An Election Lost and Won

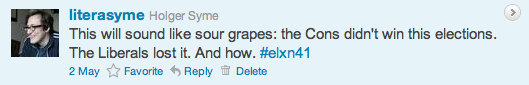

Hours after the election had been called for Stephen Harper’s Conservatives last Monday, I, slightly shellshocked, posted this tweet:

A week later, I would mend the PTSD-induced grammatical shortcomings, but my analysis of the election results hasn’t changed substantially. Let me explain.

A Tale of Two Waves

Depending on how one looks at the outcome of the vote, either everything changed on May 2 or almost nothing at all. There is now a Conservative majority, the NDP are the official opposition, the Liberals have fewer seats than the NDP had in the last parliament, and the Bloc has been reduced to near-irrelevance. Oh, and there’s Elizabeth May. From the perspective of practical consequences in the House of Commons, then, this has been a momentous election.

From the point of view of voter support, however, the shift appears nowhere near as dramatic. Luke Andrews has demonstrated this in a very compelling graphic format here: outside of two provinces (admittedly the most populous ones), things remained pretty much as they had been – some seats changed hands, but that occurs in all elections. And Luke’s cartogram still only tells the story of what happened to seats, if in a geographically specific form.

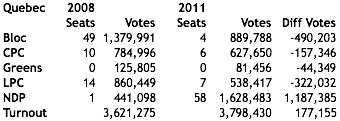

A tabulation of votes, on the other hand, provides a more nuanced picture of how seats were won, and exactly how much the balance of power or of popular support shifted. And here, to anticipate my own argument, two very different stories emerge, even if the resultant pictures, in the cartogram, look surprisingly similar. Expressed in terms of seats, an orange wave rolled over and submerged Quebec, and an analogous dark blue wave took Ontario – more specifically, the Greater Toronto Area – by storm. However, while the NDP did indeed win a massive number of races in Quebec on the basis of a groundswell of unprecedented popular support, the same is not true of the Conservatives in Ontario. Consider the numbers:

This is a truly astonishing result. Not only did the NDP almost quadruple their share of the popular vote, but every other party lost support. All those losses combined with all new voters just about amount to the NDP’s 1.19 million new votes. Interestingly, the Liberals’ share dropped almost as precipitously as the Bloc’s, and they pulled off that most typical of first-past-the-post feats, gaining more seats than their opponents (in this case, the CPC) while winning over fewer voters. That’s what pundits call “efficient.”

On a seat-by-seat basis, this kind of wave has more than just ripple effects. Of their 58 seats, the NDP won 50 with at least 4000 votes more than anyone else, and in many cases with an outright majority. In the entire province, only two seats, Gaspésie – Îles-de-la-Madeleine and Montmagny, could be considered squeakers for the NDP: in the former they won by a mere 800 votes, and the latter remains undecided (since the NDP candidate was ahead of the Conservative incumbent by only 5 votes, the riding is currently in a recount). None of the other parties had victories that comfortable: the Bloc came close to losing even more seats, pulling off a 4000+ vote advantage in only one riding; the Liberals defended 5 of their 7 seats with smaller majorities, and the Tories held on to two of their 6 seats by narrow margins.

By any measure, then, the NDP triumph in Quebec was remarkable. It came as the result of a surge in popular support that largely obliterated differences between ridings and riding-specific issues (including the notorious Vegas-candidate). But we shouldn’t let those local particularities fall entirely by the wayside, as some of them suggest that what may look like province-wide movements can have little or no effect on the constituency level. Take the somewhat paradoxical fate of two Conservative incumbents: on the one hand, there’s Steven Blaney in Lévis – Bellechasse, whose voter supporter increased from 24,785 to 25,810; on the other hand, there’s Jean-Pierre Blackburn in Jonquière – Alma, whose share plummeted from 26,639 to 18,569. Blaney held on to his seat quite comfortably, Blackburn suffered a resounding loss to the NDP’s Claude Patry. Whatever these figures represent, it’s not a provincial trend. Blackburn’s severe drop is no more in line with the Conservative’s overall numbers in Quebec than are Blaney’s gains. So even in a situation where huge shifts in the overall orientation of the voting public tend to outweigh local concerns, the larger trend cannot account for variations (decisive rather than minor in nature) on the riding level.

And this observation leads me to the other wave – the one that seems to have swept through the GTA.

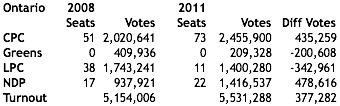

Here are the numbers for Ontario:

The NDP’s gains here weren’t as impressive as in Quebec, but it bears stressing that they still grew their vote by over 50 percent: not exactly an everyday achievement. The Conservatives attracted almost as many new supporters while everyone else lost, though not as dramatically as in the neighbouring province. Without detailed exit polls, it’s hard to argue about voter movements, but it seems at least likely that a greater proportion of former Green voters switched to the NDP, that the Tories picked off a fair number of right-leaning Liberals (more about that below), and that the NDP profited from the increased turnout – though there is no immediate reason to assume that the two winning parties didn’t just split the new voters between them.

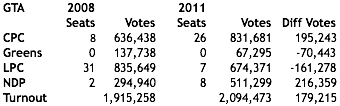

What is so remarkable about the NDP results in Quebec is that the party came from behind in all but one of the ridings they won and still managed to trounce the opposition. This is not quite the case for either the New Democrats or the Tories in Ontario, and in particular in the GTA. Given how much the political landscape in the 416 and the 905 areas appears to have changed, I’ll focus on those ridings here. Overall, the picture in and around Toronto resembles that in the province at large:

As you can see, the Conservatives won 18 of their 22 new Ontario seats in the GTA, while the NDP gained 6 (they lost Sault Ste. Marie to the Tories, a result that deserves further analysis). But how the two parties won those seats is instructive. Over half the new Tory seats, 11, went their way by less than 4,000 votes, six of them by less than a thousand. None of the NDP’s new MPs won by quite such small margins — they range from a majority of 1,289 to a whopping 10,150 (Andrew Cash in Davenport). But the Conservatives also took a few ridings thanks to massive gains, in particular the three Brampton seats. It is much harder to describe the general character of either Conservative or New Democrat wins; unlike the Quebec wave, the sea change in Ontario was a complex development, influenced by specific local factors, and playing out in rather different ways in different places. That said, we can generalize about a few things: on average, the more new voters came out, the worse the Liberals did, and no ridings attracted as many new voters as those with Tory incumbents; the NDP needed far more additional votes to win new seats (7,806 on average) than the Tories (with 4,964); a surprising share of the Conservative vote was concentrated in ridings with Tory incumbents (over 33 percent), which is also where the party could record its greatest improvements (in that sense, the Conservative vote wasn’t quite as “efficient” as pundits have claimed). I would also argue that vote splitting played far less of a role than has been widely suggested – more about that below.

How to summarize the situation in the GTA? In one sense, what happened here is not that dissimilar from the events in Quebec: a major party suffered at least a partial collapse. The Liberal vote was already depleted in 2008, and shrunk further this year. It’s thus perfectly obvious who lost this election: the Grits only grew their share of the popular vote in two GTA ridings, and they lost both of those; even in ridings they managed to hold they dropped over 4,100 voters on average. What is far more difficult to say is who benefitted from this collapse. In Quebec, the votes freed up by the Bloc often had nowhere to go other than the NDP, and new voters opting for other parties were more than outnumbered by people switching to the NDP (so that in effect every new voter in Quebec was a New Democrat). It was the mass shift of all those votes that triggered the tidal wave. In Ontario, that wasn’t the case: voters abandoning the Liberals almost certainly went both right and left, as did new voters. But such movements aren’t large enough to produce landscape-altering surges (even if seat distributions may suggest as much). Adopting a more accurate – if cumbersome – aquatic metaphor, what happened last Monday could be figured as a complicated waterworks, composed of an array of interconnected basins. In individual ridings, the same shifts we can observe on the provincial level can favour different parties, with divergent outcomes (an incumbent carrying on with a smaller share of the vote; a new MP from either challenging party winning the seat). But the underlying balance between the parties hasn’t been fundamentally altered: the system remains in place.

The Myth of the Split Vote

Much has been written about the effect of vote splitting in Ontario. And sure enough, in the most banal sense, the Conservatives benefitted enormously from the fact that there were two viable options on the centre-left this year. Combine the Liberal and NDP vote, and the Tories wouldn’t get much of a look in – even if you deduct a few percent for right-leaning Grits who wouldn’t be part of such a conglomerate (though I suspect the current state of the Liberal Party in Ontario is probably a fair representation of its core constituency, stripped of those who might consider voting Tory). Christopher Bird has done the math and is duly annoyed.

But the more interesting question is whether it was specifically the strength of the NDP and the resultant exacerbated fracturing of the non-Tory vote that handed Stephen Harper his majority. Eric Grenier thinks so. Me, I’m not so sure. For one thing, it’s an argument that relies on assumptions that are awfully difficult to test: if the Liberals lost a large number of raw votes in a particular riding, how do we know where they went? And if they failed to attract a significant share of new voters, who’s to say those voters would have come out at all if they hadn’t been enthused about the surging NDP (or the oh-so-reliable Tories)? A strong NDP is one thing – a weak Liberal Party another.

To push the argument a little further, let’s conduct a bit of a thought experiment. Let’s say the Grits had held on to their base: everyone who voted for them in 2008 came back in 2011 to support them again. Tories and Dippers may battle out the fight over new voters between them (given that the Liberals only managed to attract those types in two GTA ridings, and only a few hundred of them there). Under those premisses, with no-one taking votes away from the party, how many of the seats they lost to the right last week might they have retained? Eight. And even in those cases, it’s not at all clear that electors abandoning the Liberals for the NDP are to blame.

Take Pickering-Scarborough East. The newly elected Tory MP won there with 19,220 votes over the Liberal incumbent’s 18,053. The Grits were pummelled in Pickering, losing over 4,800 of the people that supported them in 2008. But wherever they went, it wasn’t wholly to the left. The Conservative vote increased by 4,280 since the last election, but only 1,958 more voters went to the polls in the riding this year – even if they all voted Conservative, the Tories still got over 2,250 votes from elsewhere. And unless everyone abandoning the Greens decided to support Harper’s party, the Liberals only have themselves to blame in Pickering: the Tory candidate was elected not by default, because too many left-leaning Grits left for pinker climes, but because too many right-leaning Liberals decided they’d rather have a Conservative than a social democrat as their prime minister.

Nowhere is this particular tendency more frustrating to observe than in Etobicoke-Lakeshore, Michael Ignatieff’s riding. Sure, the NDP did reasonably well there, attracting over 5,000 new supporters. But that’s not why Ignatieff lost. He lost because a sizeable portion of the over 4,400 voters that decided to leave the Liberals behind turned to the Tories instead. Bernard Trottier won the seat by raising the Conservative share by almost 4,200 votes. But there were only 3,320 new electors in the riding this year – and not all of them will have voted blue. Let’s assume half of them did, though (less a reasonable than a very generous assumption). That still would have left the Tories 2,500 votes shy of their eventual total, and unless we again think of Green supporters as long-lost right-wingers, the only place to recruit those missing thousands was the Liberal Party. If those voters had stuck with Ignatieff, he’d have hung on to his seat.

The same picture emerges in Willowdale, in Scarborough Centre, in Etobicoke Centre, and in Don Valley East. In all those ridings, the Conservatives gained more votes than the increased turnout could have yielded, even if every single new elector had supported them. In all those ridings, Grits and Tory numbers are close enough that centre-right Liberals voting for their party would have made the difference.

The strength of the NDP didn’t help, of course. It likely drew more new voters to the left, forcing the Liberals to shore up their base. But the problem in the GTA was not that the NDP drew core supporters away from Ignatieff’s party. Such a movement may have been behind the loss in Mississauga East – Cooksville (where the number of new voters exceeded the Conservative’s gains, so that we can’t know whether any Liberal supporters turned to the right). The single riding where a massive leftward shift clearly handed the Tories a seat they should never have won is Bramalea – Gore – Malton. There, the NDP gained an astonishing 13,424 votes, likely drawing most of the almost 6,000 voters that abandoned the Liberal incumbent and taking the lion’s share of new electors, but still fell over 500 votes short of beating the Conservative candidate.

But that riding is very much an exception. Time after time, the same pattern repeats itself in the election data: Conservative gains exceed the total number of new voters, pointing to a migration of Liberal core supporters to the right. There are only two other new Tory seats that don’t follow this logic: Brampton West, where the Liberal incumbent’s base grew by a few hundred while his Conservative challenger laid claim to almost 7,000 of the over 9,000 new voters; and Ajax-Pickering, where Mark Holland’s support held steady as he watched his Tory opponent sail past him with the help of over 6,000 of the riding’s 7,600 new electors.

In sum, the Liberals didn’t lose Ontario because the NDP sapped them of their power. They lost partly because of their inability to convince new voters that they were the best choice; but more importantly, they lost because unlike in 2008, when a large portion of their base simply stayed at home, in 2011, a significant segment of those that had bothered to come out three years earlier decided to cast their lot with the Tories instead.

Three Final Thoughts

I suppose this isn’t exactly the pithiest post of all time. I’ll try to right the ship in this final section.

Thought the first: I find the suggestion that Quebeckers didn’t vote for a party or a platform when they supported the NDP but simply voted for Jack Layton – an argument made by every other talking head, in papers, on blogs, and TV and radio shows all over the country – totally facetious and appallingly condescending, as inane as the proposition that the NDP profits from being a “populist” party. That Layton is popular and populist in his appeal is beyond dispute. But to argue that Canadians had no idea what the party they were supporting stood for seems baseless to me. My point is not that everyone who voted NDP is wholeheartedly in favour of the party’s platform (or even fully aware of it). But the vast majority of people who voted for the party will be aware and in favour of its broad political orientation and ideals. A few lost souls may have inadvertently supported a social democratic party or party leader, much like a Democrat voting for the ever companionable George W. Bush under the mistaken assumption that he wasn’t a Republican. But I find it impossible to give credit to the notion that hundreds of thousands of Quebeckers in particular bothered to go to the polling station to elect candidates whose party’s policies and ideals have nothing to do with those voters’ ideals and wishes for their society. They may not be strong and lasting supporters of the NDP as a party, but they represent the large majority of centre-left Canadians.

Thought the second: Who exactly are “Canadians”? In the days after the election, the ineptly named polling firm Ensight taught us that “Canadians” wanted stability above all and were sick of the endless string of short-lived governments. I’m happy to believe that those were the views expressed by Ensight’s focus groups, but why didn’t “Canadians” as a whole vote for a majority government in that case? 40 percent of people who found the time and energy to show up did, and in our electoral system that’s enough for a majority of seats – but how and why do those 40 percent come to stand for all of us? What’s more, what happened to the 60 percent of electors who clearly did not vote for Tory stability? Where were they in Ensight’s focus groups? And if those groups were as unrepresentative as their answer to this central question suggests, how reliable or meaningful are their answers to other, more nuanced questions?

Thought the third: There’s a huge difference between a wave of popular support, as in Quebec, and a wave of newly won seats, as in Ontario. (I sort of hinted at that above. Ahem.) But that difference has direct consequences for campaign strategies – in Quebec, the NDP’s candidates and their presence in or absence from their ridings turned out to be completely immaterial. If a wave is rolling over the province, it simply doesn’t matter who’s on the ground. Turns out, that’s not how things worked in Ontario. I can only rely on anecdotal evidence here, but from riding after riding I’ve heard stories of Liberal incumbents who didn’t bother campaigning door-to-door, didn’t show up to debates, didn’t run thorough canvassing operations, didn’t even (in the case of the party leader) live in the riding. Much as Ignatieff during the English debate, the Liberal Party campaigned as if they were still the obvious choice for voters: as if they didn’t have to make their case in ridings that were already theirs. I never, ever agree with Margaret Wente, the odious Globe and Mail columnist, but she’s right on this one: the Tories won in Ontario because they had their ground game in order, took a long-term and locally specific perspective, and sold their candidates to voters on the riding level. It didn’t help that Canadians apparently weren’t won over by Ignatieff, that the national campaign didn’t catch people’s imagination, that the Harperites orchestrated a sleazefest of negative advertising, and that the NDP was surging. But the Conservatives could never have won a majority if Liberal candidates, and Liberal incumbents in particular, had persuaded their base to stick with them and had attracted at least a small share of new voters. As it turned out, Ontario Liberals simply didn’t give people a reason to support them. Quebec was won in the thrill and abandon of a surge. Ontario was lost, ploddingly, on the ground.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

2 Responses to An Election Lost and Won

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.

I think you’re basically right. I suspect that a bunch of small-c conservative Liberals ditched for the big-c Conservatives in the last day or two of the election. In particular, that theory explains how the polls all underestimated the Conservative vote by so much.

It’s interesting to hear about the Liberals’ alleged lack of a “ground game” in Ontario. We didn’t have any sense of that here in Alberta, where there wouldn’t have been much point in a ground game from the Liberals. Certainly, the Liberal candidate in my riding (Edmonton-Strathcona) didn’t come knocking on my door, and no leaflet from him dropped through my mail-slot to keep company with the leaflets from Linda Duncan and Ryan Hastman. But I did assume that it would have been a different matter in Ontario. Perhaps the lack of a “ground game” here makes the statistics from Edmonton Centre, where, the NDP and the Liberals combined won more seats than the Conservative candidate, more important than I thought. A headline like “All but one Edmonton riding goes to Conservatives” doesn’t begin to capture what unfolded. That’s a long way of saying that I appreciate the kind of analysis you’re offering here.

As for “Thought the First,” the “populist” Jack storyline as you put it or the “Good ol’ Jack” storyline as I would, I think we need to talk about the flipside, which was the mainstream media’s refusal to let Ignatieff ever become “Mike.” I’m not sure how or when Ignatieff became “Iggy,” but the tale I haven’t yet heard told — point me in the right direction, if I’ve missed something! — is one in which a smart man with soft grey eyes talking about compassion and pleading with Canadians to “Rise up!” got caught in a vice-grip between a bully and fighting-Jack — or squeezed out of a playing field with a decidedly masculinist edge to it. I saw it happen before my eyes in Edmonton where I attended both Layton’s and Ignatieff’s rallies, and watched Layton’s soundbites translate into punchy headlines while Ignatieff’s substantive claims got no coverage at all. The Gore-Bush debacle in 2000 showed us only too starkly what the North American media does to political candidates who happen to be smart men. I can’t help thinking that Ignatieff wasn’t giving the press a masculine persona with which it wanted to work, and so he got shunted to the sidelines. Sure, that’s not all of the story by any means, but it’s a part worth taking account of, especially since the tale of Jack’s visit to a certain massage parlour featured in it. Did Ignatieff *fail* as the Globe’s endorsement of Harper famously claimed? Or did we fail *him* even as we endorsed the narrative that Jack was someone we could vote for because he is “one of the guys”?