t really have anything more concrete to say, which bothers me a bit. I don’t think this is a production with an argument, exactly. It is an actors’ showcase, though, and a demonstration of how a really compelling performance can undo the distancing effects of naturalist stage historicism. And it’s a demonstration of what gives performances this kind of compelling quality: not an actor’s success at vanishing into a role, but an actor’s willingness to let us see their work.

How about this as an argument: in a way, Chekhov’s play is a dramatic dare. It has a bit of a “watch me take this storyline there” attitude. McArdle’s performance (and in a less obvious way, Sosanya’s too) does exactly the same thing. No wonder the play has such wonderfully anachronistic soliloquies — not introspective talking-to-myself speeches, but proper addresses to the audience. It’s a “watch me” kind of play. And McArdle’s a “watch me” kind of actor in it. So, instead of having to pretend that we’re sitting there watching people from the 19th century, we get to watch an actor who, with a wink (at one point, quite literally!), shows us that he’s playing a character — and that he’s having fun doing and saying the outrageous things his character gets to say and do. And at that point, it turns out that the good old early modern chemistry still works: show the people that it’s all fake, and they’ll believe you even more. Show the people who you really are and they will go along with who you’re clearly not that much more. Of the three plays in the Young Chekhov cycle, the only one that affected me emotionally at all was Platonov — precisely because it didn’t ask me to buy into its fiction. Because it was relentlessly and honestly theatrical where the other two were merely being relentlessly fake.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

One Response to Young Chekhov (trans. David Hare; dir. Jonathan Kent) National Theatre, London; Aug. 2016 (and also some The Plough and the the Stars)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.

[…] Young Chekhov (trans. David Hare; dir. Jonathan Kent) National Theatre, London; Aug. 2016 (and also … […]