Steven Moffat Does It Again

Needless to say, this is a spoilerfest.

I had my problems with all of Season 3 of Sherlock, to be honest. “The Empty Hearse” was overstuffed with endless montages of swooping shots of Central London and hectic jump cuts around the Tube, all of which seemed designed to illustrate mental activity but really only worked as visual filler. Aren’t the floating text bits a little stale and cheesy by now? And what about that music? Where did all those soaring, blockbuster-style strings come from, and what are they supposed to tell me? Most disappointingly, though, I thought the resolution of the flimsy plot was unspeakably callous — if Holmes is this nasty, why should Watson still be his friend, and why should we remain interested in him at all? (A friend of mine has aptly described both Moffat’s Sherlock universe and the world of his Doctor Who as largely devoid of consequences: neither male hero is ever made to regret anything lastingly and consistently. There’s always eventually an out. No matter how much Sherlock acts like a total and utter shit, Watson will be there for him.)

But whatever — that’s me. (There were good things, too. I liked that they left open the question of how Sherlock pulled off the stunt that ended Season Two, although that could also be seen as a fairly major cop out. Mycroft’s expanded role largely works. The Les Mis jokes were funny.)

“The Sign of Three” struck me as one huge exercise in fan-service, with an even less interesting and even more implausible case than the first episode. At this point it seems obvious that Sherlock, for better or worse, is not really a detective show anymore. Partly, that’s because the cases themselves simply suck. Partly, it’s because Gatiss and Moffat have written themselves into a corner with this season’s version of their detective. Sherlock as a character is now so much of a so-called “high-functioning sociopath” that he cannot read people’s responses and can’t recall the names of police officers with whom he has worked multiple times; but he’s ALSO rivalled only by his brother in his ability to read people. It’s one thing to be an expert interpreter of clues who is emotionally aloof and profoundly indifferent to the feelings of others (in many ways, that’s now Mycroft’s character). It’s quite another thing to be incapable of understanding a whole range of emotions. Doyle’s Holmes was the former in his worse moments, but never the latter. Gatiss and Moffat’s Sherlock, as they keep reminding us, is clearly the latter — his behaviour is pathological, not a matter of choice. I don’t see how someone with as limited a vision of human interactions as this season’s Sherlock could ever read correctly the signs and traces of the myriad of human interactions he observes throughout the three seasons. This is now a broken character.

But whatever. Consistency be damned.

And then came “His Last Vow.” A wonderfully creepy villain — viscerally unpleasant, and quite funny too (the T-shirt joke? Gold. The flicking of John’s face? Marvellously vexing). And the revelation of Mary Watson as international assassin. Interesting.

Unfortunately, what came with “His Last Vow” was the reappearance of Moffat’s tried-and-true knack for writing plots more sexist than the Victorian originals he draws on — a skill on fine display in “Scandal in Belgravia,” and no less evident in this latest episode. Charles Augustus Magnussen is based on Charles Augustus Milverton, “the worst man in London.” Many details of Doyle’s story find their way into Moffat’s plot: Sherlock’s engagement to Magnussen’s PA is straight from Doyle (though Holmes is marginally less callous about it), Sherlock’s repeated miscalculations in his struggle with Magnussen are mirror-images of similar errors of judgment Holmes makes when sparring with Milverton, and both plots end with the blackmailer getting shot. There is one crucial difference, though.

Here’s what happens in “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton.” Holmes and Watson have broken into Milverton’s house to steal incriminating documents from his safe. Holmes is certain the villain is asleep. Holmes is wrong. He is in fact meeting with a veiled woman who seems to be about to sell him new material. As Holmes and Watson watch from behind a curtain, this is what unfolds instead:

“–Great heavens, is it you?”

The woman, without a word, had raised her veil and dropped the mantle from her chin. It was a dark, handsome, clear-cut face which confronted Milverton– a face with a curved nose, strong, dark eyebrows shading hard, glittering eyes, and a straight, thin-lipped mouth set in a dangerous smile.

“It is I,” she said, “the woman whose life you have ruined.”

Milverton laughed, but fear vibrated in his voice. “You were so very obstinate,” said he. “Why did you drive me to such extremities? I assure you I wouldn’t hurt a fly of my own accord, but every man has his business, and what was I to do? I put the price well within your means. You would not pay.”

“So you sent the letters to my husband, and he–the noblest gentleman that ever lived, a man whose boots I was never worthy to lace–he broke his gallant heart and died. You remember that last night, when I came through that door, I begged and prayed you for mercy, and you laughed in my face as you are trying to laugh now, only your coward heart cannot keep your lips from twitching. Yes, you never thought to see me here again, but it was that night which taught me how I could meet you face to face, and alone. Well, Charles Milverton, what have you to say?”

“Don’t imagine that you can bully me,” said he, rising to his feet. “I have only to raise my voice, and I could call my servants and have you arrested. But I will make allowance for your natural anger. Leave the room at once as you came, and I will say no more.”

The woman stood with her hand buried in her bosom, and the same deadly smile on her thin lips.

“You will ruin no more lives as you have ruined mine. You will wring no more hearts as you wrung mine. I will free the world of a poisonous thing. Take that, you hound–and that!–and that!–and that!–and that!”

She had drawn a little gleaming revolver, and emptied barrel after barrel into Milverton’s body, the muzzle within two feet of his shirt front. He shrank away and then fell forward upon the table, coughing furiously and clawing among the papers. Then he staggered to his feet, received another shot, and rolled upon the floor. “You’ve done me,” he cried, and lay still. The woman looked at him intently, and ground her heel into his upturned face. She looked again, but there was no sound or movement. I heard a sharp rustle, the night air blew into the heated room, and the avenger was gone.

No interference upon our part could have saved the man from his fate, but, as the woman poured bullet after bullet into Milverton’s shrinking body I was about to spring out, when I felt Holmes’s cold, strong grasp upon my wrist. I understood the whole argument of that firm, restraining grip–that it was no affair of ours, that justice had overtaken a villain, that we had our own duties and our own objects, which were not to be lost sight of.

To recap: as Holmes and Watson watch, one of Milverton’s victims tricks him into letting her into his study in the middle of the night, where she let’s him have it, first verbally, then by gunfire, then with her heel in his face. And while good old Watson tries to be decent, Holmes makes sure justice, delivered by the lady, runs its course for the worst man in London.

Moffat’s take on that version of events? Good of you to ask. This:

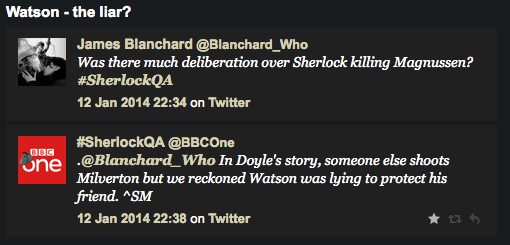

“We reckoned Watson was lying to protect his friend.” Because it’s obviously, self-evidently, naturally absurd, right, to believe that a woman could take action like that, on her own, without any help from the great man. Right? (Also: parading your friend and yourself as accessories to murder is surely a pretty feeble protective gesture?)

In “His Last Vow,” naturally, the story pans out rather differently. There is a woman with a gun to Magnussen’s head, to be sure — good old assassin queen Mary (or, as the script insists on calling her, “Mrs Watson”). But she doesn’t get to shoot her tormentor. Instead, she turns to Sherlock for help (why, exactly?) and ends up drugged and fast asleep while Sherlock, like Holmes, proceeds to be wrong about Magnussen. Then, however, unlike Holmes, Sherlock gets the upper hand yet again, when Magnussen is in turn wrong about him (the stupid blackmailer failed to understood that Sherlock is a “high-functioning sociopath”) — which costs him his life. At Sherlock’s hands. Naturally.

To recap: in Doyle, Holmes is wrong, repeatedly, about Milverton. He is lucky to get a chance to destroy the papers that incriminate his clients, but he has nothing to do with stopping the blackmailer for good. He doesn’t win.

In Moffat’s version, Sherlock is wrong, repeatedly, about Magnussen. And then Magnussen is wrong about Sherlock, and Sherlock shoots him. While the trained assassin is asleep on the sofa, presumably because she is, you know, a she. Can’t have her take Magnussen out. What an anticlimactic ending that would be. Instead, Sherlock wins, gun in hand.

OF COURSE you might say, well, it was necessary for Sherlock to kill Magnussen like that, because otherwise we wouldn’t have got Mycroft’s ever-so-devastated “Oh, Sherlock,” and the story could have just gone on, without Sherlock being banished to the Eastern European wilds. And that wouldn’t do: got to wrap things up with Sherl out of the picture after all. Oh wait.

There’s more to say. There’s the weird way in which Molly, veteran doormat of eight episodes, gets to stand on her own two sensibly-shod feet — by slapping Sherlock, over and over. Because that’s what strong Moffat women do. There’s the increasingly unpleasant way Sherlock treats Mrs Hudson. (Just not funny anymore. At. All.) There’s the nasty red herring of building up a female character capable of silencing Sherlock with a cutting witticism for two episodes; turning her into the archetype of Moffatian female strength in “His Last Vow,” by reinventing her as a vicious killer; and then taking even that weird version of power away from her — first in a way that leaves a plot hole Doctor Who could be proud of, and then by drugging her and giving her no role whatsoever to play in the resolution of her own blackmail plot. There’s the sudden extreme level of sentimentality in how Mycroft’s feelings for his brother are portrayed. And there’s Sherlock’s killing of Magnussen, coming on the heels of a long sequence of humiliations, a turn so nasty (“Merry Christmas”? Seriously?) and, in Benedict Cumberbatch’s portrayal, so out-of-control angry that it would have to read as Sherlock’s lowest moment in the season — if it weren’t for the fact that shortly thereafter he gets to kid around with Watson about baby names and then gets reclaimed as Albion’s indispensable saviour in the closing shots of the episode. In other words, if killing and hitting people is as strong as women get in Moffat, living out angry revenge fantasies is ultimately a perfectly acceptable male response to belittlement. Either way, aggression and violence are the hallmarks of the winner in Moffat’s universe; and the winner, at the end of the story, is a man.

There’s more to say indeed. But as far as I’m concerned, none of this actually trumps Moffat’s single most baffling achievement as a writer, now successfully accomplished in successive seasons: he is better than anyone else I know at taking a Victorian story, translating it into the 21st century, and making it MORE sexist than the original in the process. That’s a pretty impressively abject feat. Steven Moffat really is the king of unreconstructed men.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

36 Responses to Steven Moffat Does It Again

Leave a ReplyCancel reply

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.

And season 4 is far worse, at least so far. It’s pretty clear that everybody involved in the production is just sleepwalking towards another paycheck.

Yup. Doyle’s Irene Adler beats Holmes in a game of wits, and Holmes admires her for it. The woman in Charles Augustus Milverton rids the world of a menace and Holmes respects her choice and lets her get away with it. And while yes, this means that in those two stories Holmes doesn’t get to be the one who solves the crime, it actually says some very good things about Holmes’ character that get sacrificed in the choice to take those wins away from the women and give them to Sherlock instead. (For example, that he respects the agency and intelligence of women, that he doesn’t try to hog all the glory himself and that he understands enough about justice and mercy not to interfere and get this wronged woman hanged for a crime that’s done the world a service.)

Moffat took a female character who beats Sherlock at his own game and instead had Sherlock beat her. He took a story in which a female character killed the blackmailer and instead drugged his female character so that Sherlock could kill the blackmailer. In both stories, Moffat takes the victory away from the woman and gives it to Sherlock, thereby being less progressive than the Victorian original. It seems an open and shut case to me.

Maybe. But Conan Doyle lived in a world where female (detective) agency was a novelty or at least controversial. We on the other hand live in a world where female agency and female detectives are two a penny, the latter growing in numbers every day, not least because the majority of detective fiction is read and written by women. Switch on the TV and all you get are feisty female detectives, wearing funky sweaters, and getting the better of doltish men in a supposedly ‘male world of work’ that arguably vanished many years ago. The point in Sherlock is that it is an update, and that progress in this sense should reflect the changed reality. And by that I mean that Moffat’s Sherlock should reflect the perspective of a modern world where increasingly it is male detectives that are TV rarities rather than female. Of course you can challenge the stats – its an impression rather than a detective head count – but my point is that social justice warriordom in the particular form you seem to be pushing it, is itself out of date, and simply panders to the powers that be in today’s world.

“modern world where increasingly it is male detectives that are TV rarities rather than female”

You make no sense at all with this claim, male detectives are not rarities and it doesn’t seem to be happening any time soon. Also what does this have to do with the ladies in the original Doyle written stories with both female characters (not even being detectives) triumphing over the male characters? The point is, both those ladies were still robbed of their moments of glory in this “modern” adaption, when a male writer from the 1800s at least showed his female characters of being much more capable than that.

as soon as a show fails the bechdel test I refuse to think any further about its no doubt rampant misogynist bullshit- but I am grateful you’ve done it for this one. thx H.

“its no doubt rampant misogynist bullshit”

“No doubt.” So you haven’t even seen it? What a high standard of proof you appear to require.

[…] This way you won’t blow your wad episodes before the actual event. Somehow you manage to understand this on Sherlock, (even though it is a backward and misogynistic nightmare of a show.) […]

[…] As always, this is part of a conversation about Doctor Who. For Sherlock criticism: go here. […]

[…] more intelligent, people can better make the argument for the errors in those adaptations. Follow this link for […]

I apologize in advance for any mistakes, since English is not my mother tongue. But the “unreconstructed men” figure, as pointed out by Holger, in Moffat’s stories follow binary oppositions, black and white. Both The Doctor (Eleven fits the most) and Sherlock are given “neutrality” because of their flaws: they are incapable of creating true bonds (certainly they don’t have a problem using others) and they’re “beyond” anything related to the inner world of humans: privacy, relationships, feelings, fun. Everything else will be an obstacle for them when it comes to solve a problem. The detective and the savior are motivated by the puzzle itself, something that Moffat and Gatiss locate in the nature of their characters. Science, neutrality, reason, power: the realm of the modern man. The rest are biased, second-class beings.

Moffat and Gatiss’s “powerful” women, like Irene Adler and River Song, are constructed by chaos, lies, mystery and the inability of the heroes to understand them. The definition of women as something obscure and complex. The opposition comes full circle when you consider the social sphere: for River it was marriage, for Irene to have a date. They “force” their men back to the Real World, like something both Sherlock and The Doctor need to tame before getting back to their puzzle.

The more I think of it, the more I get angry. Let’s get back to Forbrydelsen’s Sarah Lund.

“The detective and the savior are motivated by the puzzle itself, something that Moffat and Gatiss locate in the nature of their characters. Science, neutrality, reason, power: the realm of the modern man. The rest are biased, second-class beings.”

But if they were not motivated by the puzzle itself, what would they be motivated by? Compassion? Love? A fascination by human psychology. All of those thing are perfectly good motivations if you can squeeze mystery & drama out of them. But that’s not going to work for Dr Who, or Sherlock Holme’s, so if you have a problem in this regard, then you would appear to have a problem with the characters and therefore the programmes themselves. If you don’t like Dr Who, or Sherlock Holmes, don’t get angry and frustrated, just don’t watch it. Vote with your feet.

You seem to like Sarah Lund. Great, so do I. But why should you oppose her to Sherlock & Dr Who? Why are they in competition? I love Sherlock and I love the Killing. And the woman detective in Fargo, and the flawed slightly autistic female captain in Engrenages. Why are they good and Sherlock / Dr Who bad? Perhaps it’s you who are setting up the binaries.

My understanding of the feminist / postmodern criticism of binaries is, crudely, as a critique of gender essentialism, and particularly of that process whereby we identify one class of people in terms of another (subjugated) class, particularly where the latter is somehow ‘Othered’ in the process of doing the essentialising. I take the point about ‘chaos, lies, mystery’….or whatever it is that women are and men should not be….

But look at how you criticised Sherlock & Dr Who, – “they are incapable of creating true bonds (certainly they don’t have a problem using others) and they’re “beyond” anything related to the inner world of humans: privacy, relationships, feelings, fun”.

Did you not just ‘other’ those characters. You described them in terms that suggest they are not only flawed as fictional characters but somehow not fully human, not quite real. Not quite deserving of sympathy, compassion, love etc? What’s more you did so with the full confidence of one speaking from within a dominant set of values: the values of say, privacy, relationships (bonding), feelings (emotions), values which are everywhere held up as what being human is all about. You then suggest someone like Sarah Lund as the sort of character we should hold up as an appropriate model. But you don’t describe Sarah Lund at all. The only thing we know about her from reading your post is that she is defined against the masculine characters you find so deficient as human beings. Your personal Other.

So by setting up Sarah Lund as an alternative to Sherlock and Dr Who, aren’t you just putting forward essentially feminine values as a binary to the now largely subjugated masculine values.

Its not that your wrong, its just that you’re no different or better than Mr Moffat & co. The only difference is nobody’s trying to unravel the wool from Sarah Lund’s jumper

I found this because your “baffling achievement” quote is making rounds on tumblr with a lot of agreement

http://crimsonclad.tumblr.com/post/73474334735/but-as-far-as-im-concerned-none-of-this-actually

Thank you for writing this.

Okay, so I don’t normally make a point of getting into heated blog discussions/arguments on the internet, but I’ve heard this kind of argument a few times since Sherlock S3 aired and I really do have to disagree with a lot of what you’re saying.

Firstly, I’d like to preface things by stating that I am not generally a fan of Moffat’s female characters – the man’s writing has many flaws which should all be acknowledged. I’d also like to state that there are certainly things in S3 that I take issue with. What I’m trying to get across is that I’m not merely defending the show out of some sort of misguided loyalty towards it.

However I really do feel (without trying to be rude) like you’ve missed the point of this series on so many levels. Gatiss and Moffat have not “written themselves into a corner with this season’s version of their detective” as you seem to think because Sherlock is not a ‘high-functioning sociopath’ and never has been. The Sherlock of this adaptation has always felt emotion, he just expresses it in an atypical way. And how you construe Sherlock forgetting Lestrade’s name as evidence of him being a ‘sociopath’ is beyond me – that could be an indicator for any number of things, but I think in all likelihood is a reference to the fact that in ACD canon we never actually find out Lestrade’s first name. If anything, this series shows us just how deeply Sherlock does feel emotion; they literally hammered home the idea that Sherlock will do anything for John. Magnussen backed Sherlock into a corner and Sherlock did the only thing he could think of to protect the person he loves most; he killed Magnussen even though doing it frightened and upset him – the shot of young Sherlock crying is the evidence for that.

Sherlock’s actions do not make Mary a less strong character because they have nothing to do with Mary. The trained assassin is not asleep on the sofa “because she is…a she” but because the writers wanted to show us Sherlock’s character development, through his dedication to John. And as another commenter said – Mary was pretty heavily pregnant at that point in the timeline!!! Aside from that I resent your suggestion that Mary’s being referred to as ‘Mrs. Watson’ is implicitly sexist. Yes, the idea that a woman should need to change her name when she gets married is built on sexist traditions, but the show isn’t saying that she has to. The point is that Mary wants to, because this is the life she has chosen and created for herself, and she is perfectly happy with that life. And if you disagree with me on that, and think that Moffat was referring to her as ‘Mrs. Watson’ because he believes women should change their names, then how about considering the fact that Moffat’s wife didn’t change her name when they got married?

Sherlock has never been the best show in terms of representation of gender (among a number of other things) but I really feel that if you wanted to make that point you’d have been better off using different evidence.

These arguments always founder on the rock of character. I’m not talking about character. Sherlock isn’t real, neither is Mary. Whatever either does or is they do or are by virtue of what the writers decide they do or are. What I’m interested in, therefore, is plot. Mary “isn’t” pregnant. Mary becomes irrelevant to the fight against Magnussen by virtue of the fact that Moffat and Gatiss write her out of the plot — as a pregnant lady. You and I can infer all sorts of things about what fictional characters may feel or think, and widely divergent opinions can be sustained by the same evidence. I’m not interested in this kind of argument, and I’m not making that sort of point. My point is really quite simple: women play particular and active roles in two of the source stories of Moffat and Gatiss’s Sherlock. When they take those source stories and adapt them into their own, they consistently remove agency from women and transfer it to Sherlock.

I don’t know why they do this. I think the fact that they do it is pathetic and weakens the show — not because it’s necessarily sexist, but because it reduces the show to a story that’s all about Sherlock (and little, teeny bit about Watson). Doyle’s stories aren’t actually like that at all. So I don’t disagree that the show has become ever more about Sherlock as a character — but I think that is probably its biggest flaw now (the same is true of Doctor Who).

Two small points: you’re inferring much more about the “Mrs Watson” thing than I said. You’re also inferring much more about Mary than the show makes explicit. Again, I don’t care about a fictional characters imputed motives or feelings. I care about representation. And the way the show keeps pushing the “Mrs Watson” tag strikes me as extraordinarily fusty — I don’t know anyone in my extended circle of friends (which isn’t especially homogenous in political persuasions) who would constantly refer to his spouse as “Mrs X.” Secondly, that shot of the crying child Sherlock? I took that as a reflection of Mycroft’s mental image of his brother, not of Sherlock’s state of mind (it follows on a close-up of Mycroft’s face). In any case, what that image is supposed to illustrate is entirely open to interpretation — it may well signal that Sherlock is emotionally on the level of little kid!

“I don’t disagree that the show has become ever more about Sherlock as a character — it’s probably its biggest flaw now”

As far as I’m aware most primers on how to write a best-selling script seem to say that plot should follow character rather than the other way round, but you seem to think that both should be in the service of a particular politics of representation. Surely the first rule of narrative shouldn’t be a political one?

We already have one show, Elementary, that seems to have followed the route of updating Conan Doyle to meet the imperatives of representation. It violates the canon in similar ways, but in a direction that seems intentionally ‘progressive’ (as evidenced by direct references to ‘partnership’ and ‘equality’) and ironically the main casualty appears to be the characterisation of Holmes, who seems slightly diminished, not quite so clever somehow.

It is true that Fanboys tend to endow characters that don’t exist with a dimensionality that suggests they are real, just as old ladies like to ventriloquize for their pets to express their ‘thoughts’. But when this (the former) happens doesn’t it often reflect powerful writing, usually because characters the viewer cares about have been put through trials and tribulations (that is through character based plotting) just as happened in the Last Bow.

As yet we have no real connexion with Mary so it would not have made sense for her to be tested in this way, that is represented as the agent of Magnussen’s demise.. For Mary to have pulled the trigger in the Last Bow does not create any kind of crisis of character, nor would it lend anything to the plot in terms of dramatic conflict. If on the other hand we ask ‘would Sherlock commit murder if it was the only way to save his best friends marriage?’ that is a question that will provoke controversy, debate and above all an emotional reaction, as it has indeed done.

But none of the above is important because your point is about representation not character. Is that not the same as saying you do not care about the show but you do care about its politics? If so, perhaps you should declare your interest in its demise.

I find Elementary unwatchable, so can’t comment on that.

If the episode was designed to lead up to the question you raise, it was a horribly plotted episode — because that’s surely not the question it raises at all. I agree that it would be a controversial question to ask, if a mildly crazy one. However, what’s actually at stake is Mary’s life (as Magnussen makes clear) — which in fact lowers the stakes, as Sherlock is arguably taking one life in order to protect another.

As for the politics of representation, you’ve rather misunderstood my point. I don’t think any particular narrative has to follow particular political principles. As I said in an earlier comment, there is no mandate here. But once you’ve told your story in a particular way, it becomes subject to criticism. I’m not saying Moffat has to write differently — I think it’s pretty clear at this point that he probably can’t, and certainly won’t. But I am saying that the way he writes is problematic for a number of reasons. One of those is “political,” if you will. (I should point out that when I say “representation,” I don’t mean “equality” — I mean mimesis.)

I will say this, though: I think it’s indicative of something that Holmes as character VERY rarely gets to dominate Doyle’s stories. He’s a key element in them, but so is Watson, and most importantly, so are the cases they investigate. The stories aren’t about Holmes, they are about his work. I really don’t think this is true of Sherlock anymore — it used to be, but this season, the balance shifted. Now, this is a show about a character. And I do think that’s a major problem (not for political reasons, but for narrative ones).

“What’s actually at stake is Mary’s life (as Magnussen makes clear) — which in fact lowers the stakes, as Sherlock is arguably taking one life in order to protect another.”

I am not sure Sherlock would make a distinction between saving Mary’s life and saving his best friend’s marriage. I suspect ‘this’ Sherlock sees Mary as instrumental to his best friends happiness rather than as part of any greater kingdom of ends so to speak. Otherwise how could he kill Magnussen? He saves Mary because of her value to John Watson. It is a troubling logic but one that reveals character in a way that any other plot configuration would not.

“I find Elementary unwatchable, so can’t comment on that.”

That’s because with Elementary there’s no real grist for the critical mill. With Elementary the kind of concerns you raise have already been addressed in Elementary at the “planning committee stage” so to speak. Elementary is what Sherlock becomes if the criticism you make takes root.

“But once you’ve told your story in a particular way, it becomes subject to criticism. I’m not saying Moffat has to write differently — I think it’s pretty clear at this point that he probably can’t, and certainly won’t.”

Moffat may well be a bit unreconstructed but I think that’s probably unfair. I suspect Mary is in part the child of last year’s criticism and if that is the case you may well share a degree of paternity (after all you criticised the Scandal in Belgravia episode). Mary is quite likely Moffat and Gatiss’ not entirely convincing effort to ‘get with the programme’ in terms of ‘positive’ representations of women: “Moffatt: “they’re banging on about sexism again because I had Irene Adler get her kit off. How do I get them off my back? (Gatiss: I don’t know, let’s ask Robin Thicke?”)

That’s certainly how Mary was born. So when you say a work told in a particular way becomes subject to criticism it probably does mean that Moffat has to write differently; will have to adapt his writing in anticipation of the kind of criticism that can make life very hard for any who don’t instinctively share the consensus view on how gender should be represented in media to be ‘inclusive’, progressive, pass the Bechdel test etc

So if Season 4 ends up as neutered as Elementary it could well be your fault (J’accuse). But I really hope that Moffatt and Gatiss can show some defiance in this regard. Not because sexism is a good thing. These days most people are turned off when ‘representations’ become offensive or cliched – but there is a type of criticism ( particularly from the …err…let us say critical schools) which may achieve its effect through attrition. At its worst – and with relevance perhaps to your concern with mimesis – this type of criticism can become indistinguishable from that found on sites like feminist frequency where quite incisive analysis simply becomes a weapon to hammer creativity into submission. So please don’t hammer Cummerbatch into Johnny Lee Miller.

It is simply a waste of precious creative resources for writers to be constantly on the lookout for the police so to speak, Sherlock shorn by the Delilah of anti-sexism becomes Elementary. So please don’t snip off our Sherlock’s golden locks.

Let character dominate & plot will follow

I pretty much agree with everything that Alex said (including the part where I agree that Moffat is sexist and that Sherlock does have some major issues). However I would also like to add that you complain about Moffat defining women by the leading man (or men), but you are defining the women yourself by the mens actions.

In fact you talk about how Sherlock’s actions in HLV change and define Mary as a character. That by Sherlock being the one to stop Magnusson that this makes Mary a weaker character. Consequently you are practicing what you are complaining about. Personally I don’t see how Sherlock shooting Magnusson (or in fact drugging everyone) has any effect on the fact Mary is a kick-ass strong independant woman.

In addition the concept that pretty much every female character introduced in Sherlock is a puzzle for Sherlock to solve can be said of pretty much every male character in the show. He is a detective solving mysteries at the end of the day. What exactly do you expect?

Lastly you talk about not wanting to pay attention to the details or the ‘implied’, but at the end of the day that is pretty much what Sherlock is about. Moffat and Gatiss have explicitly stated on numerous occasions that they like to leave a fair amount of the plot and characters backstory for the audience to speculate/figure out for themselves as they like to treat their audience as intelligent beings who don’t need everything spelling out for them. So essentially if you are going to take a show purposely made to allow people to make their own deductions on face value then you aren’t going to get very far… In fact I’m slightly confused as to why you would watch it considering there are 1000’s of other shows out there you could watch in which you can take everything on face value.

Can someone else take this, please? I’m tired.

“I’m slightly confused as to why you would watch it considering there are 1000′s of other shows out there you could watch in which you can take everything on face value.”

There are some villains we love to hate. Usually that refers to a character in the show but in Holger’s case its the writer. Its pretty obvious he loves Sherlock

I think the disconnect here, is that you are treating Mary Watson as a person, while Holger Syme is treating her as a part of the story.

Sherlock’s actions don’t change the nature of Mary’s character. But being conveniently incapacitated at vital moments hamstring her importance as a character. If she can’t make any real difference at crucial junctures, then she may be a kick-ass strong independent woman in theory, but, practically speaking, she’s just window dressing.

In the original story, the woman stole a good measure of agency from Holmes and Watson by taking the climatic confrontation with the blackmailer from them. As a person, she did nothing to them. As a character, she demoted them from heroes of their own story to a footnote in hers.

It’s the opposite of the tactic you see in a lot of modern-day films, where they have “strong women” who just happen to be absent (or mysteriously useless) at crucial junctures. A tactic that got used in HLV.

But, obviously, Mary being incapacitated is hardly a slight to her as a person.

Bingo.

The problem I see here is that Moffat wrote a lot of strong women characters (Nancy from “Empty Child”, Madame de Pompadour, Sally Sparrow, River Song, etc. etc. and then some people didn’t like his characterization of the “derived” Irene Adler, so they smacked on a misogynist label. Ever since then, they’ve been turning themselves into corkscrews to try to justify that label and can’t. This is just another example. Ooh, Mary is left out of the denouement. Ooh, Mary is left on the sofa. Bad, nasty Moffat. If Mary doesn’t leap about, changing her clothes in a phone booth and resolving the situation, you’re all disappointed. You lose sight of the fact that the show is not about Mary Watson.

Look, she’s a strong woman character — yes, just like Irene Adler — but the show is about Sherlock Holmes and John Watson. Just let the sexism accusation drop. It was nonsensical to begin with and simply becomes more so as time passes. Okay, you don’t like some of the characterizations in Sherlock; there’s other TV out there to watch. But for pity’s sweet sake, just let the absurd sexism label go. It never made any sense and — you know what? — it still doesn’t.

I like this. sablin27, Good show.

Mary isn’t ‘the woman’. She’s just appeared on the scene as Dr Watson’s girlfriend / wife. Why on earth would Moffat and Gatiss inject her for no reason with so much agency that Sherlock & Watson would be left twiddling their thumbs. In all likelihood she has as much agency as she has (a very considerable amount) because Moffat and Gatiss have gone down the line of appeasing critics rather than focusing on the story. That’s to say Mary is not obviously an organic outgrown of ‘the story’ she is ‘part of’. She’s been unnaturally hammered in to please critics with agendas. Instead of objecting to the violation of the narrative this represents you would have the writers engage in further hammering in, more ‘narrative of appeasement’.

This is not to say that women should not have agency within narrative, but that when it happens…and it happens all the time….it should be organic rather appeasement, or quota, or barely disguised feminist bullying.

Representation may be important (depending on the wider political / aesthetic aim) but here it jeopardises integrity.

As for the woman herself her demoting Sherlock & Holmes from their own story had a point a century ago. It shook Holmes and presumably the readership’s complacent assumptions about the world around them. The world is now in no small part politically reversed. Adler’s independent woman is now orthodoxy rather than ‘violation of expectation’ and Sherlock and his viewers have nothing to learn from her – there would be no shock to discovering that a ‘mere’ woman had outwitted the great (male) detective. The parabolic significance of the ‘the woman’ cannot be reproduced in the modern world.. Indeed it would seem like just one more instalment of progressive paint by numbers iconoclasm, an iconoclasm that insists upon ‘art’ being subjugated to (progressive) politics.

I do fear there is a (Canadian feminist) incentive system for making these kind of attacks. Just as Moffat and Gatiss must appease, so must those who hold position seek to please powerful constituencies. So perhaps both Moffat and Gatiss need to be freed of a pressure to appease that violates their ‘art’ and critics like Holger (and Extremis) need to be freed from their eagerness to please their audience.

Forgive my impertinence here, but I do think there is a sense in which male critics need to consider whether the reward systems in place for making the right kinds of noise may influence what they say beyond any prior political orientation

Look at all the Fanboys defending Moffat. – Makes sense.

It’s pretty nauseating, but I expect Moffat to have his group of defenders who would overlook his sexist crap.

Stephen Moffat – public enemy number one for social justice warriors. I’m very tired of the constant campaign within fandom to make liberal feminist viewpoints mandatory and demonise those who don’t hold them.

Mandatory? The man can write whatever he wants. But if what he wants to write manages to be more reactionary than a story that’s over 100 years old, he’s going to have to live with the criticism as well. It’s not like anyone’s petitioning the BBC….

People like equal rights and proper representation? Shit, that must be tiring for you.

Give me a break. Did you live through “womens lib”? I did and the stories I could tell would horrify you. Back off and look at Moffat’s body of work objectively. If you can.

Tiring for anyone pointing fingers at “social justice warriors” instead of thinking critically. Anyone who will discuss sexism in writing must be paranoid and sensitive, that’s what they must think.

Brilliant but loopy analysis Holger…you’re definitely the sherlock of detecting sexism. But to end your piece on “Stephen Moffat really is the king of unreconstructed men” is to imply that Moffat and the characters he writes (Dr Who & obviously Sherlock) should be reconstructed too. Ignoring Dr Who for the moment if Moffat reconstructs Sherlock what would he be reconstructed as exactly? The whole high-functioning sociopath is pretty much a literary amplification of the Baron Cohen autistic male brain as the essence of masculinity theory. But a reconstructed autistic male brain is arguably no longer autistic, or aspergers or whatever. Such a reconstructed male brain would be capable of empathy and mind-reading (beyond pyrotechnic feats of meta-cognition put on for show). Perhaps that is precisely why Sherlock is your target : that is, because he represents a kind of essentialist masculinity – emotionally dysfunctional, heroically sociopathic – that’s stands at odds with the wider project to make men more womanly and women more like men, which is the reconstruction we see happening all about us every day, in film, theatre & TV, typically celebrated as the highest form of artistic creation by all but the ordinary people who actually do most of the watching of films or the reading of books. To reconstruct Sherlock is not to give Mary a bigger more decisive part (she has already been touted as a character who,in the next season, might join the partnership of Holmes & Watson to make it a subtly feminised triumvirate); rather it is to mute precisely those arguably extreme characteristics of masculinity – man as a pure cold reasoning machine bereft of emotions or empathy – that Moffat’s Sherlock amplifies even further (even while enlarging on character relationships in a way that Conan Doyle never would). So from the perspective of reconstructing errant masculinity Sherlock (and Moffat) was always going to fail, because the very project, the resurrection of a character who some would like to see consigned to the canons of a discredited literature, was always about a character who was essentially male, but who represented a masculinity which (notwithstanding Sunday’s bullet to the head climax) is about intelligence and the value of reason rather than viciousness. Masculinity is everywhere associated in the modern mind with violence and aggression. Sherlock represents a different, flawed, but occasionally better, even superior kind of masculinity. But of course you want to reconstruct that, and in so doing neuter it. Perhaps Moffat in Season 4 Sherlock should try to solve his crimes with intuition.

One last word thing though, you do Moffat’s Mary a real injustice. She’s a dynamic character. In every episode so far, despite being the new girl on the block, she has been instrumental in saving her future husband’s life (she recognised the skip code); saving her husband’s commanding officer’s life (she remembered his room number and effectively persuaded the officer from taking his life) and in the last episode not only (by Sherlock’s admission) saving Sherlock’s life, but holding that life in her hands and determining its fate. So in all three episodes Mary, who your post suggests has been viciously neutered and disempowered has made damsels in distress of the male characters including the hero, just as she has been built up as a force to be reckoned with – an equal – as some have argued – to Sherlock himself. But to those who have it in for Moffat, and Sherlock himself it seems – the creation of a dynamic female seemingly designed to ensure that Sherlock doesn’t devolve into a Holmes / Watson mutual masturbation club, just isn’t enough. She’s supposed to shove them out of the way, not only incapacitate Sherlock but eliminate the super-villain himself. But hang on how would that work? All we find out about Mary is that she’s a CIA assassin who’s killed a lot of people. Sherlock faces Magnussen as someone who has the perspective to assess the evil he represents. Mary could only kill Magnussen as a continuation of her function as assassin – which is the part of her life which she is seeking to sacrifice by marrying the genuinely good, and forgiving Dr Watson. Dr Watson makes the ultimate gesture of trust by not prying into the details of her past, and in so doing he frees her from what she has done so she can make a new life with him. Up until that point her humanity had hung in the balance – by by being trusted by her new husband, she receives grace for crimes past, a remission of sins.

From that point Sherlock’s mission becomes the mission to save not only her life but to ensure the future happiness of his best friends, a couple he proclaimed he would do anything for in the previous episode. Now on what planet would it have made sense for Mary the ex-CIA assassin, having convinced her husband that her slaughtering days are over, to have concluded Sunday’s episode by cold-bloodedly shooting her adversary in the head?

When Sherlock shoots Magnussen in the head he’s not patronising her, he’s sacrificing his life for his friends.

Thank you, Billy Bob! It’s so nice to see a reasonable person attack these ridiculous theories and diatribes. You have saved me so much work. I owe you one!

You’re welcome, thanks. I didn’t think the criticism was fair. Holger is a critic of some repute but this seemed to be ideologically motivated and frankly petty.

While the trained assassin is asleep on the sofa, presumably because she is, you know, a she.

Give her a break; she was about eight months pregnant! Even in her professional-assassinating days she would have been booking a bit of mat-leave rather than seeking out helicopter journeys.