The Strange Case of Thomas Dekker

[This is a very lightly edited version of a paper I gave last weekend at the Renaissance Society of America conference in Washington, DC. Many thanks to Adam Hooks and András Kiséry for organizing the panel and for their excellent papers!]

Thomas Dekker should be central to discussions of early modern theatre, but he isn’t. He should occupy a prominent place in discussions of the development of a market for printed drama, but he doesn’t. He should be a key character in accounts of the rise of the professional author, but he isn’t. In this post, I will provide something of a basis for these claims about Dekker’s importance, and will try to explain why he has proven such an elusive figure.

Dekker in the Theatre

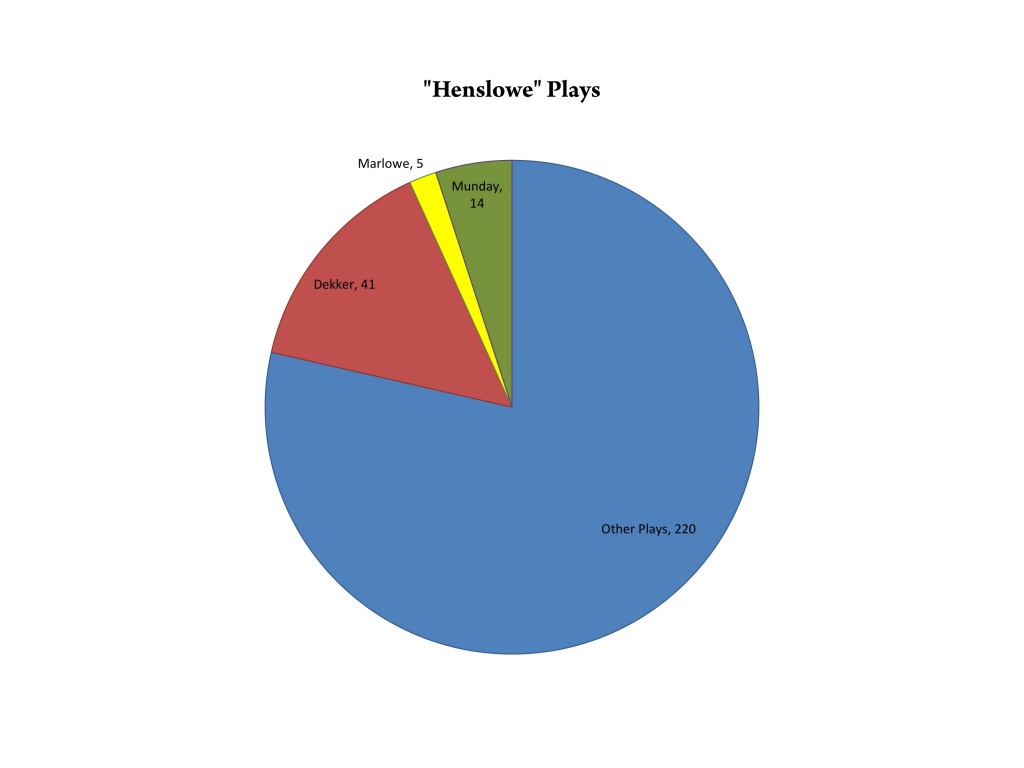

One could make a strong case for Dekker as the hardest-working playwright of his generation. In Henslowe’s diary, only Henry Chettle is associated with more plays than him, and unlike Chettle, Dekker worked for Henslowe without a single recorded break over the six years the “diary” covers, 1597-1603. Dekker earned over £100 in those years, more than twice as much as the next most productive writers, Drayton and Haughton. He was involved in the writing of 41 new plays (besides providing additions for revivals), 11 of which seem to have been entirely his own work. And besides producing works for the companies at the Rose and Fortune theatres, in the same years he also worked for the Chamberlain’s Men (for whom he wrote Satiromastix in 1601) and for the Children of Paul’s, who also staged Satiromastix, and for whom Dekker wrote Blurt Master Constable in 1601 or 1602.

Unlike other dramatist who have been described as central to the Henslowe’s companies’ repertory, especially the Admiral’s Men, Dekker really did produce a very significant proportion of the 280 or so plays listed, in one form or another, in Henslowe’s records. Marlowe, the usual suspect, was responsible for just 1.8% of those plays. Munday, more prominently, wrote 5%. Dekker, on the other hand, contributed to or wrote almost 15% of the known Henslowe repertory.

Unfortunately, we can’t say precisely how popular Dekker’s plays were on stage – once Henslowe begins to record payments to writers he promptly stops recording takings on a per-performance basis. The best we can say is that the Rose does not seem to have attracted smaller audiences in the years of Dekker’s prominence. If anything, by 1598/99, his most productive year, it looks as if the Admiral’s Men were on something of a rebound. (The figure for 1597/98 almost certainly reflects a change in Henslowe’s bookkeeping method, not an actual precipitous drop in takings.)

The fact that the company turned to Dekker and his regular collaborators – Chettle, Day, Haughton, and the others – again and again also suggests that the plays they wrote were popular with audiences. And it has to be significant that both the Admiral’s Men’s court performances in the 1599/1600 season were of Dekker plays – Old Fortunatus and The Shoemaker’s Holiday.

Dekker in Print

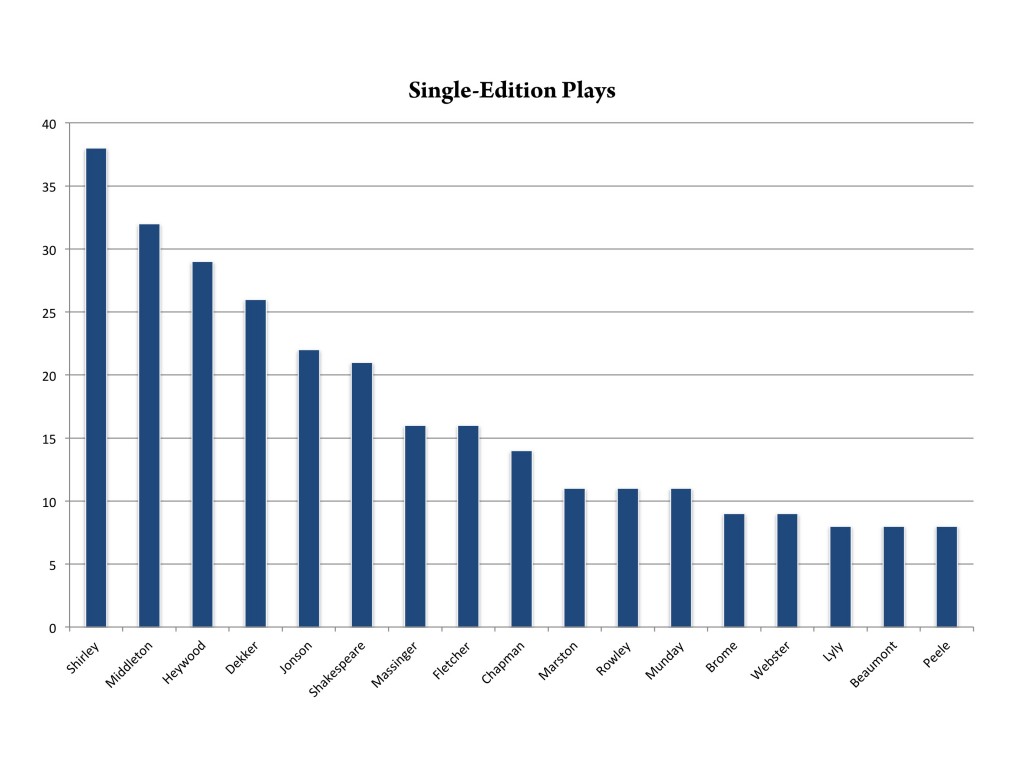

The prominence of Dekker’s works, and of plays he co-authored, in the Henslowe records did not immediately translate into similar prominence in Paul’s churchyard. But over the course of his long career, a significant proportion of his dramatic output did appear in print, making Dekker the fourth-most published playwright of the period.

Limiting our count to works written for the professional stage bumps him up a place, behind only Shirley and Heywood, on par with Middleton and Shakespeare, ahead of Fletcher and Massinger, and well ahead of Ben Jonson:

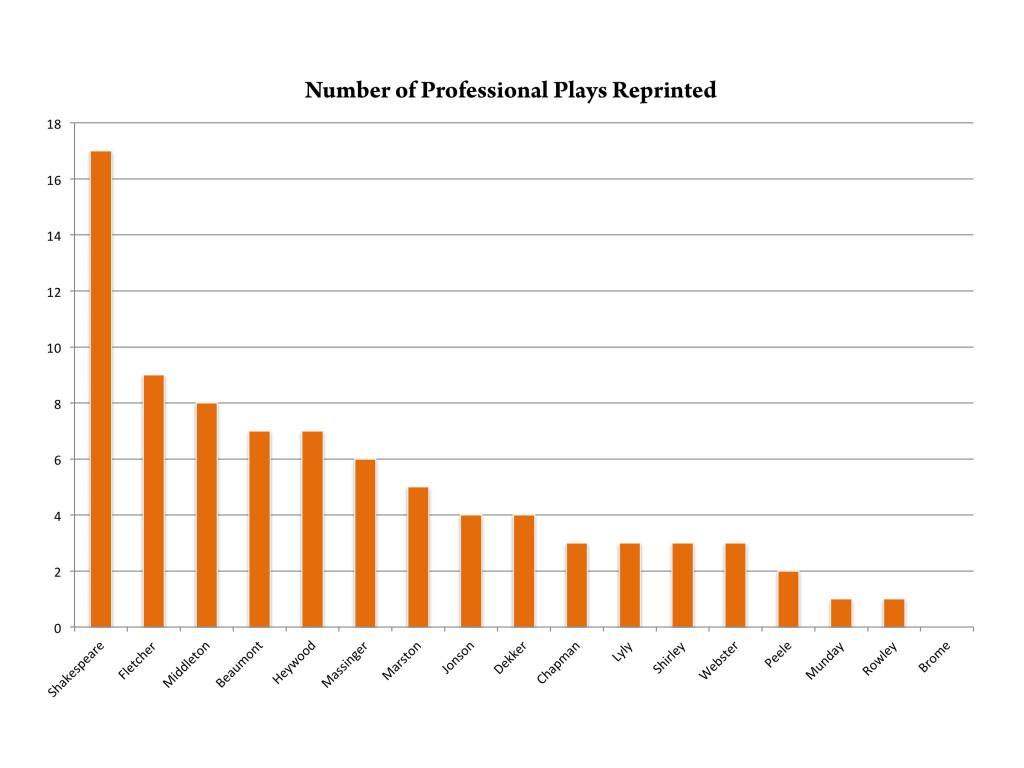

However, if reprint rates are indeed as reliable as a measure of success as scholars have assumed in recent years, Dekker loses some lustre:

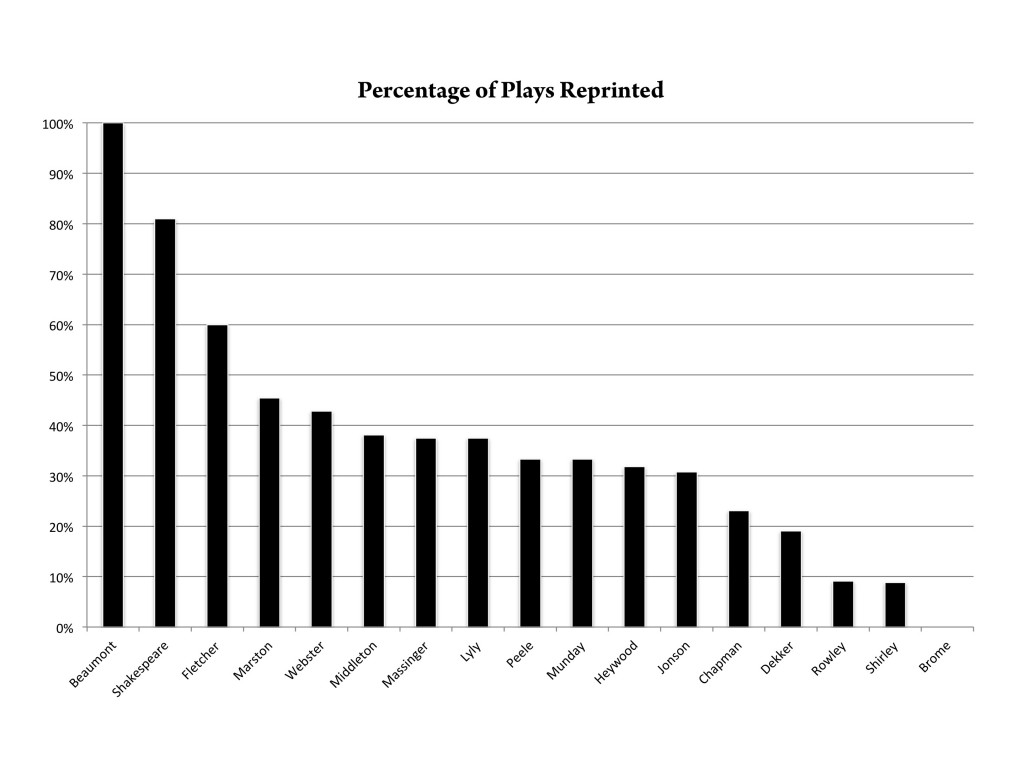

Only four of his many plays saw further editions, leaving him trailing Middleton, Beaumont, and many others – above all Shakespeare, as Lukas Erne has recently documented in some detail (my figures here are very rough, counting all reprints before 1660 and not taking into account how quickly books were reissued, and discriminating against titles first issued close to my cut-off date). Worse, only a very low percentage of Dekker’s plays were reprinted: just 19%, which puts him near the bottom of our list:

This lack of popular appeal is surprising, especially given how often stationers seemed to be willing to invest in the publication of one of his plays. Two of them did sell very well: Shoemaker’s Holiday with 6 and the first part of The Honest Whore with 5 editions both are among the 20 best-selling playbooks of the period. But that can hardly have been the key motivation for any stationer to take a chance on a Dekker play.

The comparison with Jonson, on the other hand, may be more instructive. Jonson’s plays also were rarely reprinted – the single quarto of Epicene followed the play’s publication in the folio and Catiline had a curious revival in 1635. But other than that, only two of his dramatic works seem to have been popular in print, and both share the same unusual publication history: Every Man Out of His Humour and Eastward Ho both were reprinted twice the same year they were originally published, and never again thereafter. Both bursts of popularity were fuelled by scandal, and may have taken stationers by surprise: the quick successive reprints at least suggest the possibility that neither William Holme nor William Aspley and Thomas Thorpe expected much from the books and kept the initial print-runs small.

This is not the place to try to trace the multiple transfers of rights in Jonson’s works between stationers; there is no question that his publication history is a good deal more complicated than Dekker’s, if only because the latter never attempted to gather his writings into a single volume. But the two writers do have something in common: both had plays printed in unusual numbers despite the fact that neither showed great potential for best-selling success. In Jonson’s case, some scholars, most prominently Zack Lesser, have argued that certain stationers, such as Walter Burre, sought to associate themselves with a certain kind of literary prestige while banking on the moderate financial success of a single sold-out edition. No one, as far as I know, has attempted to make a similar case for Dekker’s plays.

I’m not about to try anything of that nature either, but it is worth pointing out that in 1598, the same year Dekker first shows up in Henslowe’s diary, Francis Meres included him among the dramatists “best for tragedy” alongside Kyd, Marlow, Chapman, Ben Jonson, and Shakespeare. Not only does this imply that he was anything but a novice by the time Henslowe starts recording payments to dramatists, it also puts Dekker in fairly impressive company – company that would succeed in establishing plays as both valuable and popular print commodities and as a form of literature. What is more, two years after Meres’ Palladis Tamia, quotations from Old Fortunatus and unidentified other works find their way into Robert Allott’s England’s Parnassus (1600), where they are attributed to Dekker but without the play’s title. Allott includes more excerpts from Dekker (18) than from Jonson, and almost none from Marlowe’s dramatic writings. In fact, the only playwrights more frequently cited than Dekker are Robert Greene (21) and Shakespeare (30). Together with the Admiral’s Men’s decision to feature his works so prominently in their court performances of 1599/1600, these references may indicate a relatively widespread perception of Dekker as more than a mere playhouse hack.

The Invisible Dekker

Let me now turn to a single case-study to illustrate further that Dekker’s works may have had a more pervasive and more long-lasting influence – or at least appeal – than his checkered publication history may seem to indicate. It’s an appropriately local piece of evidence, from the holdings of the Folger: a copy of Blurt, Master Constable, published by the amazingly-named Henry Rocket in 1602 and now generally assumed to be by Dekker. (I briefly discussed this volume in a previous post here.)

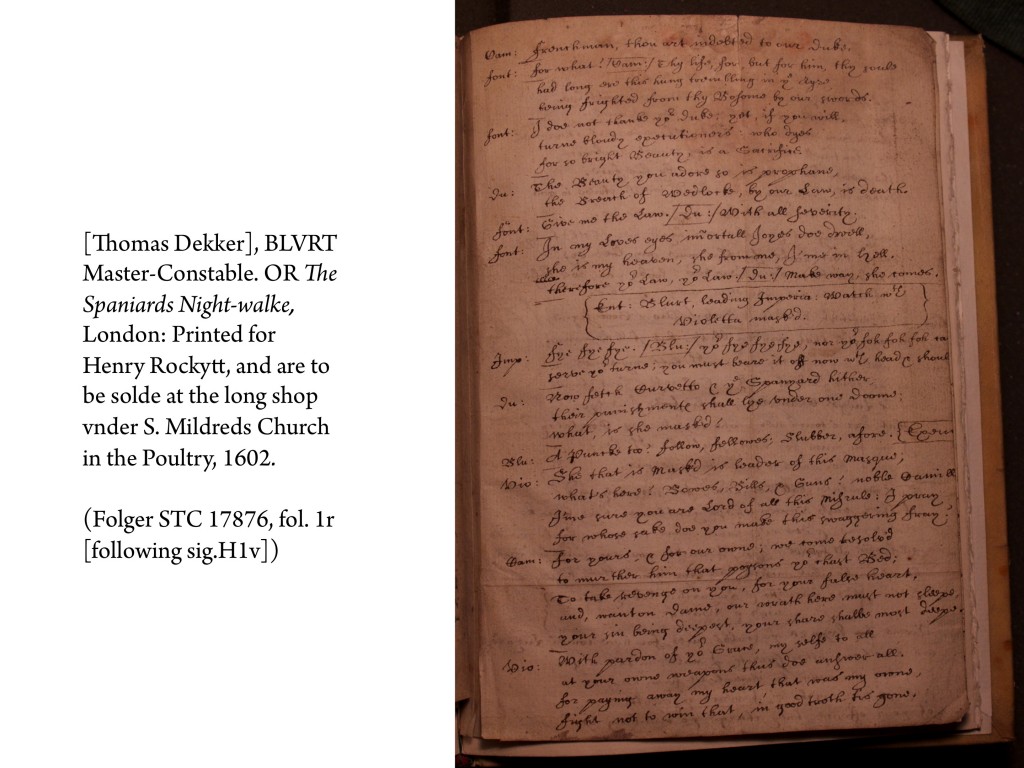

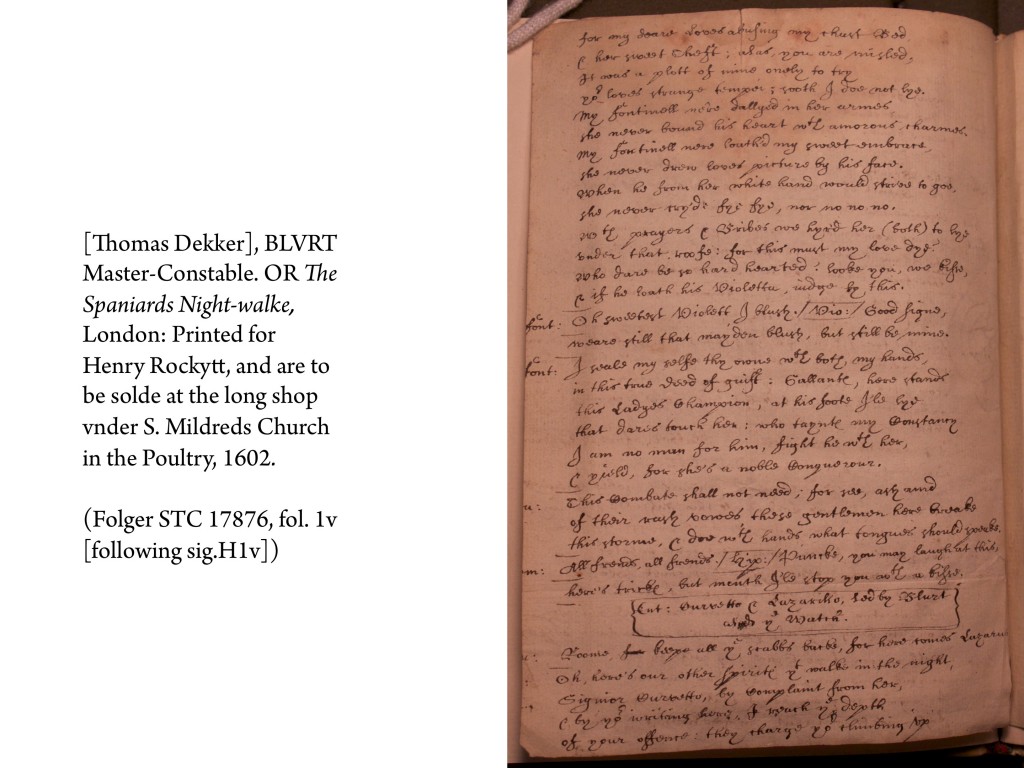

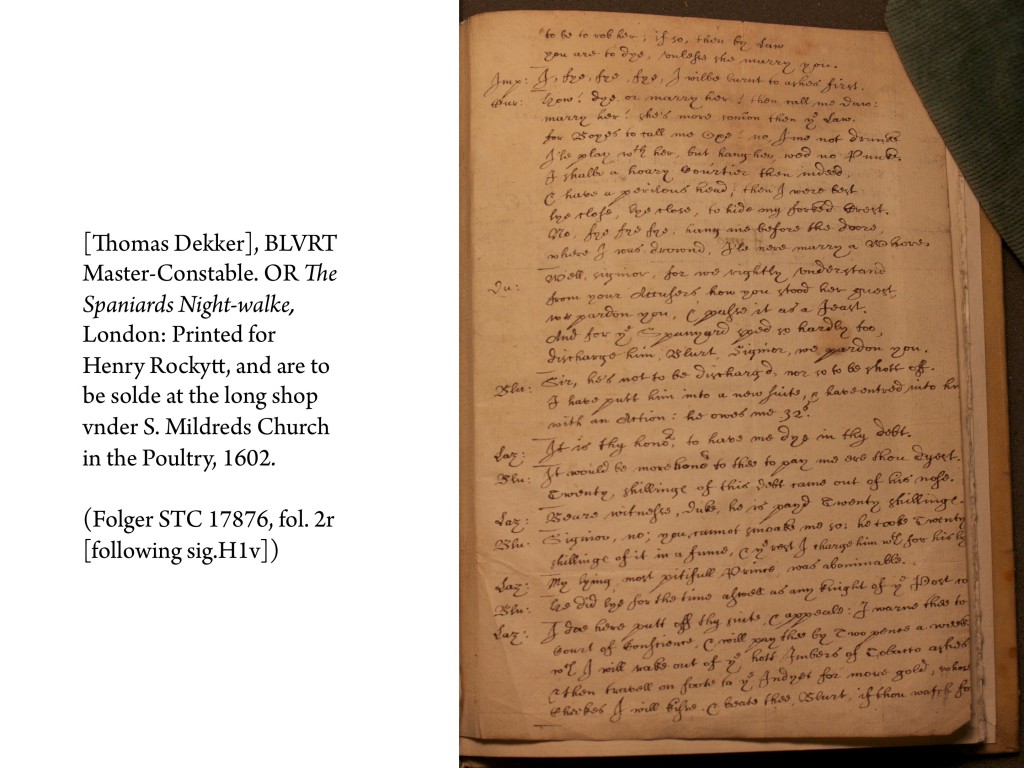

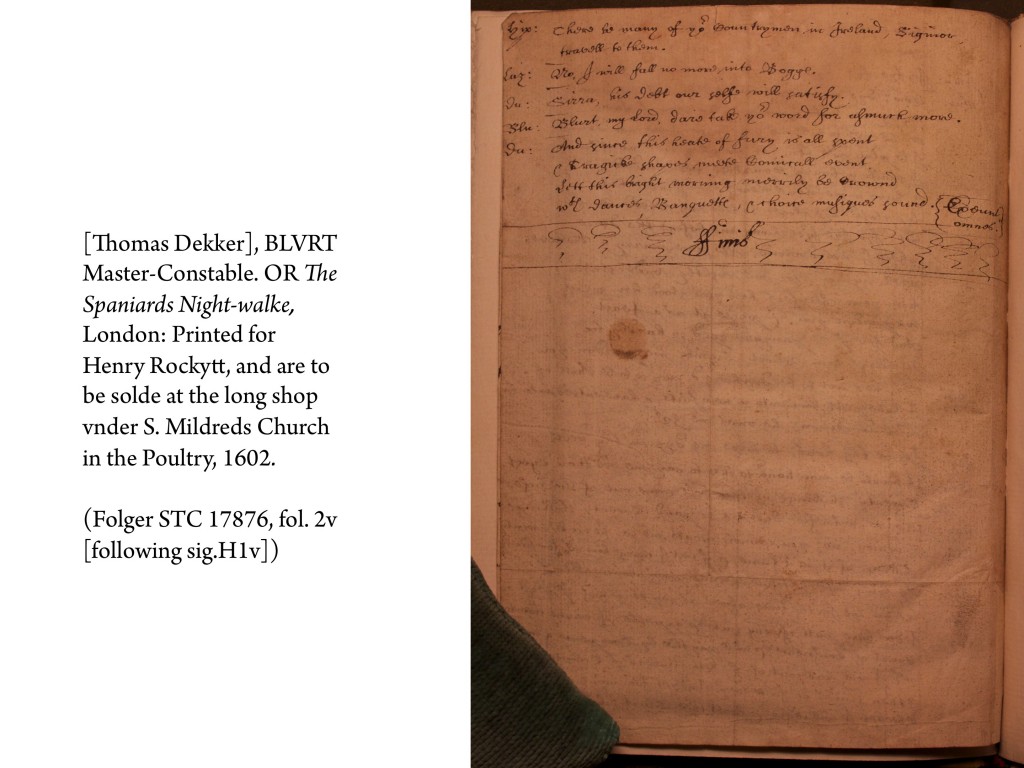

In this volume, all but the first leaf of the final gathering was lost or destroyed at some point between publication and the 1620s; the missing text was supplied in the form of two sheets of manuscript bound together with the remains of the 1602 quarto.

The added sheets are in the hand of a scribe who also produced a number of other literary manuscripts, including the only surviving text of Dick of Devonshire, a play now generally ascribed to Thomas Heywood, the plot of which draws on events that took place in 1625. These documents allow us to date the production of this hybrid volume of Blurt Master Constable with some confidence to the 1620s — decades after Dekker’s play was published. In other words, the owner of this particular copy of the text was keen enough on owning a complete version of an old and obscure work to pay a professional scribe with connections to the theatre to copy out the missing pages, investing about half as much as the price of a new copy of the book (since the going rate for scribal work was a penny-and-a-half per sheet). This scenario raises a host of questions, but for my present purposes, it serves most immediately as an illustration of just how difficult it is to determine popularity based on the fragmentary records we possess.

Let me spell out what I mean. Based on what we know about Dekker’s history in print, we might call the first part of The Honest Whore and The Shoemaker’s Holiday his great successes; we might add Old Fortunatus to that list, on the basis that Allott, an at least in some senses representative reader, drew on that play so liberally for England’s Parnassus. But Blurt Master Constable would most likely find a place among Dekker’s many poorly selling playbooks in our narrative – after all, we only know that it wasn’t reprinted after 1602, and isn’t mentioned anywhere as either influential or current.

What the Folger volume suggests is that a) Dekker’s play still had a keen readership – at least a readership of one – in the 1620s; b) that reader could still access Dekker’s play two decades after its original publication; and that c) it was apparently easier for that reader to procure a manuscript of parts of the play than simply to buy a second printed copy, which seems to suggest that Blurt Master Constable had sold out and was well-liked enough not to be available in the second-hand book market – even though this apparent popularity was not enough to persuade a stationer to reprint the play. Pursuing this final point would lead us deep into the tangles of stationers’ biographies without much hope of enlightenment: after Henry Rocket died in 1611, his wife sold his shop and inventory to the bookseller John Smyth; a few years later, she transferred all of Rocket’s copyrights to Nicholas Bourne (like Rocket, a former apprentice of Cuthbert Burby’s), but the list didn’t include Blurt, Master Constable. Possibly, the rights in the text were simply lost or wound up in the hands of a stationer who had no interest in publishing plays (Bourne was one of them). It is unclear who occupied the “long shop in the Poultry” in the 1620s, and we don’t know what happened to whatever remained of Rocket’s stock. Where then did our anonymous, but keen, reader find his manuscript?

This is where the form of the written sheets provides a clue. What is most remarkable about them is that they look nothing like a printed play, and a lot like a playhouse manuscript. This may or may not mean that they are based on a theatrical original, rather than on another copy of the quarto. As we saw, the scribe who produced them can be linked to other dramatic texts, including a full manuscript of Dick of Devonshire; he also provided a manuscript replacement for the first two leaves of a copy of Chapman’s May Day of 1611 now at Worcester College in Oxford. All three of those documents share the same set of formal features: short lines marking the beginning and end of speeches, speech tags added after the main block of the text was copied, stage directions enclosed in boxes. These were the techniques of the playhouse, not of a compositor. It is certainly possible that this scribe simply copied from printed originals, imposing on them the visual apparatus with which he was familiar. But it seems more likely to me that he was reproducing the features of his originals – that he copied the missing sheets of Blurt, Master Constable and of Chapman’s May Day directly from theatrical manuscripts.

If that is indeed the case, the Folger’s composite book speaks volumes not just about the submerged popularity of Dekker’s play as a text for reading, but also about its popularity on stage. Blurt Master Constable was originally performed by the Children of Paul’s, who were long gone by the time this scribe set to work, but it’s entirely possible – even likely – that the play was later revived by an adult company. A revival would explain both why the text was available, and why the owner of the incomplete book might have wanted to read and own the entire script. The same scenario, incidentally, may apply to Chapman’s play, which was also first staged by a children’s company, the Children of the Chapel.

In neither case do we know anything about the author’s involvement in these potential later revivals. May Day announces its author’s name on its title page, both in the printed original and the manuscript copy at Worcester. But Blurt leaves Dekker out of the picture. The play may have been enduringly or newly popular, but whether such popularity was in any sense connected to the playwright responsible for the text is at least doubtful.

Dekker as Author

As an author-figure, Dekker, is always shifting in and out of focus. Old Fortunatus is an intriguing case in point. The play seems to have been based on an old text (performed previously, as an old play, by the Admiral’s Men in 1596), but Dekker received such generous remuneration for his work on what Henslowe, in 1599, calls “the whole history of fortunatus” that it is generally assumed that Dekker entirely rewrote the work; we know that he almost immediately revised it again, and gave it a new ending, for its court performance. However, despite the generous payments, and the multiple authorial interventions, when the play was printed in 1600, just a few months after its first staging, the performance occasion trumps Dekker’s role: the title page proudly announces Old Fortunatus “as it was plaied before the Queenes Maiestie this Christmas, by the Right Honourable the Earle of Nottingham, Lord high Admirall of England his Seruants,” but doesn’t mention the playwright. (The same is true of Shoemaker’s Holiday). And yet, although on this print occasion, company and royal audience are more important than author, when Allott excerpts the play for England’s Parnassus in the same year, only authorship seems to matter. Dekker, in 1600, was both eminently visible and entirely absent as the author of Old Fortunatus; but he was better paid for his absence.

Dekker’s status as author was further complicated by his frequent collaborations. Again, however, the consequences of this professional choice for his public persona are less than predictable. Whereas Shoemaker’s Holiday, apparently a non-collaborative play, never mentions Dekker’s name in any of its six editions, part one of The Honest Whore, his other frequently reprinted play, mentions only Dekker in all its five editions, despite the fact that the text was co-written by Thomas Middleton (as we know from Henslowe’s diary).

Finally, there is a timeline of sorts to Dekker’s emerging authorship. None of his plays printed in Elizabethan England appeared with his name on the title page (and none of them add it in subsequent editions); all of his Jacobean play-publications name him as author or co-author. But who were the agents behind this development? Stationers presumably played some role, though mediator figures such as Meres and Allott may have been more important. Playing companies obviously could influence what reached print and under what circumstances to some degree, if they so chose (in Dekker’s case, a particularly intriguing instance of a company trying to control the market is the Admiral’s Men’s payment of £2 to an unnamed printer for the staying of the publication of Patient Grissil in March 1600, a Dekker collaboration only completed a few months earlier). Individual playwrights were likely not legally unable to sell their works to stationers after selling a separate copy to a company of players, though the practice was clearly frowned upon (as Thomas Heywood wrote in the preface to his Rape of Lucrece in 1608). More than anything, however, Dekker’s endless work as a collaborator may have made it impossible for him to gain the same kind of prominence in print that he has in the pages of Henslowe’s diary, and for entirely pragmatic reasons. Unless a playing company actively chose to publish a co-authored play, there may simply not have been a play to publish: it is entirely possible that none of the authors ever had a full draft of the entire text. (This, by the way, may make us reconsider why exactly Jonson repeatedly wrote his co-authors out of his published plays: did he perhaps make a virtue out of a necessity?) More frequently a collaborator than not, Dekker’s ability to present himself – literally, to sell himself – as an author in print may well have been strictly circumscribed by the simple fact that he had very few complete plays to sell. Dekker as an author, then, existed in the unified, singular form the term implies, only on the title pages of some books – books that variously suppress or highlight his status as a collaborator. As dominant as he was, he was also remarkably elusive; no wonder we have such trouble putting him at the heart of our theatre – and literary – historical narratives.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

6 Responses to The Strange Case of Thomas Dekker

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

Recent Comments

- Die Berliner Volksbühne: Ein Zentrum für politisches und experimentelles Theater - Kunst 101 on What’s so special about German theatre: Part 1

- My Homepage on Shakespearean Mythbusting I: The Fantasy of the Unsurpassed Vocabulary

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.

Very fascinating and informative.

Excellent work, Holger! I once imagined writing an article called “Drama and Society in the Age of Dekker,” on the grounds that he’s far more characteristic than Jonson, but it never got beyond a few scribbles. As you suggest at the end of your essay, it is precisely because Dekker fits so poorly into the authorial model of most literary history that he is so significant.

Maybe not a home run . . . There is no mention of Dekker’s other writing of rogue literature which is important now. Perhaps it wasn’t important then ? Did those who bought plays also buy pamphlets ? Was authorship important for pamphlet buyers ? Which paid better ?

a 30-yard screamer into the back of the net – bravo Holger!

Thank you, Jonathan! (I’m so used to baseball metaphors now that it took my brain a moment to readjust to football imagery…)

Okay then: home run! You touched all four bases!