Well-Read Plays II

As promised in Part I of this series, here are a few examples of printed plays that have been annotated in a way that suggests the reader had performance of one kind or another in mind. (As before, all images courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, DC.)

First off, a curio. In this copy of the anonymous No-body, and Some-body (1606; STC 18597), someone added a substantial number of stage directions — but virtually all of them concern only music.

This one calls for a flourish (a direction that recurs a couple of times in the volume), and elsewhere a “senate” (i.e., sennet) is added. It’s not likely that a copy as clean as this volume otherwise is would have been a playhouse musician’s cue script (though it’s also not impossible), but we’re certainly dealing with a reader here who approached this text from a theatrical perspective, not a primarily literary one — and from a theatrical perspective that included formal musical signals as a key part of the experience.

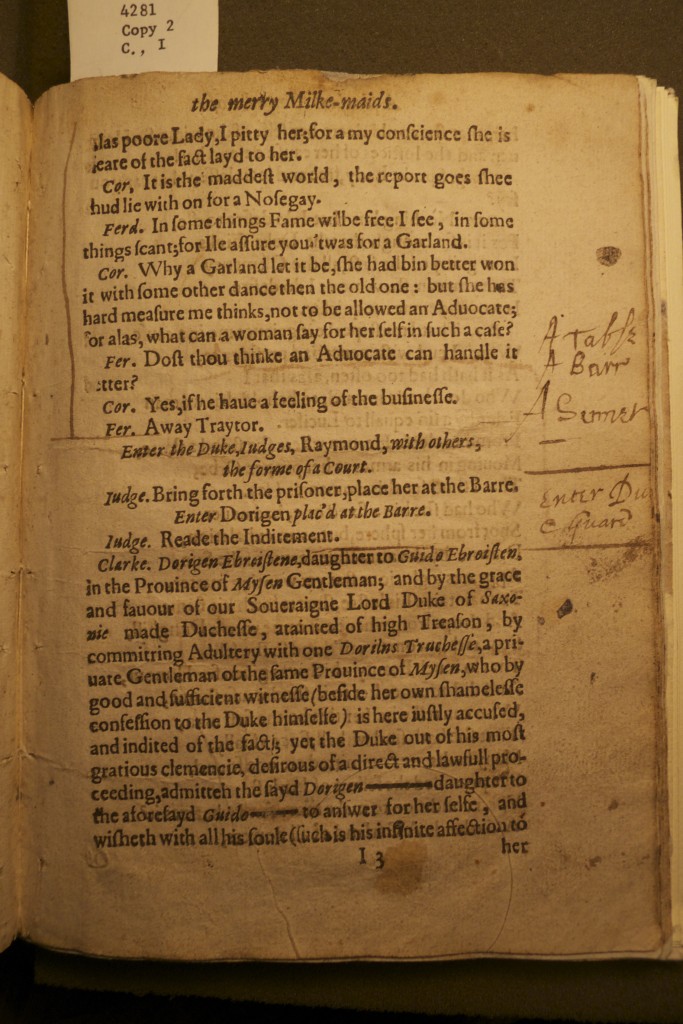

A much better known example of a printed play evidently used as a 17th-century performance text is the 1620 Two Merry Milkmaids (by “J. C.;” STC 4281). This volume was described in depth by my colleague Leslie Thomson fifteen years ago (in “A Quarto ‘Marked for Performance’: Evidence of What?” Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England 8 [1996]: 176-210), and I can’t add much here to her analysis. The images also sort of say it all: this was clearly a well-used book.

Note that the annotations in the first picture (sig. I2v) direct the back-stage personnel to “ready” the items that will be needed shortly thereafter (on sig. I3r): a sennet (i.e., a musician’s performance), a bar (to signify a courtroom), and a table. On the next page, the sennet is called for, and the two props are now required.

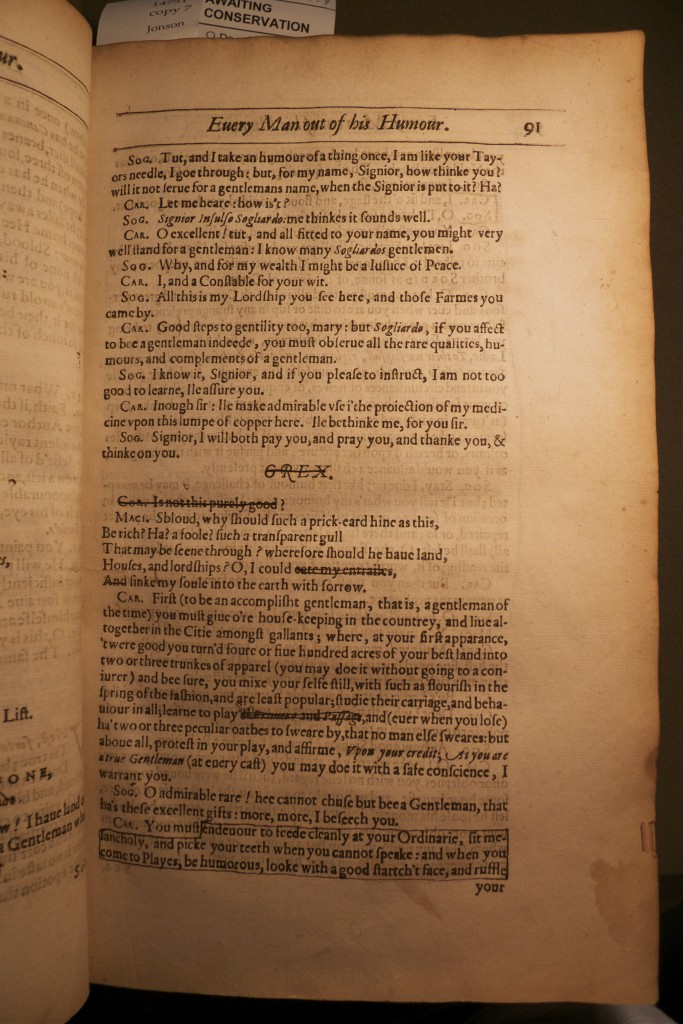

Less well known (as far as I have been able to ascertain), but also less clearly dateable, are performance-related notes in one of the Folger’s many copies of Ben Jonson’s 1616 Workes (STC 14751) — a monumental, beautifully produced, and expensive book that must have made for an awkward back-stage object. And yet, someone went through the text of Every Man Out of His Humour in this copy with a vicious pen, cutting and slashing large chunks of dialogue (including practically the entirety of Jonson’s hugely entertaining chorus of theatre theoreticians).

Cutting the “Grex” may be understandable (although as someone who has played one of them on stage I can’t help but find the decision rash and ill-considered). But losing Macilente’s hilarious “I could eat my entrails” while keeping the rather less impressive “and sink my soul into the earth”? That’s just bad dramaturgy. Changing Jonson’s “O god, god, god, god. &c.” to “O torment! torment!,” on the other hand, was probably a justifiable attempt to avoid an oath (more examples of that in a later post). Personally, I find it amusing that Jonson, despite his reputation for being the most controlling of playwrights, hands over control to the actor here with a casual “&c.,” while his annotator produces a much more specific script.

When those notes were written is uncertain — the hand still uses a secretary “e,” but not consistently (it’s there in the first “torment,” but not the second). I would guess that these are the notes of a mid-18th-century would-be dramaturge.

Finally, here are two examples of books that weren’t exactly marked up for performance, but may have a stronger connection to the playhouse than most.

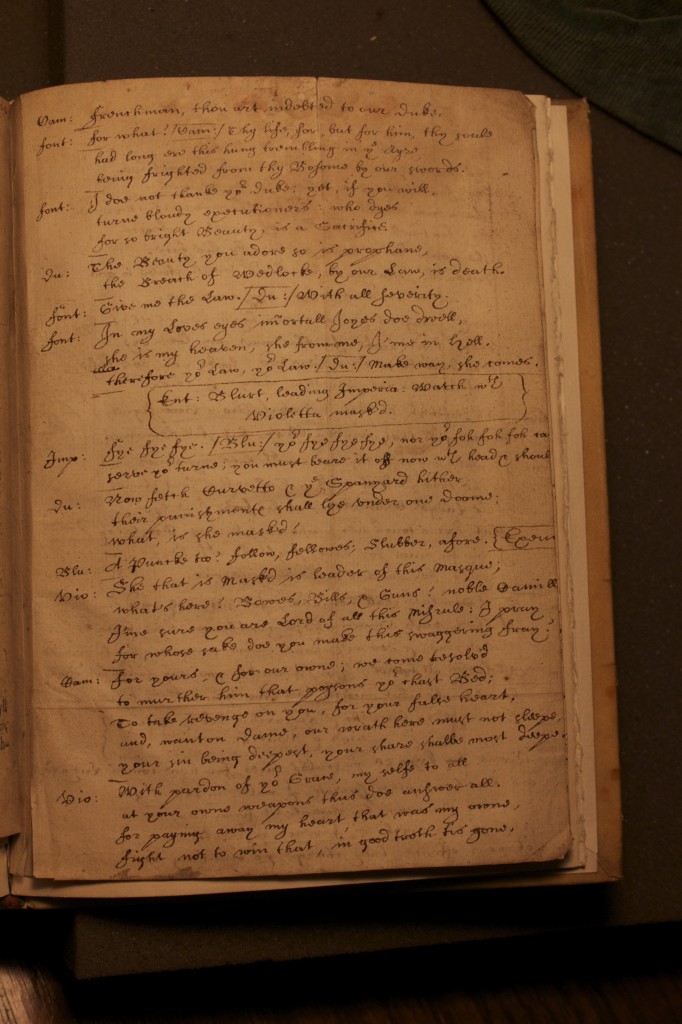

The Folger’s copy of Thomas Dekker’s 1602 Blurt Master-Constable (STC 17876) is missing the final pages, which have been supplied in manuscript. That’s rare enough to be worthy of notice, but in this particular instance, the scribe who produced the substitute sheets clearly had theatrical experience of some sort: formally, his pages look a lot like a playhouse manuscript, and not at all like a printed play.

This may or may not mean that the handwritten sheets are based on a theatrical document, rather than on another copy of the quarto. The scribe who produced them can be linked to other dramatic texts, including a full manuscript of Thomas Heywood’s Dick of Devonshire (he may have specialized in copying oddly-titled plays), but to the extent that his work can be dated, he seems to have been active in the 1620s and 30s — decades after Dekker’s play was published. (A number of scholars have written about this scribe, starting with James G. McManaway, “Latin Title-Page Mottoes as a Clue to Dramatic Authorship,” The Library 4th ser. 26 [1945]: 28-36; see also Akihiro Yamada, “The Seventeenth-Century Manuscript Leaves of Chapman’s May-Day, 1611,” The Library 6th ser. 2 [1980]: 61-9; and H. R. Woodhuysen, Sir Philip Sidney and the Circulation of Manuscripts, 1558-1640 [Oxford, 1996], 143.)

All this raises a couple of intriguing questions: were there still spare copies of Blurt Master-Constable floating around Paul’s Churchyard over 20 years after its first (and only) publication? If so, why was it cheaper to pay a scribe to copy those sheets? Surely an old and apparently unpopular playbook must have been inexpensive? More broadly, why would anyone in the 1620s care enough about this play to seek out both another copy of the book (whether through a stationer or privately) and a scribe to supply the missing sheets — why not just throw out the incomplete text? And lastly, if the manuscript does indeed derive from a theatrical source, and not from another printed copy — and there are enough variants to make this a fairly likely scenario — what does that say about the popularity of Dekker’s play on stage? Blurt Master-Constable was originally performed by the Children of Paul’s, who were long gone by the time this scribe set to work, but it’s entirely possible that the play was later revived by an adult company. A revival might explain both why the text was available, and why the owner of the incomplete book might have wanted to read and own the entire script.

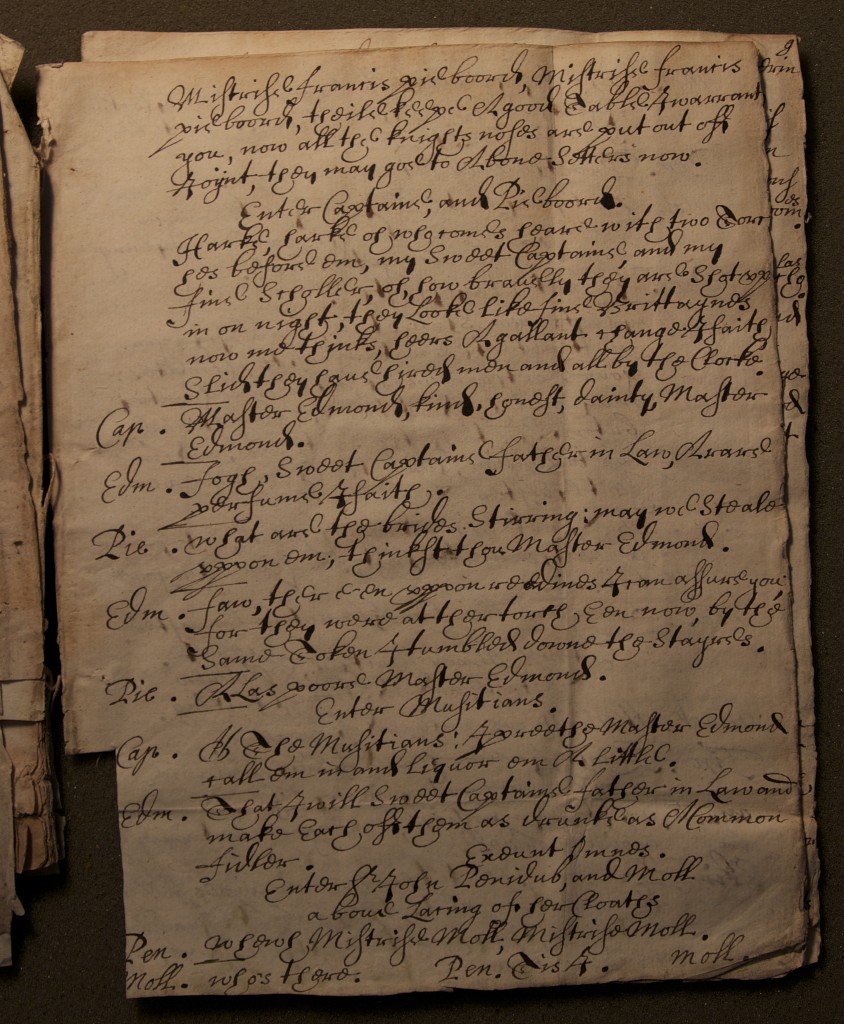

Many of the same questions could be asked of one of the Folger’s copies of Thomas Middleton’s The Puritan (STC 21531) of 1607. This is an even more imperfect copy than Blurt — it lacks all printed matter after sig. G3, with the exception of one leaf, H (which may come from another copy altogether). Here the missing pages are also supplied in manuscript, but the scribe who produced them shows none of the familiarity with playhouse conventions so evident in the previous book. His work essentially reproduces the shape of a printed play:

The formatting of stage directions is the clearest indication: unlike the other scribe, who used the theatrical convention of boxed directions, this one integrates them into the text — confusingly so, as there is no clear difference between lines of dialogue and entrance directions.

In some ways, though, this copy of The Puritan is a more coherent document: it follows the same formatting style throughout, across its two different media. But I find the inserted sheet (H) puzzling. On the one hand, the insertion seems to suggest that the authority of the printed page trumped that of the scribal copy (further increasing, perhaps, the likelihood that the scribal pages are in fact copied from a printed book, and not from a manuscript source). On the other hand, it makes for a visually and materially more unstable, more incoherent book than a straightforward substitution of manuscript sheets for the missing pages would have produced. And again, as with Blurt, the owner’s motivation remains mysterious: why make up a hybrid like this at all, presumably years after The Puritan made its first appearance in print?

One answer might be that the play was included in the 1664 folio of Shakespeare’s plays — it might suddenly have become a more desirable commodity. The scribe’s hand is certainly 17th-century, and the manuscript pages may postdate the third folio. But if the owner was motivated by the text’s newly elevated status, the copy text chosen for the scribe doesn’t make much sense: comparing the copied pages to the 1607 quarto and the 1664 text, it’s clear that the scribe used the quarto, not the folio.

In more ways than one, the Folger Blurt and Puritan are more different than alike, then — but they have one thing in common: they were both first staged by the Boys of Paul’s. Hm….

Next: People who read their plays in totally undramatic ways.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.