Tuesday, 7 January 1919

Berlin remained in turmoil: the editorial in the morning edition of the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung called it “open war of citizens against citizens” and describes the scene: “Public life has slowed to a trickle, shops and banks are closing, vehicles are unable to pass the clogged-up streets, the barrels of machine guns are looming from windows and gates.” That’s the left column of the paper’s front page. On the right, the theatre announcements paint a very different picture: show after show, listed in orderly fashion, with no disruption in sight. Juxtaposing the BZZ ads with those in the Independent Social Democratic Freiheit again, though, there seem to be differences, though, possibly defined by class or ideological divides: the State Opera and the State Theatre always advertise in the more middle-class (more bürgerlich) newspaper, but not in Freiheit (they did on January 6, but not on the 7th); cabarets only advertise in the left-wing publication.

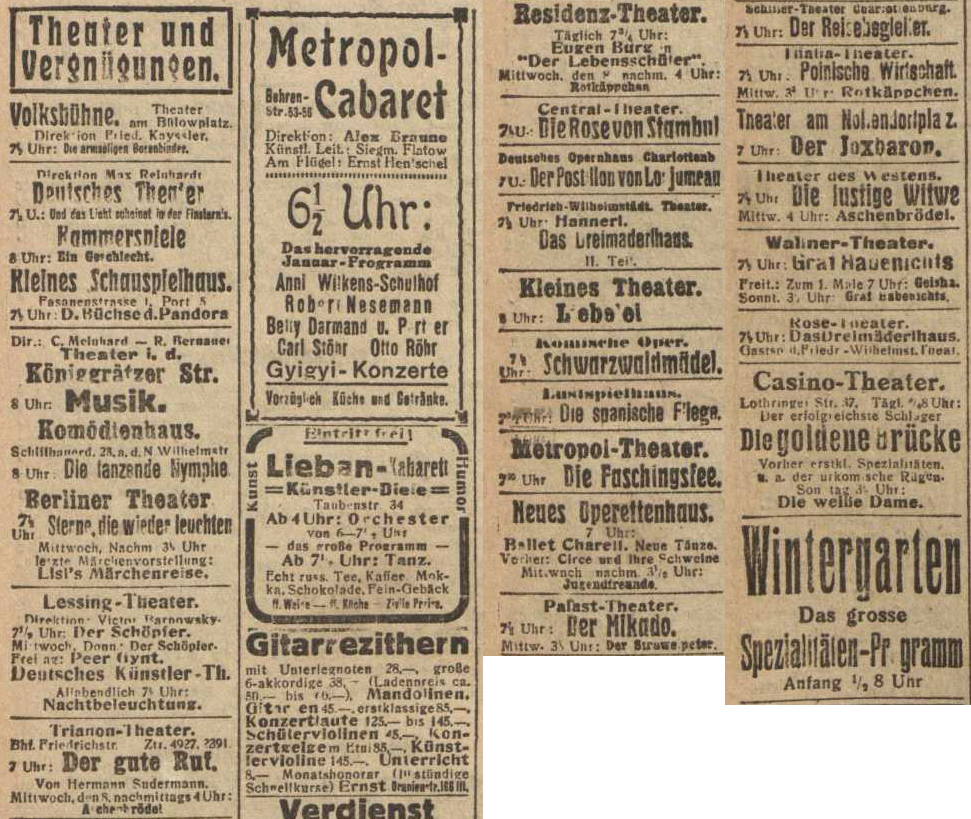

Here’s the theatre and entertainment section from Freiheit:

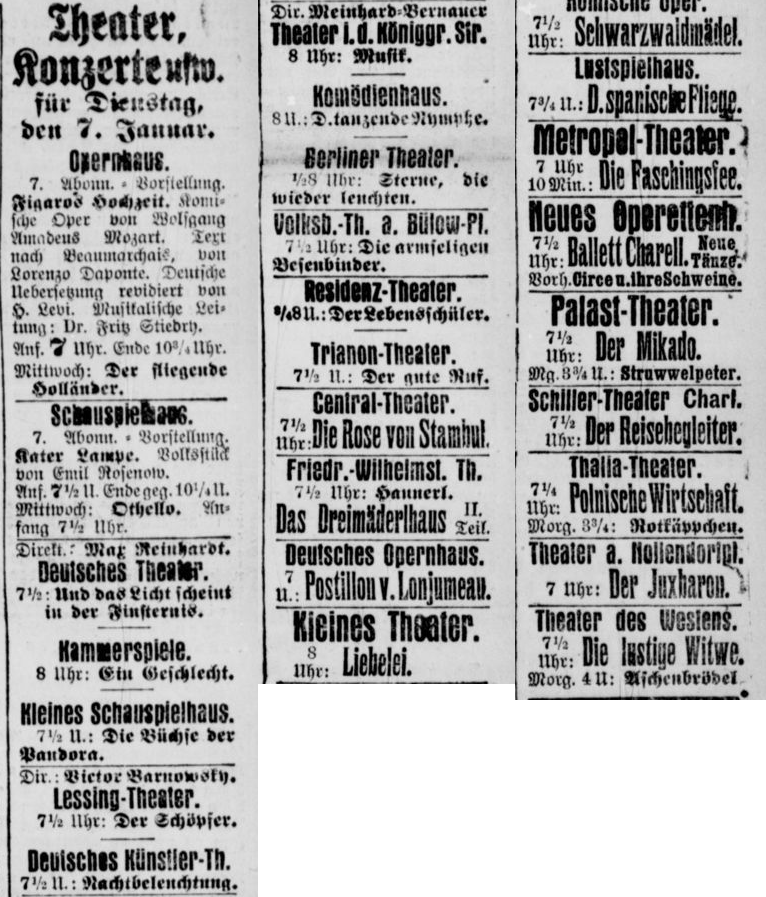

And here are the front-page ads from the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung:

One trend may already be visible if we compare today’s listings with yesterday’s: some venues run shows en bloc, others operate on a true repertory system. Operas don’t seem to be performed night-after-night anywhere — the State Opera is following yesterday’s Carmen with Figaro’s Hochzeit and is announcing tomorrow’s Fliegenden Holländer, the Deutsche Openhaus, where Der Freischütz played yesterday, is now staging Adolphe Adam’s Le Postillon de Lonjumeau (not an opera I was familiar with, but apparently it remains in the repertoire). Reinhardt’s theatres — the Deutsche Theater, the Kammerspiele next door, and the Kleine Schauspielhaus — operate on a system of short runs (we’ll see this over the next few days); only one of the three has a different show on today from yesterday. The same is true of the Volksbühne. The State Theatre changes over daily: today, they’re offering a folk play, written in dialect, as forgotten now as yesterday’s Ein halber Held: Emil Rosenow’s Kater Lame. Theatres specializing in popular entertainment aim for long runs — we’ll see how rarely venues such as the Lustpielhaus, the Central-Theater, or the Trianon-Theater change their programming. Victor Barnowsky again deserves special mention: his Lessing-Theater was trying to run a repertory-based program rich in new and recent “serious” plays; similarly, the “Kleines Theater,” which he took over from Reinhardt in 1905, continued to operate on that model after Barnowsky moved on to the Lessing-Theater in 1913 (a word more about this theatre in a minute).

Any noteworthy plays or productions this day? Fritz von Unruh’s Ein Geschlecht at the Kammerspiele is, sort of. The play was first staged by the private theatre club Reinhardt initiated in 1917 to allow for the production of cutting-edge new drama despite war-time censorship restrictions, the “Das Junge Deutschland” (“Young Germany”). Those productions were only ever put on as matinees. Once theatrical censorship ended with the collapse of the monarchy in November 1918 such work-arounds were no longer necessary, yet the Young Germany scheme continued until 1920 — but only two shows produced under censorship conditions were ever transferred to the regular repertory. Ein Geschlecht was one of those, and the performance on January 7 was its evening premiere (it would only see 7 more performances).

Also worth noting: how prominent Wedekind’s plays were in those years. Der Marquis von Keith at the Lessing-Theater, Die Büchse der Pandora at Reinhardt’s Kleinem Schauspielhaus, Musik at the Theater in der Königgrätzer Strasse (where the play had been running since 13 December 1918).

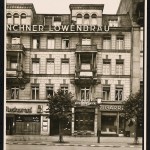

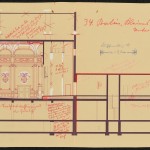

Finally, the promised word about the Kleine Theater: the tiny theatre that could. It was Reinhardt’s first stage in Berlin, it’s where he became famous, made a set of new, young actors famous, and launched the careers of playwrights — it’s also the theatre where Oscar Wilde’s Salome was first performed in Germany and where Gorky’s Lower Depths became a sensation in January 1903 (mere weeks after its Moscow premiere). within a year of Reinhardt taking over, Alfred Kerr, Berlin’s leading critic, called it “the noblest place” for the fostering of new dramatic developments. And it remained a key venue for new drama for decades, despite its extreme physical limitations. In a speech in 1930, the critic, dramaturg, and director Felix Hollaender recalled its unlikely emergence: “soon all of Berlin flocked to the uncomfortable, cold auditorium he unpretentiously calls the ‘Little Theatre.’ This rather bleak room, whose stage was more like a pastry board, was where the future of the Deutsche Theater was born.” “All of Berlin” would have been difficult to accommodate: the Kleine Theater had fewer than 400 seats; its stage really was little more than a cutting board, a mere 80 square metres; and it had no technical equipment to speak of (and would not acquire any, ever). Given Reinhardt’s later fame for technical wizardry, it’s intriguing to think that he rose to fame as a director on Berlin’s smallest and most limited stage.

-

- The entrance to the Kleine Theater (at that point renamed “Theater under den Linden”) — dwarfed by Löwenbräu and Cigars! (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 026, 8)

-

- Kleines Theater, floorplan — fairly rudimentary and without measurements. The stage is the small patch in the lower left quadrant. (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 026, 4)

-

- Side elevation of the Kleines Theater, showing the minimal size of the stage and the small auditorium. It may look as though there’s a rear stage: there wasn’t. (Compare the floor plan.) This was annotated in the early 1940s by an exasperated Third Reich functionary tasked with assembling data about all German theatres; querying the point of a small red box at the edge of the stage, he scribbled: “What is this strange item? A prompter’s box, in which the poor man has to sit with his legs folded beneath him, while his head still ends up sticking out high above the edge??!” (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 026, 5)

Liebelei, the Schnitzler play on offer there on 7 January 1919, was not new (it had premiered 20 years earlier in Vienna) and without the kind of digging that would take me too far off my current research’s path, I can’t say anything about this particular production. But it might be worth noting that of all the plays on stage in Berlin that day, it is pretty much the only one that remains in the modern German repertory. It had its most prominent recent — well, sort of recent — production at the Thalia Theater in Hamburg in 2002, directed by Michael Thalheimer, and invited to the 2003 Theatertreffen.

No video online, sadly, but here’s an intriguing video montage of the actors’ faces (in true 2002-YouTube-quality) that was used in the show:

Edit: I knew I had seen a clip from the production! Here it is, starting at 0:37:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Die Berliner Volksbühne: Ein Zentrum für politisches und experimentelles Theater - Kunst 101 on What’s so special about German theatre: Part 1

- My Homepage on Shakespearean Mythbusting I: The Fantasy of the Unsurpassed Vocabulary

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.