Kabale und Liebe (Schiller/Simon Solberg), Schauspiel Köln, April 2014

I’ve just embarked on another marathon in German theatre. This year, I partly want to see just how marked (if at all) the difference are between theatre in Berlin and the rest of the country. Last year, I repeatedly heard that because directors travel so much and even actors aren’t quite as stable in their ensemble affiliations as they used to be, whatever aesthetic distinctions once existed between the centre and the periphery, between East and West, between North and South, have largely disappeared. Then, in October, I discovered that despite travelling directors and despite casts featuring many prominent German actors, things feel very unlike Berlin at the Burgtheater in Vienna — so there does seem to be some sort of local spirit that influences theatre aesthetics as much, or perhaps even more than, the personnel involved. Now I’m in Cologne (and I’m also going to Hamburg, Stuttgart, and — of all places — Mannheim) to see whether that local spirit holds as much sway within Germany as in different German-speaking countries.

So far, one show in, it doesn’t. Simon Solberg’s production of Schiller’s Kabale und Liebe would not have felt out of place in Berlin (except at the Berliner Ensemble…). In many ways, its aesthetics had much in common with Lars Eidinger’s Romeo und Julia (a bit of a random example, but the closest parallels among all the shows I saw last year — in fact, it’s probably fairer to say that Solberg, a much more experienced director than Eidinger, is one of the people who’ve established a directorial approach that Eidinger followed). That the acting style felt familiar shouldn’t have been a surprise either: four of the five leads had strong connections to Armin Petras and/or his Gorki Theater (Petras moved to Stuttgart this year, which lead to a bit of a dispersal of his Gorki team and ensemble — the former chief dramaturge now holds that position in Cologne), and the fifth is an Ernst Busch graduate. Accordingly, a lot of the aspects of the work I admired so much at the Gorki last year were in evidence in this production as well: a general commitment to playing, an ability to switch rapidly between evidently text-based work and seemingly free improvisation, a readiness to combine fairly formal vocal production with the looseness of everyday speech, an openness to the audience, a delight in destroying things on stage, and so on.

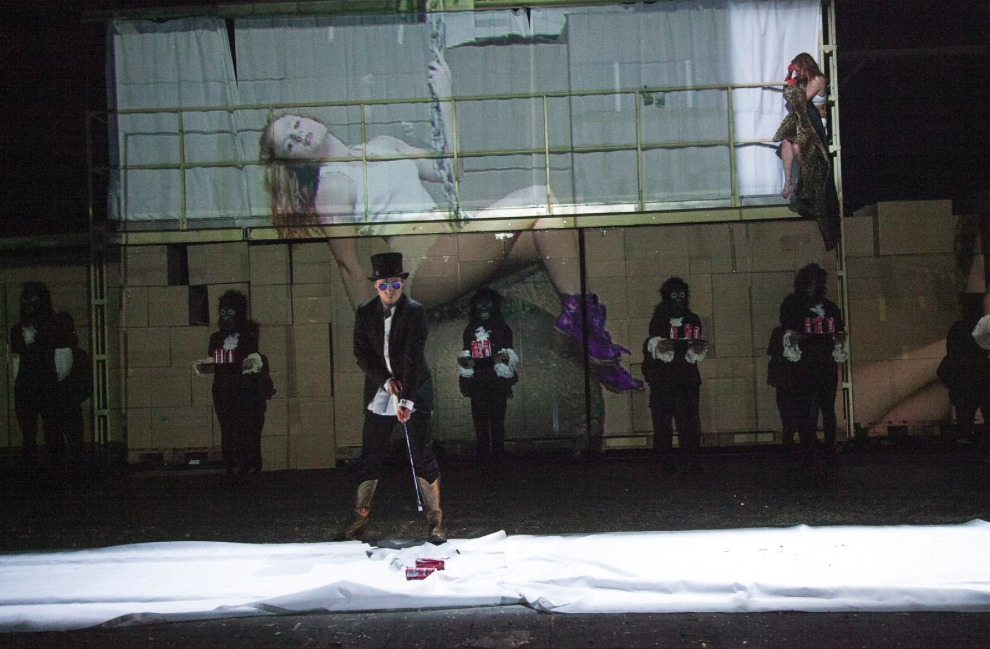

Where Solberg’s Kabale und Liebe differed from any Gorki show I’ve seen, and from most productions that could be staged in Berlin was its scale. The Cologne theatre is undergoing major renovations; in the meantime, the company occupies a vast and cavernous post-industrial space, easily 30 metres wide and deep. The show starts, appropriately enough, in a warehouse: President von Walter is not a courtier here, but a CEO (of Amazon.as), and the set consists largely of cardboard boxes of all sizes, wheeled about on palettes, variously revealing a baby grand, becoming storage lockers, thrones, caves, and serving as projection surfaces. The acoustics of the space must be challenging, which may be why the actors wore mics — though Solberg’s evident interest in creating a multimedia soundscape also pretty much required amplified vocals. A team of “warehouse workers” move the every-shifting set elements around, double as worker characters, doctors, nurses, dancers, camera operators, and street protestors. Nothing about the production signals an interest in the original context of Schiller’s play, although it is a remarkably faithful take on Kabale und Liebe, much more powerfully so than the miserable production I saw at the Berliner Ensemble last year; only at the very end does the show tip its hat to the author, when von Walter and his minion Wurm suddenly appear dressed in 18th-century costumes (even as they operate two video cameras), and when Wurm, creepily triumphant, morphs into Napoleon for the final tableau.

Conceptually or visually rigorous this production is not: the set may suddenly become Frederick the Great’s Sanssouci for the final scene, but that doesn’t stop Solberg from bringing on a squad of servants wearing (of course) gorilla masks, having Ferdinand force Luise to reenact Miley Cyrus’s Wrecking Ball video, using Coke cans for Luise’s infamous lemonade, or giving him a fire extinguisher labeled “Captialism” in the Coca-Cola typeface to wield. It’s a production that restlessly jumps from one (pop) cultural reference point to another, from a twerking Wurm to a staging of the interview between Lady Milford and Luise as “Milford’s Next Top Maid,” from tanks rolling (where?) to shots of blood-diamond miners, from prisoners with black bags over their heads to CEOs endlessly practicing their golf swings. The politics of the piece are clear if not especially original, and not exactly biting; and the sheer quantity of ideas and images is as chaotic and messy as it is impressive. Solberg’s is an aesthetics of accretion — when it works, it’s magnificently layered and complex; when it doesn’t it’s clunky and incoherent.

The failures are most evident in the beginning, when Wurm’s attempts to persuade Luise’s mother (played by Sabine Waibel, who also doubles as Lady Milford in a casting decision that I can’t quite make sense of) to intercede with her daughter on his behalf involve him pointing a 70s-style remote at the sky to switch between different songs and to trigger a dance interlude that has him grinding on Frau Miller’s thigh. Much of this seems terribly forced, and technically less than smooth, and not just because Wurm is socially awkward (lines of dialogue broken up by bits of pop-culture detritus don’t make for the most compelling rhythm). But once the show finds its pace, it becomes much easier to ignore bits that don’t quite work or don’t quite seem to fit — if only because there’s always something else to pay attention to, or because the next idea or image is always about to appear. Sure, some of those images are either a little trite or a little obvious: it’s not exactly a stretch to imagine Ferdinand and Luise celebrating their socially doomed love by fancying themselves on a lost island, surrounded by the sea; or inside a warmly-lit cave, hidden from sight by a curtain (though not from us, thanks to the video projection above their heads). But putting those imaginary scenes, those metaphors for seclusion, on stage not so much by completely literalizing them, but by using a bunch of stacked or ripped cardboard boxes — by giving, in other words, the actors something to play with? That’s less predictable, and at times positively charming.

In the second half of the play, Solberg finds a recurring leitmotif in Miley Cyrus’ Wrecking Ball video, which becomes this show’s version of the false love letter Luise is forced to write to save her parents from imprisonment. (Here, it’s just her mother, of course, whom we get to see and hear through a night-vision video feed from prison — another predictable but in its predictability, even inevitability, and in its cultural resonance very effective image.) Instead of writing the letter that is supposed to show Ferdinand that she is faithless and promiscuous, she is forced to record a lascivious video (though a less explicit version than the original, as one critic noted, calling it “surprisingly prudish“) and speak parts of the letter as a voiceover. Ferdinand watches the clip, projected on moving and shifting cardboard walls; in his final confrontation with Luise, he first projects the video over the full width of the stage and then, as a wrecking ball drops from the fly, makes her reenact her performance. It’s not that Luise is Miley Cyrus (obviously); nor is it, I think, that the lyrics of the song have all that much to do with the situation — although the song’s themes of broken hearts and people as wrecking balls certainly fit the bill. But there is something compelling about the imagery, the pop-star sexuality, the power of the wrecking ball, the absurd in-your-face quality of the girl licking the sledge hammer, in combination with our knowledge that none of this is of Luise’s making, that it’s all utterly inauthentic, fabricated for a specific effect — that Luise is not the agent but the victim of the video, and that Ferdinand’s reaction is, if anything, even more scripted than the film, and worse in its scriptedness because he’s unaware of just how predetermined his response is. The video and its effects thus engage in a complex play of authenticity and inauthenticity that makes the use of Miley Cyrus anything but arbitrary, given how thoroughly that pop star and her shifting public personae have been analysed in precisely those terms in recent months: Luise is forced to act inauthentically, triggering actions on Ferdinand’s part that feel to him as if they spring spontaneously from his heart, his most deep-seated and authentic feelings — even as they are produced by inauthenticity, take an innocent victim as their target, and conform to easily recognizable stereotypes of masculine behaviour. Far from cooly analyzing the situation, though, Solberg finds visceral forms for the argument, as we get to watch Ferdinand re-victimize Luise, forcing her to sit and swing on the wrecking ball, dousing her in Coke (which, as we may guess, having read the play, is poisoned), and covering her in fire extinguisher spray. She may be on the ball, but there’s no question who is being wrecked in this scene.

Visually and logically, the scene is all about accretion, as Luise’s body is covered in more and more layers of different substances — the soiled white underwear she wears and red body paint from earlier scenes, her sweat, the Coke, the white foam; and as the stage itself becomes a chaos of things, ripped cardboard boxes, spatters of body paint, bags and bags of feathers, gold confetti, water, Coke, spray foam, ping pong balls, and corpses — first Luise’s, then, after a long stagger through all the detritus, Ferdinand’s as well. If Walter in this version presides not over a state, but over a business empire, a president of materialism rather than ducal power, the destruction he causes is also the disintegration of stuff: his scheming kills people, but it also shreds the very world of objects in and on which his power thrives. But as this is not an idealistic production, the tearing apart of people and things does not lead to a better world. The final tableau is ambiguous: the masses now climbing the set may be revolutionaries or the rising forces of a resurgent capitalism. The flags they wave are red and white Nazi flags, but instead of the swastika, they carry the Deutsche Bank symbol. And as Wurm turns into Napoleon, Solberg seems to signal that revolutionary cries for freedom more often than not just produce different types of tyranny — just as Ferdinand’s desire to be free of parental control leads to him exerting the most vicious, lethal control over his lover.

In that sense, this Kabale und Liebe is considerably more pessimistic than Schiller’s, with a Lady Milford whose revolutionary gesture remains without consequence and with a President von Walter whose final gesture of remorse is meaningless. But despite its aesthetics, and despite its ultimate political defeatism, this is a production that again and again finds poignancy in Schiller’s words, and clearly takes a great deal of interest in the language of the play (even as it cuts much of the extraordinarily wordiness of the text). Given the evident and often overwhelming visual and physical qualities of Solberg’s work, this might be an odd point to dwell and end on, but it’s the thing that most impressed me, and what I continue to think of as the greatest difference between German and Anglophone stage work: the ability of German actors to speak lines that are clearly from a different time and from different social registers than those portrayed on stage as if their characters had no other words to say, as if those strange words obviously belonged in those scenes; and to then turn on a dime to either throw in a completely contemporary line, a phrase that couldn’t be from Schiller (or could it?), to switch into dialect or colloquial diction — again, as if that’s obviously what their characters would do. It helps, of course, that the entire show is made up of deliberately artificial elements. The 18th-century language and Schiller’s specific idiom are just another aspect of this artifice. But curiously, the effect of this accretion of artificial tropes, images, and lines is not alienation or even distance, at least not for me. As Ferdinand and Luise were dying, I, sentimental fool that I am, shed a tear or two. There was nothing contrived about that moment, as contrived as everything about it may have been. And that, to me, is what remains truly remarkable about German theatre now: that it does everything to foreground its made-ness, its distance from reality, its absolute and irreducible theatricality — and that in spite or because of that, it manages to find a way of producing a powerfully affective staged reality within and through that uncompromising commitment to the theatrical.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.