Sunday, 12 January 1919

And suddenly, there are newspapers again: between Saturday and Sunday, most — all? — of the occupied buildings were stormed, dozens of protesters killed in process, hundreds arrested, and on Monday, the papers all tell long, detailed stories of their occupation. Vorwärts, the Social Democratic party paper, whose building was the first to fall, appeared again on Sunday, with a four-page edition entirely devoted to the unrest, calling for mass demonstrations in support of the government on its title page.

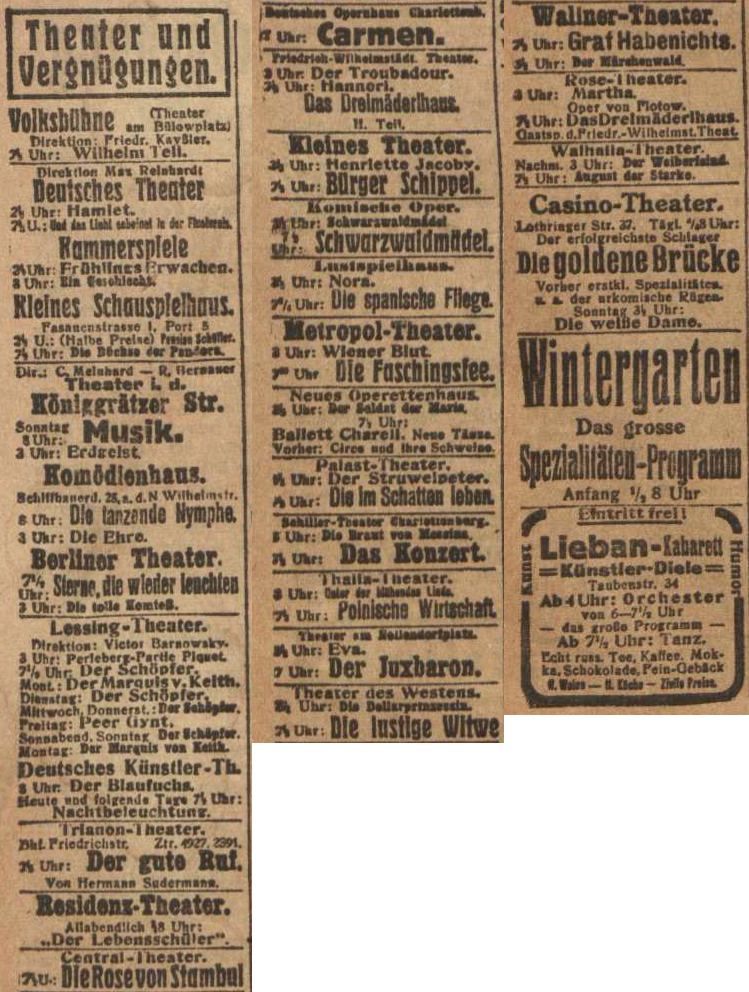

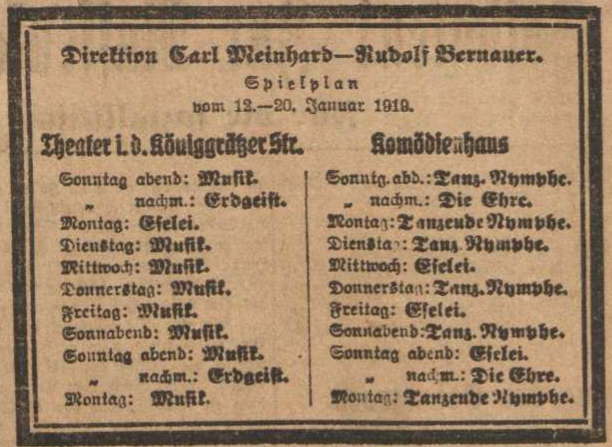

In the theatres, though, it’s business as usual. Here’s the daily listings from Freiheit, including two announcements of the programming for the week ahead (and the Staatstheater is missing again, but we know what they performed on January 12 from yesterday’s Börsen-Zeitung):

I say “business as usual” — but after my musings yesterday, I wonder if that doesn’t mean that the theatres, at least some of them, continued their mildly politicized programming during the pivotal weekend of the turmoil. The Volksbühne offered Wilhelm Tell again, and the Palast-Theater, rather than going back to The Mikado, as they had done for the previous week, ran a second night of The Shadow-Dwellers. Other than those, though, there is little going on in the theatres that seems out of the ordinary at all. One thing to note: Sunday matinees, almost everywhere! The Volksbühne Association, the organization that owned the theatre that still survives, in much modified form, today, but also organized a rich array of other theatrical and cultural events for its thousands of members, was one of the main drivers of this programming, and bought large blocks of tickets for these matinees, sometimes entire houses. As we saw before, it’s a mix of classics and fairy-tale shows, though on Sundays, the mix also seems to include popular shows from the evening repertory (such as the operetta Schwarzwaldmädel at the Komische Oper, which ran twice on 12 January — an arrangement familiar from modern Anglophone theatre, but quite unusual in Germany). Reinhardt’s three theatres all offered well-known productions from his regular repertory in the afternoon, though it’s not certain that these would all have featured the original casts: Hamlet at the Deutsche Theater, in a version directed by Reinhardt himself that had been in rep since 1913; Spring Awakening at the Kammerspiele, in Reinhardt’s 1906 staging that eventually racked up an astonishing 387 performances, far more than any other Reinhardt production; and at the Kleine Schauspielhaus, Pension Schöller, a farce by Carl Laufs and Wilhelm Jacoby that remains in the German comic repertory, and has emerged as a minor classic in the hands of leading directors such as Frank Castorf and Andreas Kriegenburg in recent decades. Like the week-day matinees for students, these Sunday afternoon shows were clearly not reserved for light entertainment: just consider that even a venue as sharply focussed on commercial froth as the Lustspielhaus chose to offer Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (or Nora, its more common German title).

Anything else? Not really, except to reiterate what I’d noted in an earlier post: just how much Wedekind there was on stage in those years. The Theater in der Königgrätzer Strasse staged virtually nothing but Wedekind, and between the two versions of Spring Awakening Reinhardt directed, that play saw almost 450 performances — a count that dwarfed everything else in his repertory, including the famous stagings of Midsummer Night’s Dream and the notoriously endless run of Shaw’s Saint Joan.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.