In Praise of the Proscenium Stage

There is a conviction that haunts the English theatre: that proscenium stages create distance. That they create a fourth wall. That they are ultimately, somehow, undemocratic. And that all the ills of the proscenium stage, that withdrawn, closed-off, elitist monster, are remedied by the thrust stage — welcoming, reaching out to the audience, refusing to privilege a single perspective, placing the actors in our midst. Shakespeare’s stage. Second best, if a thrust isn’t available? A black box. Small. Intimate. No division between players and spectators. Close quarters. Personal. Intimate. And again, therefore, democratic.

This is all a load of twaddle. Not because it isn’t, sort of, true — thrust stages can, of course, produce great audience/actor connections, and black boxes can, of course, be intimate spaces. But because it sees a problem where there is none. Spaces don’t create connections. People do. (Some spaces may force actors and audiences accustomed to their separate spheres to renegotiate their relationship, but there’s no such thing as a foolproof space: actors can always refuse to connect; audiences can always refuse to pay attention.)

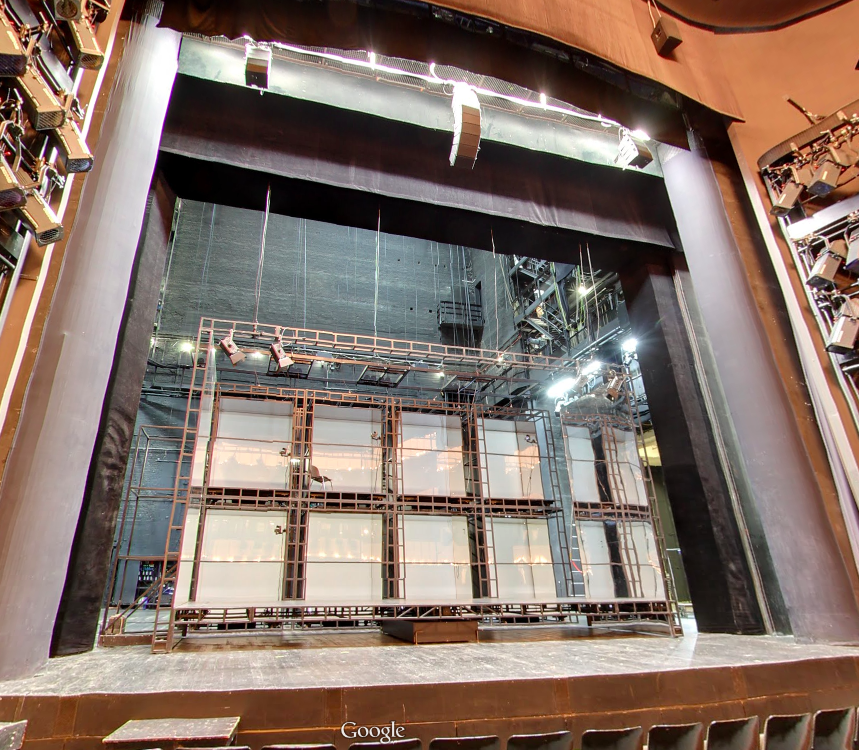

The more time I spend in German theatres, the more I miss proscenium stages. Practically all major theatres here are of that type. I’ve not seen a single thrust stage. And yet, what remains most astonishing to me about German acting is the ease with which these players connect with their audiences — through and across those supposedly distancing prosceniums. (Go ahead, explore one of those places: the Thalia’s brilliant Google Maps tour lets you do that.

Of course, there are other reasons for loving proscenium stages. Visually, they allow for a much more interesting approach to creating stage images. Their depth makes perspectival effects possible that can’t be achieved in other configurations; the distances they let directors put between characters (and between actors and audience) make them the most theatrical of spaces. Most thrillingly, they can be left empty. A thrust stage without scenery doesn’t become more or less interesting — it’s not actually empty. It just doesn’t have anything on it. The space behind a proscenium, on the other hand, is designed to be filled with scenery, with flats, with elaborate sets — but it doesn’t have to be. And when it’s not, it becomes an eloquent kind of empty space, a space that in its vastness, its hollow cavernousness speaks of memories, of choices not made, of all the illusions not created; there is something profound about watching actors build their living fictions inside and in front of this kind of purpose-built cave, with its ropes and ladders, its catwalks and stage doors, its shabby black walls lined with electrical cables.

And there is something essentially theatrical about this experience. None of it translates to video. You have to see it live. The time it takes for an actor to cross from the back wall of one of those stages all the way downstage, the effect of a murky little figure emerging from the gloom into the brightness of what are no longer the footlights; the extraordinary quality of light in an empty proscenium stage lit from on high, with a sharply focussed spot cutting through the expanse of nothingness between actor and element or the glow of a huge wash; the way fog can fill these huge caverns in no time at all, the way it can swirl and float freely, the time it takes for a layer of fog to drift up and up and up, endlessly, until it disappears into the yet deeper recesses of the fly; what it looks like when a set defends from the fly, slowly, surreally (in Jette Steckel’s take on Gerhart Hauptmann’s Rats at the Thalia Theater today, a whole kitchen/bathroom flew down while one of the actors was having a shower inside it) — none of these things can be captured adequately on film.

But as wonderful as all these effects are, none of them come close to the extraordinary things that can happen to actors on a proscenium stage. I’ve seen it over and over, and it never fails to take my breath away. A player approaches the edge of the stage and looks out into the auditorium. Perhaps she looks us in the eye; perhaps she doesn’t. Perhaps she looks down into the stalls; perhaps she gazes up into the upper circles. But she stands, facing us, the vast, crushing expanse of empty space behind her. And somehow, that enormous, empty backdrop doesn’t dwarf her — it amplifies everything. The actor, surrounded by cavernous emptiness, grows to fill that space.

It’s a genuine marvel. A theatrical wonder. It’s nothing like what happens, say, in the Globe — actors can draw attention there, too, and that has its own marvellous power. But I’ve never felt quite so amazed, quite so dumbstruck as I have in these German theatres with their empty proscenium stages. It doesn’t even have to be a particularly good show: tonight’s Rats was a very mixed bag. But I had multiple moments of being utterly transfixed by that proscenium magic: an actor, alone, at the edge of the stage, vastness behind her; her voice reaching out into the auditorium; her presence expanding beyond her body’s actual, comparatively tiny dimensions. The actor in those moments stands on the threshold between the expanse of the auditorium and the even greater expanse of the stage, the space we can glimpse but can’t physically enter — and I’m certain that the actor’s presence owes much to this liminal position, her ability to speak to us right from the edge of that magical sphere we can see but don’t inhabit. There is no fourth wall there. But there is a divide, a membrane perhaps, a window, a magic mirror.

There is nothing else like it. It is, to me, the ultimate theatrical high. And it doesn’t take much: just a great actor, a lot of space, and an arch.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

3 Responses to In Praise of the Proscenium Stage

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

Recent Comments

- Die Berliner Volksbühne: Ein Zentrum für politisches und experimentelles Theater - Kunst 101 on What’s so special about German theatre: Part 1

- My Homepage on Shakespearean Mythbusting I: The Fantasy of the Unsurpassed Vocabulary

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.

[…] I have since read a blog – ‘In Praise of Proscenium Stage‘ http://dispositio.net/archives/1915. I appreciate what is said, and although I assume nothing against the pros’ artistic value, […]

TV and film are the modern proscenium stages but I don’t hear anyone complaining about not being able to “make a connection” to the viewers. The connections made in TV and film can be most dramatic and heart-felt.

Double pros. the way to go: see Bayreuth. Amphitheatres too: see B and the Prinzregententheater. German stages and crews are funded generously. They are sites of pride and love. Some Intendants, however, are no more than epigones. There’s no such thing as parthenogenesis.