Wednesday, 8 January 1919

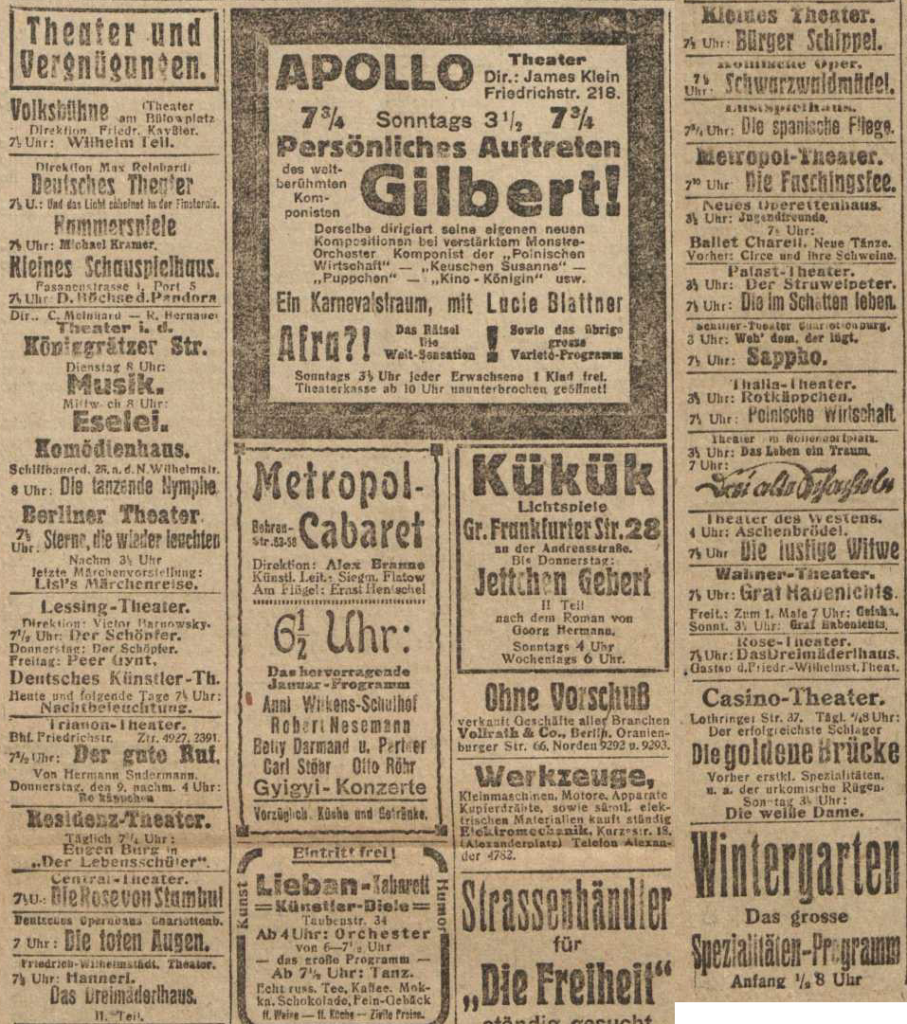

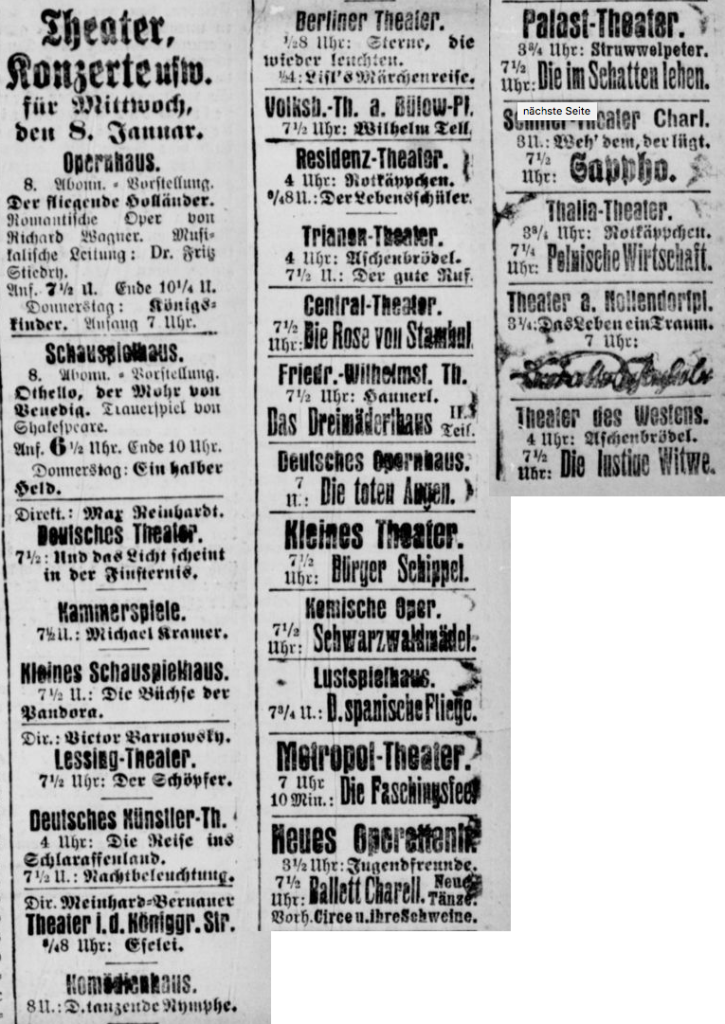

The situation in Berlin remained chaotic: the police had ceased to operate, armed units of government forces and of revolutionaries could be seen all over the city, and public transport had ground to a standstill. Exactly who had the most popular support was a matter of debate: the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung portrays a Berlin under the yoke of “Spartacist terror,” with a government hiding behind “a well of ‘faithful’ soldiers, armed to the teeth” and a citizenry seeking refuge behind “safely barred apartment doors”: the streets are “governed by Spartacus.” Freiheit, on the other hand, as a publication ideologically aligned with the workers and their various representatives (including the Spartacists), uses streets filled with people engaged in “lively debates,” with complicated dividing lines: well-dressed citizens arguing for swift and brutal military intervention, being cheered by some of the workers; soldiers arguing against a military solution, winning over the worker-dominated audience again, and so on. Armed government troops were being applauded loudly in the street — by the bourgeoisie. But others, opposed to a return to “the old ways” express their support for the workers. In other words: Berlin remained in turmoil. And as on Monday and Tuesday, the theatres remained unaffected by any of it. Their programs show no sign of disruption. Freiheit, though, still doesn’t have an add from the State Opera or the State Theatre, so I’ll give you two sets of listings again; first, from Freiheit:

Second, from the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung:

We have classics! The Volksbühne put on Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell — a play that later this year, when Leopold Jessner directed it at the Staatstheater, would cause one of the biggest theatre-political scandals of the century. And the Staatstheater staged Othello. I’ll talk about this one in some detail below.

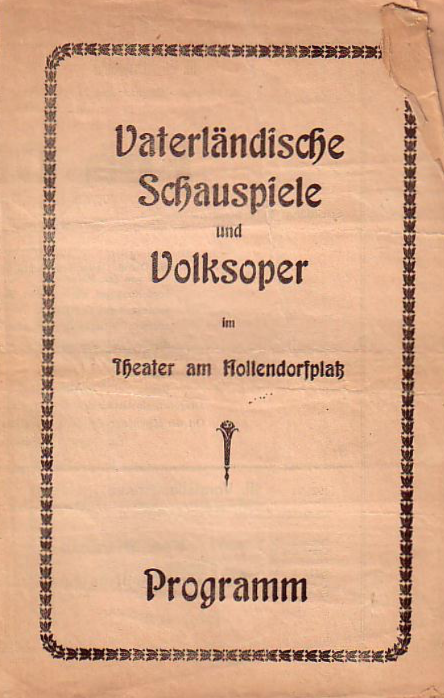

What else is worth noting? Lots of afternoon performances. A number of theatres are offering “fairy tale shows”: “Lisl’s Märchenreise” at the Berliner Theater, “Aschenbrödl” (Cinderella) at the Trianon-Theater and the Theater des Westens, “Rotkäppchen” (Little Red Riding Hood) at the Residenztheater and the Thalia Theater, “Struwwelpeter” at the Palast-Theater, “Die Reise ins Schlaraffenland” (The Journey to the Land of Cockaigne) at the Palast-Theater. I presume these were meant for children. And there’s another set of matinees, which may have been intended for (and marketed to) high-school students: productions of classics, quite likely plays that were part of the high school curriculum. The Schiller-Theater in Charlottenburg staged Grillparzer’s 1838 comedy Weh dem der lügt; the Theater am Nollendorfplatz a play called “Das Leben ein Traum” — either another Grillparzer, his 1834 Der Traum ein Leben or Calderón de la Barca’s 1635 Life is a Dream. The Theater am Nollendorfplatz regularly hosted such production, as the dramaturg Hans-J. Weitz later recalled in a memoir of his first encounters with the theatre: they were produced by an association called the Vaterländischen Schauspiele — in this context, something like “the patriotic acting company” — which aimed to give students at institutions of learning “a lively impression of classical drama;” ticket sales were organized by high-school teachers. Once Weitz, then thirteen years old, had seen his first “real” show, though, Reinhardt’s Minna von Barnhelm at the Deutsche Theater, in 1918, he proudly declared “I’m never going to the Nollendorf-Theater again!” Established in 1914 and increasingly a means of providing work for actors who had become unemployed during the war, the organization continued into the early 1920s, staging plays as well as operas; here’s a cover of one their programs from November 1920:

Other things: a bit I missed yesterday. “Kater Lampe” at the Staatstheater on January 7 was a folk play, in Saxon dialect, by Emil Rosenow — and another Rosenow play was also on stage at the Palast-Theater on January 6, and is back today (after The Mikado took its place yesterday!): Die im Schatten leben (“The Shadow-Dwellers”). Perhaps innocuous enough, probably a coincidence, but I wonder how this play would have read during those days of political turmoil: a tragedy set among coal miners in the Ruhr valley, written by a dramatist who also was a Social Democratic member of Parliament until his early death in 1904. It’s certainly somewhat edgier fare than I would have expected in a theatre seemingly specializing in popular entertainment and light opera!

The award for creepiest title goes to Die toten Augen (“The Dead Eyes”) at the Deutsche Opernhaus in Charlottenburg, a turn-of-the-century opera by Eugen d’Albert, first performed in 1916. There is a modern recording!

Now, for that Staatstheater Othello. It was a new production that season, having premiered on 5 December 1918, and would remain in the repertory for two more seasons, with an ultimate total of 53 performances. In the 1921/22 season, it was replaced with Leopold Jessner’s Othello, a staging widely hailed, at the time and since, as a high point of Weimar theatre — but Jessner’s version only ran for two years, being performed just 35 times! The older staging, directed by Reinhard Bruck (one of the two interim directors of the State Theatre), with sets by Hans Kautsky and Fritz Mach, and costumes by Robert Franck, was an altogether less distinguished production, redolent everywhere of this theatre’s old, courtly, pre-revolutionary aesthetics (Herbert Ihering, one of the period’s most important critics, would soon decry those aesthetics as “Mr Kautsky’s decorative hodgepodge”). The program in fact list four designers, noting that “furniture and props” were built based on “drawings by theatre painter Eugen Quaglio” — it was precisely this attention to decorative detail that Jessner’s regime would sweep away come the end of 1919. Quaglio was the last scion of a family of theatre painters stretching back generations; he lived until 1942, but his employment at the State Theatre ended in 1923. He must have realized that he had already become something like a historical figure at that point: he offered to sell his family’s collection of sketches and drawings to the Munich Theatre Museum when he retired, and the museum hosted an exhibition about his and his family’s work that same year. (See Christine Hübner, Simon Quaglio: Theatermalerei und Bühnenbild in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts [Berlin, 2016], 138-39.) Quaglio’s art was the pictorialism of a bygone era, a visual embodiment of the State Theatre’s reactionary, royalist heritage; here’s what his art (in a landscape painting rather than a set design) looked like:

That the show nevertheless marked a transition point is clear from the reviews. Its premiere was the first in the Staatstheater after the end of the monarchy on November 9, as Fritz Engel, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt, notes: “So, not ‘royal’ anymore! A few draperies, embroidered with the crown, have disappeared, almost all the eagles [of the royal crest] have been covered in gauze, and in the great royal box, for which tickets can now be bought, a single man sits, looking abashed.” Engel senses hints of a longed-for change in the production, an impression of a directorial “temperament,” even though on the whole, he finds the evening incoherent, a blend between “old theatre” and the attempt at a more contemporary mode of performance. The Social Democratic party newspaper, Vorwärts, sees a similar tension: the venue, so “sophisticated and ceremonial” hasn’t changed, except the royal “stucco nonsense” has vanished (metaphorically, not literally: the Nazis would actually strip out the Wilhelminian stucco almost third years later); on stage, “one senses something of the new spirit, the shaking-off of the old shackles and a delight in the new-found freedom.” But the “comfortable seats” are still occupied by the “old regulars” — “for now,” at least. And the Berliner Volkszeitung is sure that the production was put on with precisely those regulars in mind: the audience that had “remained faithful to this theatre even in these revolutionary days” deserved an Othello at “their” theatre to rival the stagings of the play Reinhardt had directed at his venues in previous seasons (and which remained in rep in 1918).

Even so, or for that very reason, the Volkszeitung sees Bruck’s direction as a clear break with the Staatstheater’s established style of “mis-en-scène, which has to be regarded as a superannuated court-theatre tradition, dominated by pageantry in every aspect,” seeking instead to come closer to a true “Shakespearean spirit” in “simplifying and humanizing” his approach. But as vague as that statement is, it is also the most detailed any of the reviews get in assessing what the production or its director actually tried to do. (For good reason, probably: Ihering later described Bruck as a weak director, devoid of a sense of space or an idea what to do with actors’ bodies, obvious in his interpretative angles and superficial in his stylistic choices; “the best that could be said of his direction is that it avoid kitsch, but it does not move beyond it.” Hardly a figure to lead the Staatstheater into a new era.) Mostly, the critics describe one thing: the performance of Theodor Becker in the title role.

Becker had only recently joined the ensemble of the Staatstheater, having established a stellar reputation in Dresden before. (In its casting, the production was literally a mix of old and new: Becker, the newcomer, delivering a kind of Othello not seen before on this stage, on the one hand — and, in a smaller role, Agnes Straub, destined to become one of Berlin’s most admired actors, playing an Emilia described as “boundary-crossing,” “surprisingly original,” even “disquieting”; but also as “doing too much” and a “busybody.” On the other hand, the veteran Alfred Kraußneck’s Brabantio was literally imported from an earlier staging: as the Volkszeitung remarks, without obvious disparagement, “Kraußneck’s Brabantio is well familiar from the past.”) If the December 1918 reviews are anything to go by, his Othello was a star turn. But if it seemed strikingly modern, that modernity — a modernity grounded in an avoidance of “old-fashioned pathos” and a focus on a “psychological, interior working-through of the jealousy issue,” an Othello reluctant to act violently, whose “injustices and cruelties are merely the forced actions of a deeply confused soul” — would very soon seem terribly old fashioned, an approach long practiced on other Berlin stages, and soon outmoded by young directors combining a sense of political urgency with a focus on “re-theatricalizing” the stage. But for a brief moment, Becker’s star shone very brightly: Fritz Engel thought his performance a “precious achievement” and felt certain that “it would not be forgotten.” Becker, he prophesied, was destined to be “Matkowsky’s heir” — the successor of the State Theatre’s legendary actor of heroic parts, its iconic Coriolanus and Othello, a huge figure, physically and otherwise, excessive onstage and off, who had died young just ten years earlier. A slightly strange claim, this, given Engel’s description of the performance: not at all physically expansive or expressively outsized, on the contrary, almost “child-like” — Othello as a “good child, that is awoken from a sweet dream and becomes furious,” a “moor” “credulously in love with his happy fate” in the first act, a man who “wants to keep dreaming on,” and hesitant to allow Iago to rob him of his calm. His fury, later, is “more like a convulsion, flashing through him briefly without quite subjugating entirely” — a “lyrical” Othello, a “pious” one, who “acts out his revenger’s office as a terrible necessity.” (Alfred Klaar likewise thought what was powerfully affecting in the performance was Othello’s “enormous pain” rather than his “wildness.”) There was one moment, though, that reminded other reviewers of Matkowsky as well: when Othello, suddenly furious, jumps on Iago, grabs him by the throat, and demands proof — a moment that, to one critic’s mind, illustrated a fury “beyond all European measure.”

Most of the critics, as much as they would like to see the Staatstheater awoken from its court-theatre stupor, seem to see in Becker a return to past glory, under somewhat different performative parameters (a Matkowsky informed by Naturalism and psychology, perhaps). That’s not the tenor of the Vorwärts review, though: the change that reviewer has in mind is clearly rather more of a real departure. His response to Becker’s performance is correspondingly tepid: admiring his power, his ability to “think through and give a shape” to his role and the play as a whole, he still sees in him an heir to a reactionary tradition: “He has the affectations of the grand court-theatre style, his delivery rolls and hisses, he thunders loudly. One would hope for more mid-range, more shading.”

The left-most critic seems to have had it right. Becker did not last. Three years later, he was gone, unable to adjust to the new tasks set for him by a new generation of directors — widely criticized, in fact, as an almost singularly catastrophic failure in Leopold Jessner’s epochal, pathbreaking opening production on the same stage almost exactly a year after his seemingly career-making Othello.

Perhaps oddly, about the Othello, I can say no more: nothing specific about the sets, nothing about the text, nothing about anything, really, other than Becker’s performance; the fact that it ran for almost four hours; that Becker wore light brown make-up, “Moorish” (“Maure”) not “Negro” (“Neger”) — most reviews of most Othellos, until not too long ago, include this kind of racist categorizing; and the critical consensus that most other actors faded to irrelevance. If photos of the production exist, I have not seen them. But I wonder how quickly its initial promise faded. If in December 1918, the hope for a recovery through some sort of restoration still seemed plausible, how disconnected from reality would that hope have felt on 8 January 1919, in a Berlin in the midst of an armed uprising, a clash between different democratic forces that would eventually be resolved through a deeply troubling alliance between Social Democratic and reactionary forces?

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.