Well-Read Plays I

Here’s the first in a series of posts on a long-term research project I’m working on. The project as a whole asks what a printed play was in early modern England — why anyone would have thought turning performance scripts into books was a good idea in the first place, how those books evolved over time into something other than either printed scripts or records of performance events, and how readers approached these texts.

Among other things, I’m looking at the kinds of annotations early modern readers left in plays. And in order to build a truly representative account, I’m trying to produce a comprehensive database of such annotations in as many books in as many libraries as possible. It’s already become clear that such a catalogue will be a useful resource that should be made separately and publicly available online, so that’s now part of the project as well.

A couple of weeks ago, I started work on the database in earnest at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, DC, with the help of three fantastically dedicated research assistants, Tony Antoniades, Joel Rodgers, and Jackie Wylde. The Folger has recently adopted a new and wonderfully liberal digital photography policy, which made it possible for us to take images of manuscript annotations in well over 500 dramatic texts, over half the Folger’s entire collection. It’ll take me a while to take stock of what we have — there are thousands of photographs to review and analyze — but I thought I’d share some examples here. In line with the library’s policies, all the pictures here appear courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library. Comments and responses to these materials would be most welcome!

* * *

As in most early books, the vast majority of readers’ marks and annotations in the plays we have looked at are fairly inscrutable — ticks, little crosses and “x”s, underlinings. Quite a few books feature inscriptions like this one (from Chapman’s 1599 A Humorous Day’s Mirth, STC 4987): efforts by the reader to mimic, fairly mindlessly, the form of the printed text.

(In this particular volume, by the way, you can also see the punch marks that show that this book was previously bound differently — probably in a collection with other playbooks or non-dramatic texts of a similar size.)

A lot of plays contain scribbles that have no apparent connection whatsoever to the text (again, this is true of most books of the period). Some of those scribbles are more interesting than others. Take this feeble, if hard-won, attempt at wit (from the fly-leaf of Samuel Daniel’s 1607 Certain Small Workes, STC 6240):

What the reader (possibly Robert Wynne, whose signatures appears multiple times) tried out, in various hands, and with various false starts, is this piece of inspired doggerel (modernized):

Many men’s swans do swim in the sea, and so do thine with mine;

Many men lie with other men’s wives, and so do I with thine.

Zing!

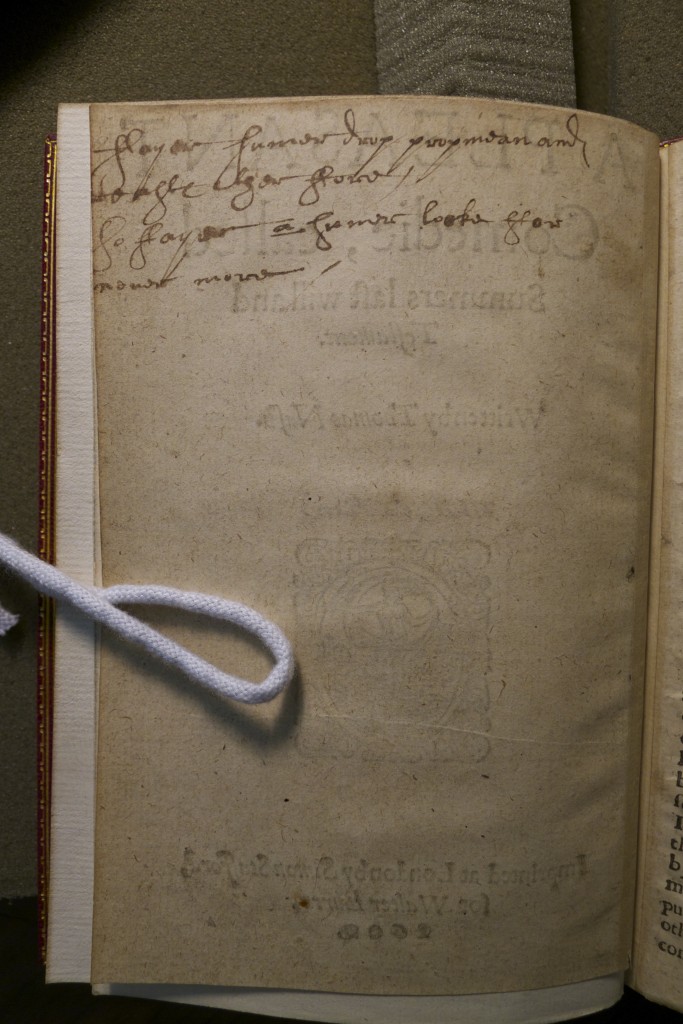

It’s also not unusual to find readers copying out lines from the text, either in the margins or elsewhere in the book. But even though the original was obviously ready to hand, these transcriptions often aren’t models of accuracy. Take this excerpt from Thomas Nashe’s 1600 Summer’s Last Will and Testament (STC 18376):

I’d transcribe that as

ffayer sumer drop prop mean and

beasts ther ffore/

so ffayer a sumer looke ffor

neuer more/

The corresponding lines in the play appear just a few pages later (sig. B2v):

Fayre Summer droops, droope men and beasts therefore:

So fayre a summer looke for neuer more.

Even when copying directly, following the spelling of the printed text clearly didn’t matter to this reader at all, though line breaks did matter. Turning “droop” into “drop” and “men” into “mean” — well, that’s just early modern orthographic creativity. But how did the second “droop” become “prop?” What did the reader think he (or she) was writing — and what did she think she was reading?

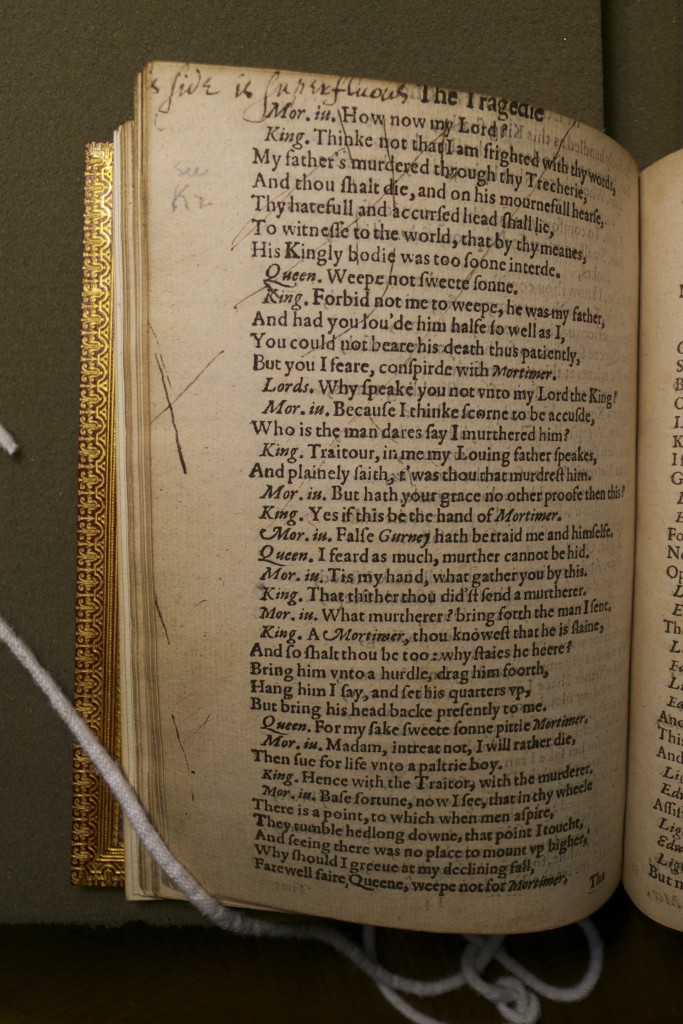

As my last example, here’s a page from the 1612 third quarto of Marlowe’s Edward II (STC 17439):

Here we’re dealing with a full-fledged critic, writing probably later in the seventeenth century. Earlier in the text, this reader had simply crossed out entire passages; on this page (sig K1v), the suggested cuts are accompanied by an explicit judgement: “[thi]s side is superfluous.” The reader doesn’t seem to mean that the page was printed twice — the suggestion appears to be that the entire page should be cut from the text of the play. It’s hard to see how Edward II would work dramatically or narratively without this passage, though — it contains young Edward III’s condemnation of Mortimer, including the failure of Mortimer’s ploy involving an ambiguously phrased kill order in Latin. How is any of that unnecessary for the action of the play? Would the reader simply have preferred it if the young king had dispatched Mortimer more swiftly and more arbitrarily?

** EDIT **

As Martin Wiggins points out in the comments below, I couldn’t be wronger. The page is, in fact, superfluous — it’s a compositor’s error corrected in some copies of the book (STC 17439.5). This reader’s intervention is not that of a critic, objecting to the passage on aesthetic grounds, but that of a reader-editor, making the text less confusing and easier to read. Other readers modified their printed plays in similar ways, as I’ll illustrate in one of the next instalments of this series.

** EDIT **

The OTHER cuts in this copy of Edward II may just possibly be performance-related, but it’s not likely — they’re too sporadic for that. Other volumes in the Folger were more clearly marked up for performance; I’ll write about some of those in part II.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

5 Responses to Well-Read Plays I

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.

[…] he provides a novel piece of research, say, a new analysis of one of Shakespeare’s plays, or even digital images of marginalia from the early 17th century, he can get comments, that is to say, peer reviews, immediately. Indeed, that is precisely what […]

Ha! Thanks for this, Martin. I’d say this is precisely the kind of correction/comment I had been hoping for, except in this case I should have known better myself. (Checking Greg really isn’t too much to ask….)

The EEBO copy is in the corrected state (it’s from the BL), which threw me off — if I had actually checked our spreadsheet, I would have seen what the image itself also should have told me, that this is I4v, not K1v.

So, this now becomes an example of a reader intervening to make the copy more readable. I have plenty of other illustrations of that, for a later post, though I’m almost more intrigued by copies that weren’t corrected, even in books that came with errata sheets. I’ll make a note of this one, though: the ESTC records seven copies of this state, and none of the catalogue entries (except for the Folger’s) mentions annotations (but then hardly any of them record such things). Did other readers also mark up their copies in this way? If they’re all marked up in this way, is this in fact not a reader’s note at all, but the printer’s (unlikely, but who knows)?

I’m putting together a post of Shakespeare-related notes. I haven’t found anything as naughty as yours, though it’s certainly intriguing to see the beginnings of Bardolatry in the annotations of 19th-century readers who are clearly going through other authors’ plays primarily to identify parallels to and echoes of Shakespeare’s works.

The important point about the Edward II example is that this *is* a duplicated page. It’s actually I4v, not K1v (as you can see from the show-through at the bottom) and in some copies the text there is the same as on K2r. (The error was corrected during the print run. Greg offers a detailed and plausible explanation of how it happened in his entry on the play: Bibliography of English Printed Drama, i. 214.) That is evidently what the second annotator understood the note and deletion to mean: ‘see K2’ is added in pencil. The other cuts may well be interesting in a literary rather than a primarily bibliographical way, though this one does also show how early book owners intervened to deal with deficiencies in copies (like the handwritten addition of Troilus and Cressida to the list of titles in some copies of the First Folio).

If you do find anything along the lines of what Julian Munds suggests, please make sure you set your forgery detectors to maximum! I vividly remember being excited in the Bodleian for about 30 seconds upon finding a – non-dramatic – Elizabethan quarto annotated with something like ‘King John poisoned by a monk. Good idea for a play. W. Shakespeare.’ It was, of course, a naughty eighteenth-century owner of the book, messing about.

Fascinating. I am doing a study of reading texts in theatres – 18th century so later than your focus. Sometimes done to catch actors out. Many actors report dreading the sight of audience members with the text in their hands.

That was very interesting. Perhaps one day you’ll find a scribble that says “Going to kill Marlowe tonight for being a spy,” or “Saw today large Dark Lady with William Shakespeare, I think her name was Mary Fitton.”