Post-Curtain Theatre History

I suspect that my generation of theatre historians will look back on this day as a game changing moment: the Curtain has been dug up in Shoreditch, and it’s nothing like what we expected. I’m too young to remember the announcement of the Rose dig, which also shattered a lot of received narratives. It probably felt similarly revelatory. But I think today’s reports might prove more fundamentally important still.

Here’s why. The most basic thing everyone has always known about early modern outdoor playhouses is that they are round. They’re not, of course: they’re polygonal. But whatever. They’re round enough. The “first” of them was round: the Theatre, built by James Burbage in 1576. The first in Southwark was round: the Rose, built by Philip Henslowe in 1587. The most impressive (if commercially doomed) of them was round: the Swan, built by Francis Langley in 1595. The most glorious of them all was round: the Globe, built by the Burbages and their friends in 1599. And the smelliest of them was round: the Hope, built by Philip Henslowe in 1613. Playhouses were round — except for the weirdo among them, the Fortune, bizarrely built on a square plot, by Henslowe and Edward Alleyn (who surely should have known better), in 1600.

And now the archaeologists of the Museum of London have gone and shattered that narrative, announcing that the foundations of the Curtain, exceptionally well-preserved, show that it wasn’t round at all, but a rectangular building measuring about 30 by 22 metres.

What that discovery reveals is not simply a fact about the Curtain. It allows for a completely different genealogy of early modern theatre spaces — one that not only links playhouses more directly to the Inns within the City of London that were also used for theatrical performances until the end of the 17th century, but that also can now recognize that rectangular or square playhouses weren’t outliers, but just as “normal” as round ones.

The Fortune’s never been as much of an oddment as its typical description makes it appear. Even though most standard accounts have always described it as “unlike most other public playhouses” (or some such phrasing) on account of its shape, that was never actually an especially accurate thing to say. But now that the Curtain, one of the oldest and the longest-surviving of early modern London’s theatres, also turns out to have been rectangular, the narrative has shifted in a way that may make all the other similarly-designed playhouses appear as just as normative as the round ones.

Here’s a list that may help:

| 1576 | The Theatre | Round |

| 1577 | The Curtain | Rectangle |

| 1587 | The Rose | Round |

| 1592 | The Rose expanded | Rounded rectangle |

| 1595 | The Swan | Round |

| 1599 | The Boar’s Head | Rectangle |

| 1599 | The Globe | Round (but an old design) |

| 1600 | The Fortune | Rectangle |

| 1604 | The Red Bull | Rectangle |

| 1613/4 | The Hope | Round |

There were also the Red Lion (1567) and the playhouse in Newington Butts (1575? 1577?), but we know nothing of their shapes. However, the playing yards at the Inns in the City where plays were performed were certainly rectangular, not round: the Bell Savage, the Bull, and probably the Cross Keys (the Bell had an indoor hall — also not, as far as we know, round).

If the Theatre set the model for round playhouses in 1576, its influence can be traced through the first two South Bank theatres, the Rose and the Swan, to the Globe (which was an expanded version of the Theatre, built out of the same wood, and couldn’t very well have been reinvented as a rectangular building), and finally to the Hope. Rather remarkably, if that’s the genealogy, the “round playhouse” type suddenly starts to look like a south-of-the-river convention.

But with the appearance of a rectangular Curtain, we can now sketch out the influence of a competing paradigm, which produced just as many independent structures, and only one fewer than the round paradigm even if we count the Globe as an entirely separate building: the Curtain, in that view, spawned the Boar’s Head, the Fortune, and the Red Bull. It may even be said to have influenced the shape of the expanded Rose — a theatre that, after 1592, could hardly be described as “round,” was barely “egg-shaped” (as one scholar called it), and really looks more like a rectangle with rounded corners.

That second paradigm is at major disadvantage, though: unlike the first type, it can’t really lay much of a claim to Shakespeare, and lacks the magic fairy dust of his “wooden O” metaphor. On the other hand, it was arguably more deeply rooted in an English tradition that staged plays in rectangular inn yards and, in the 1610s, shifted some of its focus indoors — and into spaces that were predominantly rectangular.

That’s the macro-narrative this new discovery gives a major shot in the arm. But I think the received account of the Curtain itself will also have to be rewritten. Far from the Theatre’s smaller, meaner, less impressive neighbour, it would seem to have been one of the very largest playhouses ever to be built in London. Perhaps that size gave it a versatility that explains its longevity? Here’s another list, giving the size of the area between the inner walls of playhouses that have either been excavated or described in sufficient detail in historical documents:

| 1576 | The Theatre | 163 m2 |

| 1577 | The Curtain | 323 m2 |

| 1587 | The Rose | 148 m2 |

| 1592 | The Rose expanded | c.205 m2 |

| 1599 | The Boar’s Head | 281 m2 |

| 1599 | The Globe | 259 m2 |

| 1600 | The Fortune | 282 m2 |

| 1613/4 | The Hope | 201 m2 |

In words: the Curtain was big. Very big. Almost twice as big as its neighbour. Bigger than the other rectangular playhouses. Much bigger than all of the round ones that have been dug up — unless the Globe had 18 sides and an inner diameter of 21.5 metres (the archaeologically less likely scenario). If the Globe was in fact that big, it was a bit larger than the Curtain, at 360m2. But still: it looks as if the Curtain may have been in something of a league of its own.

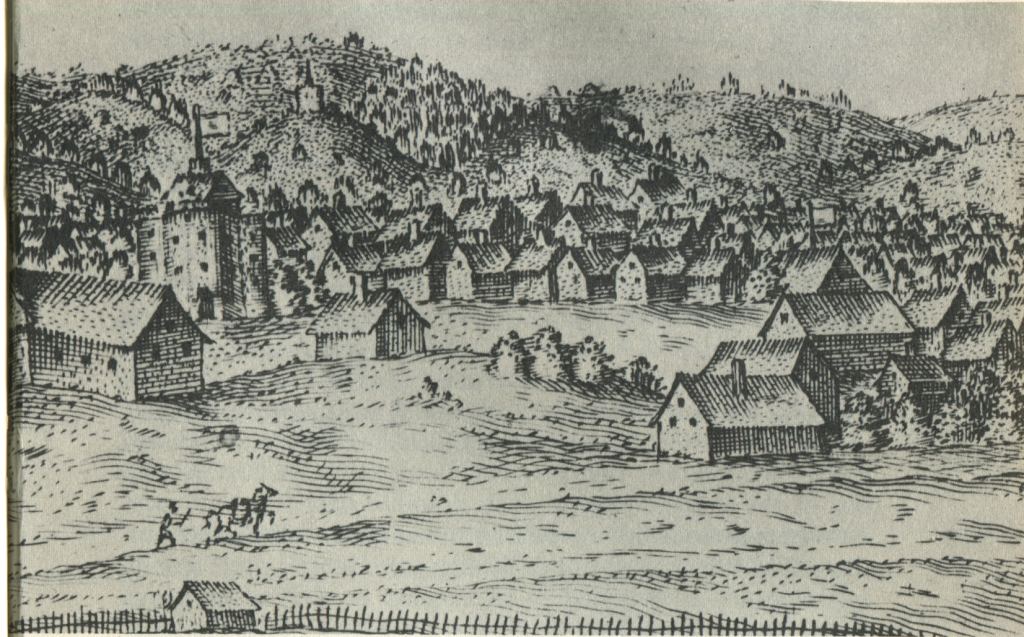

The single image that has been identified as a depiction of the Curtain, the undated (but probably Jacobean) “View of the Citty of London from the North towards the South,” does show a fairly imposing structure:

Although that building has been described as polygonal or “octagonal,” it may in fact be a poorly rendered rectangle — or a rectangle with a stair turret jutting out from it (I have no idea if the archeological evidence would support such a reading). Whatever its shape may be, the Curtain in this print dominates its neighbourhood; and if the dimensions indicated in today’s reports are accurate, that impression will have been confirmed. The Curtain as a very large theatre indeed. (Which leads me to believe that the AP report on the findings gets its facts wrong when it claims that the Curtain could have held only “1,000 people” — it would easily have been three times that!)

There are other aspects of the findings that raise intriguing questions: since it seems that the Curtain repurposed the walls of other buildings (foundation walls?), it is possible that it wasn’t built from scratch, like the Theatre, but was an early conversion project — perhaps like the Boar’s Head. I’m not sure I find this enlightening in quite the same way as Julian Bowsher, whom the AP quotes thus: “‘Out of the nine playhouses that we know in Tudor London, there are only two that have no reference to any construction,’ he said — including the Curtain. ‘It’s beginning to make sense now.'” Major conversion projects don’t necessarily leave fewer theatre-historical traces than brand new buildings: the Boar’s Head conversion has a paper trail, and even the very poorly documented Red Bull conversion comes with a moderate archival record.

But it does seem significant that most of the rectangular playhouses were perhaps fashioned out of an already existing structure — in that regard, the Fortune remains the odd one out. That said, if we can now think of the Fortune as deliberately following an established paradigm, and perhaps deliberately diverging from the South Bank “round playhouse” type, then it seems that it may not have mattered how a theatre was made, but what it became. There is certainly no evidence in travellers’ reports that visitors to London distinguished between theatres on the basis of their method of construction — or, it now appears, on the basis of their shape. Round or rectangular, newly built or converted, they were primarily noteworthy for having multiple galleries and being impressive spaces.

In fact, the Curtain may have been unusually impressive. Louis de Grenade, who wrote about his year in London in 1578, had this to say: “At one end of the meadow are two very fine theatres. One of which is magnificent in comparison with the other and has an imposing appearance on the outside.” Before today, we would probably all have jumped to the conclusion that this magnificent building must have been James Burgage’s Theatre, future home to Shakespeare and the Chamberlain’s Men. After today, I’m not at all sure that there is any justification for such a wishful thought.

On a different note, I don’t believe for a second that a bird whistle found in a building used as a theatre into the 1620s may have featured in Romeo and Juliet. So don’t call me an uncritical reader of these announcements.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

15 Responses to Post-Curtain Theatre History

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.

[…] Holger Syme explains the implications in excellent detail, with comparison charts, in his “Post-Curtain Theatre History” […]

Thank you, Holger, for this illuminating pos!.I was wondering thus if the size of the playhouse influenced the the size of the stage as well. Is it possible to speculate about thisfrom what has been found during the excavation? I can imagine that the pillars needed extra foundation in the ground.

We know that in 1585 Henry Laneman, owner of the Curtain, entered into some sort of arrangement with Burbage and Brayne whereby they took the Curtain ‘as an esore to their playe house’. Laneman apparently wanted out, perhaps because for him the Curtain was more a headache than a blessing. This new discovery invites one to wonder if the very size of the Curtain made it a financially challenging operation. All the more interesting to wonder, then, how successfully Burbage managed two such disparate buildings.

It’s a complicated and puzzling arrangement, no? I wonder if it wasn’t about a tis-sharing across the two playhouses — otherwise, I’m not sure how the profit-splitting makes all that much sense. It certainly feels like a realization, 8 years in, that competition isn’t good for either house. I’m not sure I’m quite convinced that Burbage and Brayne actually took over the running of the Curtain at that point — though the evidence can be read that way, I agree. (It’s been while since I read _The Business of Playing_ — was that the argument you were proposing there?)

I’m fascinated by the size question. That, too, I think, can go either way — a half-empty playhouse is a turn-off even if it’s not necessarily a financial burden; on the other hand, the potential income when a popular play was staged may have compensated for that.

I’ve just heard from Alan Nelon, who’s in London, and has this to add about the presumed Curtain foundations: “I met Julian Bowsher last night and he said he’s not entirely convinced. I suppose it would take something like the foundation of a stage platform to be certain; or the inner and outer foundations of a gallery. So the final conclusion is pending.” I guess caution is the proper word at this point.

Hi, i was at that same Henslowe symposium and heard the deafening silence from Jullian Bowsher on not confirming the shape. I am unaware of the double size that you give. Where do those figures come from? Conjecture remains that when how and what Burbage or Laneham did is missing from the historical record. Henslowe whose ‘diary’ we have is as much an enigma as those.

The dimensions were reported on the MOLA blog (linked in the post). My area calculation assumes a standard gallery depth of 3.8 metres (as reported present at the Curtain after the initial dig).

For all other theatres listed, the area calculations use the dimensions of those theatres as established in digs since the 1980s (for the Theatre, the Rose, the Globe, and the Hope). For the Boar’s Head and the Fortune, I used documentary evidence as reproduced in Glynne Wickham, Herbert Berry, and William Ingram, eds. English Professional Theatre, 1530-1660. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

I think it’s obvious that we know very little of what Burbage and Lanham were doing; I think calling Henslowe an enigma, though, is dangerous. If Henslowe is just one big mystery, we really know nothing at all about early modern theatre.

I thought the inner and outer foundations were there — at least that was reported after the first dig, and I thought confirmed in the recent reports.

Thanks Holger for the quick response. Twice the size and 3 times the audience huh. The MOLA blog doesn’t impress me with what it reports (especially that whistle conjecture). The dig does. And right now a Shakespeare theatre archaeologist is saying nothing about shape or size. And contemporary knowledge afaik refrains from stipulating it being twice as big as the Theatre. The Fortune was Henslowe’s response to a ‘has to be bigger than the Globe’ theatre. Also i thought the flag to the right of your image was always judged to be the Curtain. The image title may be misleading. This is more like a view of the North from the South. looking towards Hampstead Heath and Highgate. I am unaware of any hills running down to the river. As for Henslowe as enigma: we can’t decipher his accounting system, or say for sure how much monies he made from theatre. Nor can we understand his ‘diary’. Not to mention extra-curricular (ie of no interest to theatre historians) bear baiting, or the brothel(s) or the 30 properties he owned in Southwark alone. This makes him an enigma in my book. Not dangerous just uncharted in his entirety. His valuable additions to our knowledge base concerning the EM Theatre are indisputable.

Hi Holger, a quick follow up. I just returned from visiting the site of the Curtain. Couple of things: rectangular 20 by 30 is from entrance to back of the building, so including the backstage area which appears to knock the size down to 20 by 20 with galleries on all 3 sides, 3 high. It’s built on the site of the old priory garden with the garden wall serving to divide the stage from the tiring house. Our guide happened to be the chap who found that silly whistle (actually found in the alleyway outside the official theatre area) was very funny and congenial. His guess-timate for capacity was 1500 squeezed in tight. Truly from inner gallery wall to inner gallery wall you feel the narrowness. Our guide is also using the frenchman’s visit and the description of a large and a small theatre and their official line of patter is the Theatre was the bigger. I did take some photos but they aren’t very good. I ended up buying Julian Bowsher’s book Shakespeares’ London theatreland: archaology history and drama with a chapter on the curtain he now has to revise.

PS if the bird whistle is real and was found in the yard, mightn’t it have used by spectators to jeer (or perhaps praise) the players?

Maybe, Randall — and I rather like that idea. Or maybe it was a toy some playgoer had bought for his or her kid, and then accidentally dropped. Or a thousand other scenarios. But had it been a company property of any value to performance, it would not have been found there. And frankly, the further speculation that when R&J are talking about birdsong the audience *needs to hear* an actual birdsong is as silly as the notion that you need someone to play the moon in _Pyramus and Thisbe_.

Agreed, Richard, hence the scepticism. My speculation was more fanciful than serious.

My thought on first glance was that perhaps this was one of those D’Elbows mentioned repeatedly by Katherine and Alice in _Henry V_. Or Richard III’s artificial hip made of glazed terra cotta. Just hunches. Some may disagree.

Thanks very much, Holger, for this lucid summary of the new Curtain discoveries. I share your scepticism about the bird whistle!