The Plough and the Stars (O’Casey; dir. Sean Holmes) Abbey Theatre Dublin, at Canadian Stage, Toronto, Sept 2016

This is really quick and dirty and off the cuff… Carly Maga’s excellent review in the Toronto Star (wow, it feels nice to be able to use “excellent review” and “Toronto Star” in the same sentence!) gives a quick summary of the play if you need it.

Let me just say, first and foremost, that I LOVE that Matthew Jocelyn is bringing this kind of work to Toronto, and that I wish, fervently wish, that we’d get more productions like this around here. It’s so important for our audiences and our theatre artists to get a look at how this sort of thing is done elsewhere. If nothing else, it might shift the absurd notion that the US is somehow a leading force in world theatre.

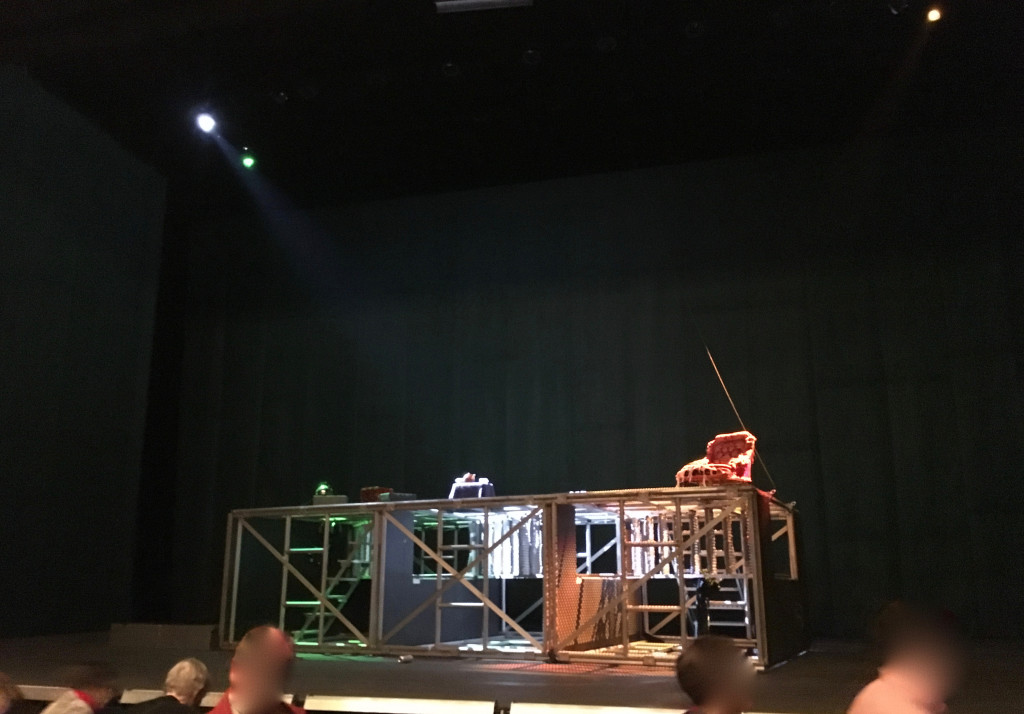

This show certainly made for a pretty staggering contrast with the museum-like piece of dead theatre that was the Plough and the Stars that I saw at the National Theatre a few weeks ago. Sean Holmes’s production uses modern costumes (mostly) and a wonderfully flexible and ramshackle set centred around a tower of scaffolding. Lots of songs sung into a mic that’s just hanging out on stage. People who just sound like they’re Irish rather than stage-Irish (still lots of struggles to make sense of what they were saying among the people around me…). Plenty of direct audience address, though that felt forced to me: it’s one thing for a character or an actor to speak straight out, and that happens quite a bit too; it’s another to speak to the audience in a tone that seems to allow for a response. With one exception, I didn’t think that an actual response was what they were looking for…

Act 4 set (the tower of scaffolding has fallen). My own illicit snapshot. All the production photos are awful, completely misrepresenting the spaciousness of the set.

One curious thing, though: at the NT, the fourth act blew me away. Perhaps that was because what came before it was such clichéd dreck. I don’t know. But at the Lyttelton, sitting well back from the stage, I was at the edge of my seat, horrified by Nora Clitheroe’s agony, breathing along with Bessie Burgess’s dying words. At the Bluma, four rows back, I wasn’t especially riveted. And that, I thought, was a bit of a shame. I also, as a consequence, didn’t feel the same intense loathing for the British soldiers. That, too, was a shame.

Holmes’s take on the play is much more cynical than the NT’s relentless jollification of everything. The scenes of looting framing the dying ICA soldier in Act 3 were quite horrifying — kind of impossible for those characters to recover from the contrast between their naked consumerist greed and the soldier’s onstage death. But they sort of do, theatrically: Mrs Gogan’s flights of fancy when she recounts her horrible death nightmares are just so hilarious that it’s easy to forget what a monster she also is. Fluther Good’s fight with a spraying beer can is such a delightful clown turn that it kind of rescues the character, too. That happens a lot in this show: people do and say seriously awful things but then they’re also seriously funny, or the actors are seriously funny, and the distance of humour somehow undercuts the awfulness. But that only goes so far. Still: much better than at the NT, where the nastiness was completely smothered by all the folksiness. In the Abbey production, the ugly stuff hit hard, even when it was immediately followed by a laugh.

Where the distance becomes a bit more of a problem is in the tragic parts. Not always, mind: like the very top of the show. There, Mollser, Mrs Gogan’s consumptive daughter, opens things with an instant showstopper: her plaintive rendition of the Irish national anthem, alone, before the curtain, in the spotlight, is interrupted by her coughing — and I thought that was funny. Until she started spitting blood onto the sheet of lyrics she was clutching. But moments like that were few and far between: moments where the show pulled the rug out from under our feet, made something seem funny to reveal that we really should’t be laughing. Or moments that just sat in their deep, desperate sadness. That’s not really Holmes’s register, at least not in this show.

Mollser continues to appear between scene changes, for the last time with a desperate and cut-short rave-like dance after Act 3. But that she dies right after this, off-stage… well, to me at least, that didn’t have quite the heft I wanted it to have. If anything, it’s further undercut by her coffin just sort of being plonked down during the scene change (and now I wish I’d taken notes: I think it was the actor playing Mollser that brought the coffin on. I think she seemed angry, or at least grumpy. But if you don’t know who’s in the coffin, I’m not sure that read at all. And I may be making it up anyway.)

Most problematically, Nora Clitheroe’s deep need for her husband to stay home, to not go back to fighting, never quite took centre stage; her pregnancy goes almost unnoticed; the moment when she starts bleeding after Jack leaves her again is both rushed (in a show that otherwise takes so much time with things!) and oddly staged (why does Kate Stanley Brennan show her bloody hand to US? Why pull the audience in at that moment? Or rather, why make us so theatrically self-aware at that very point?); and finally, when Nora slips into delusion in Act 4, her breakdown didn’t quite find a theatrical form as radical as her transformation: she just sort of wanders around and no-one seems too terribly upset by the fact that she’s clearly inhabiting a fantasy universe. That, too, may have something to do with the various distancing manoeuvres Holmes uses throughout: perhaps it’s harder on a stage that doesn’t exactly signal “realism” to come across as really mentally unstable. Or perhaps getting there would have required larger theatrical gestures than these actors were prepared to perform.

Because for all its continental European aesthetics, I have to say that this remained a safely Anglo production. No violence was done to O’Casey’s text. While adopting a slightly more demonstrative style of acting than might be expected in most mainstream theatre in English, no one really broke out of the mould of psychological realism. If anything, the show’s charm had a lot to do with characters/actors just inhabiting the space — taking a long time to have their tea, say, or taking forever to put on a uniform.

Where this contrast between an aesthetic that at least flirted with radical adaptation and a a dramaturgy that absolutely did not became a bit of a problem for me (other than in the distance-where-distance-seemed-counterproductive moments I talked about earlier) was in figuring out what to do with O’Casey’s actual historical reference point. Nothing except for the ICA uniforms places this show in 1916 — nothing except for the text. And I think I get it: the visual updating, together with the address to the audience, is all designed to implicate us, to turn the events of 1916 into (simply?) another instance of armed conflict, nationalist fervour, egocentric profiteering, and so on, rather than the central point of the play. For a modern audience, I take Holmes to say, the specific fight of 1916 doesn’t matter so much anymore; what O’Casey has to say about that is only relevant now to the extent that it can be made to speak to a larger, more general debate about ideals and political/military/private realities (including a very obvious clash of apparent political progressiveness and gender-political regressiveness).

That appeal to us — to turn the gaze of the show not onto history, but onto ourselves — is very overt at the very end, when, as the British soldiers are singing “Keep the Home Fires Burning,” the entire cast, many in bloodied outfits, return, stand downstage, and stare us down (daring us to applaud?). We’re here, they seemed to say: you’re there. Time to stop looking at us and to start looking at yourselves, and the many times this kind of story has played out in the century since the Easter Rising. That, I think, was the point. And sometimes that point came across loud and clear. But at others, the relatively timid dramaturgy kept the show’s text so deeply grounded in 1916, or perhaps 1926 (when it was first staged), that making that leap from then to now was much harder than it should have been.

And in those moments, I was reminded that I wasn’t watching a production from the Abbey Theatre, not from the Schaubuehne (the German theatre where this kind of show would most likely run). Not that there’s anything wrong with that….

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.