Old Spaces, New Art: The Theatrical Avant-Garde and the Proscenium Stage

I have been thinking quite a bit about the problem of theatrical space lately. Open any survey of theatre history, and you are likely to find a fairly standardized account of how the spaces — the buildings, mostly — used for theatrical performances in the West have developed. Without too too much distortion, one could describe that account as the story of the rise and fall of the proscenium stage, as theatrical space moves from its democratic origins through monarchic single-point perspective back to a supposedly more democratic (in-the-round, open-concept, black box, or thrust-stage) architectural form.

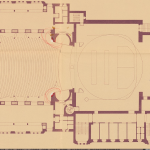

A curious feature of this standard account is that it tends to treat playhouses as if they weren’t built to last, as if the emergence of a new kind of theatre meant the disappearance of other theatrical venues. This may be a problem of teleology, or perhaps just the inevitable side-effect of avantgardist thinking — a focus on the cutting edge that loses sight of the (usually much larger) rest of the knife. And because I am spending most of my time thinking about the 1920s at the moment, I have noticed another curious displacement: that of the actual in favour of the theoretical. Thus, the “Total Theatre” Walter Gropius designed for Erwin Piscator in 1927 regularly features in narratives about theatrical experiments in this period, even though Gropius’s design was never realized; the drawings for the proposed building have been frequently reprinted. But the theatres in which Piscator actually put on all of his theatrical experiments with simultaneous stages and projections — the Volksbühne, the Staatliche Schauspielhaus, and, most extensively, the Theater am Nollendorfplatz — are rarely discussed in any detail. None of them, not even the relatively “democratic” Volksbühne, easily fit into the standard progressive narrative: they all were proscenium theatres. The Staatstheater, least progressive of all, was an imposing Neoclassical building designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel for the Prussian royal court. (One of Berlin’s theatres, Max Reinhardt’s Grosses Schauspielhaus, might be seen as a uniquely inventive space, with its Greek-theatre-style seating, hugely variable stage, and enormous capacity, but it never became an engine of theatrical innovation and was soon used exclusively for popular entertainments. I will therefore not consider it in this discussion.)

Piscator himself complained about the many ways in which these theatres hindered his ability to realize his stage experiments. Even the Volksbühne, one of the most technically advanced theatres in Berlin at the time, did not have the necessary equipment, and needed to acquire better projection devices to serve Piscator’s needs. The Theater am Nollendorfplatz lacked the Volksbühne’s permanent dome horizon and didn’t have a scene dock, making turnovers between rehearsals and productions immensely complicated (and costly). From the artist’s perspective, these were limiting spaces: the kind of theatre Piscator wanted to make could only have been staged in the kind of venue Gropius had envisaged for him. But from the perspective of theatre history, the kind of theatre that actually ended up being made is arguably at least as important — as are the actual spaces that provided the conditions under which it was realized.

The Theater am Nollendorfplatz in the early 1940s. (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 044, 10)

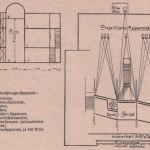

Take, for instance, Traugott Müller’s famous design for the production that opened the Piscatorbühne’s first season at the Nollendorfplatz house: Ernst Toller’s Hoppla, wir leben. A massive grid of iron tubes (3-inch gas pipes, in fact), weighing almost four metric tons, 11 metres wide, 3 metres deep, and over 9 metres tall, it created six small rooms, stacked on either side of a tall central chamber, which had a small, domed, eighth space on top of it. All eight chambers could be used and lit individually or simultaneously; each also did double duty as a projection screen. Those screens could be moved to the front of the chamber, allowing for invisible scene transitions behind them; they were also used for back-projections when the chambers were in use, those projections taking the place of all scenic paint work. Two sets of stairs on either side allowed external access and brought the total width of the structure to 13 metres. The entire edifice sat on tracks, so it could easily be moved closer to or further away from the audience, and it was placed on top of a revolve, so scenes could also take place on the stage in front of or behind it. Finally, in some scenes the proscenium was covered with a white and a black gauze drop onto which film was projected frontally, while the screen in the structure’s large central chamber was used for film projections from behind — on occasion, film clips would be projected simultaneously from front and back, with actors performing, spotlit, between the two projections. (For a very detailed analysis of this production, see Klaus Schwind, “Die Entgrenzung des Raum- und Zeiterlebnisses im ‘vierdimensionalen Theater’: Plurimediale Bewegungsrhythmen in Piscators Inszenierung von Hoppla, wir leben! (1927),” in Erika Fischer-Lichte, ed., TheaterAvantgarde: Wahrnehmung — Körper — Sprache [Tübingen und Basel, 1995], 58-88.)

-

- Müller’s model for the structure (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_467_F)

-

- Hoppla, wir leben, 3.1: the back of the structure, with a scene in a “small room” on a tilted platform in front of it; the backstage architecture and part of the proscenium are also visible. (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_585_F)

-

- Hoppla, wir leben, 4.1: in jail. Walls of the cells are back-projected and front-projected, the central chamber shows an image of a concrete wall. From the angle of the photograph, the structure almost fills the proscenium. (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_465_F)

-

- Hoppla, wir leben; not sure which scene this is, but the image shows how individual chambers could be isolated as playing spaces, the contrast between light and dark rendering the unlit parts of the stage and set almost invisible (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_468_F)

-

- Hoppla, wir leben, 2.2: election scene. Staged in front of the structure, with the image of a highly decorated German officer’s chest back-projected (or frontally projected?) onto the central chamber’s screen; multiple mobile set elements have been wheeled on for this scene that seems to fill all available space between the structure and the edge of the stage; the actor with his back to the audience downstage centre is right up against the prompter’s box. (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_586_F)

Piscator and Müller’s set was obviously a strikingly inventive design — it almost makes the kind of work Robert Lepage is doing now, 90 years later, look unambitious by comparison. But it was invented for and thus enabled by the Theater am Nollendorfplatz’s specific stage: the proscenium opening there was 10 meters wide and 8.4 metres tall; set back from the edge of the stage, the entire structure would have been visible. The revolve, with a diameter of 15.5 metres, was well wide enough for the set. Only three other theatres in 1920s Berlin had as large a proscenium opening: the Volksbühne, the Staatliche Schauspielhaus, and the Schiller-Theater. None of the others, even though some had larger stages than the Nollendorfplatz theatre, could have accommodated Piscator and Müller’s concept. Max Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theater is a case in point: its stage was considerably larger, as was its revolve (with a diameter of 18 meters), but its proscenium opening was (and still is) only 8.5 meters wide — too narrow to allow for the three chambers to be placed side-by-side with sufficient distance from the back projectors.

-

- Construction drawings by Piscator’s technical director Julius Richter: frontal view and floorpan of the structure, including placement of projectors. (Bühnentechnische Rundschau 1927/5, p. 9)

-

- Construction drawings by Piscator’s technical director Julius Richter: side view of the structure positioned to face the auditorium, showing placement of projectors and scrims/curtains. (Bühnentechnische Rundschau 1927/5, p. 8)

-

- The stage of the Theater am Nollendorfplatz, side elevation (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 044,07)

For all of Piscator’s griping about the venue’s limitations, in a very real sense his production of Hoppla, wir leben was only possible because this particular theatre was at his disposal in 1927. His declared goal may have been to “blow up the limited space of the proscenium stage,” but, paradoxically, it was the specific spatial conditions of a particular proscenium theatre that allowed him to pursue that project.

I have gone on at rather too great length about a single example, so let me get to my broader point: theatres are spaces designed with particular aesthetic and technical systems in mind, but they don’t enshrine those same systems. Over the course of their histories as buildings, they can accommodate entirely different, unanticipated aesthetic programs; they can be used in ways unimaginable to their architects. But they offer restrictions as well as opportunities. And the specific limits and possibilities they offer shape the theatrical imaginations of the artists that work in them. Shape, not control: of course artists have frequently rejected the spaces they inherited altogether; they have remade them; they have ignored them. But even so, those inherited spaces form a kind of base condition of theatrical creativity — and the differences between the inventory of such spaces in different cities and countries may be a significant factor in how theatre cultures develop their specific idiosyncratic histories. Let me make this less abstract.

By the 1930s, 13 of the 15 Berlin theatres regularly used to stage plays (rather than operas, or operettas, or cabarets, or variety shows, etc.) were equipped with revolves. The average stage was over 16 metres deep (ignoring the “Hinterbühne,” the backstage area not normally used for performance, and often significantly narrower than the stage itself) and almost 20 metres wide. And most of those theatres had fewer than 1,000 seats. Just for comparison’s sake, the London Old Vic’s stage was 15 metres wide and 10 metres deep and didn’t have a revolve; but the theatre had room for 1,800 spectators (nowadays, the stage is a bit deeper, at 11.6 metres, and the theatre only seats around 1,000 — but there’s still no revolve). In fact, the smallest theatre in Berlin then, the Kammerspiele of the Deutsches Theater — a venue established by Max Reinhardt specifically for modern plays and a more intimate style — had a stage over 13 metres deep, and a revolve, while seating just over 400; only FOUR London theatres had (and have!) deeper stages than that, and only one of those was equipped with a revolve (it no longer is). That theatre, the Coliseum, had room for six times as many spectators as the Kammerspiele, though. On the other hand, a venue such as London’s Ambassadors Theatre, with a capacity comparable to the Kammerspiele, had to make do with a stage barely half as deep, at 6.9 meters. NO stages as shallow as that were used for the production of plays in Berlin. A sense of what was normal also informed the public discourse: thus the stage of the Theater in der Königgrätzer Straße (today’s HAU 1), over 16 metres wide and almost 14 metres deep, appeared “extraordinarily small” to the author of a 1922 article about technical theatre innovations; I don’t know if anyone would have described the much smaller stage of the Old Vic in similar terms.

Theatre artists making new work under those circumstances could therefore expect certain spatial conditions: they could assume that their stage would be almost as deep as — and often deeper than — the auditorium; they could assume that they would have the use of a revolve; they could assume that they would have to contend with a relatively narrow proscenium opening, always much narrower than the stage’s depth. (That is another signal difference between the inventory of venues in Berlin and London: only a handful of theatres in London have a stage that is much deeper than the width of the proscenium; over half of London playhouses have a proscenium opening that is as wide as the stage is deep, or significantly wider.) Those specific circumstances would have been a key creative starting point for their work. It’s not that a director or a designer in a different location might not, say, devise a set that requires circular movement, just as a director or designer working on a very deep stage may decide to reduce its depth dramatically and work in an artificially shallow space instead. But the former is a decision that requires complex construction and has serious budgetary consequences: it’s unlikely that a revolve (just e.g.) designed and built for a specific production would be scrapped if the rehearsal process reveals that it’s not as effective or useful as director and designer initially thought. An artificial wall is easy to discard; a real wall cannot as easily be moved. Things and conditions present in a venue invite experimentation and testing out of ideas precisely because their use comes at no extra cost and does not require planning.

I don’t know how far I would want to push this kind of argument: are London productions in general, historically and now, more likely than Berlin productions to adopt sets and stagings that emphasize width over depth? I have no idea. But in specific instances, spatial conditions seem a clear and crucial factor in innovations in staging, as the material through, with, and against which new theatrical ideas are developed.

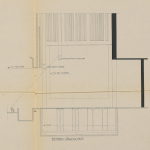

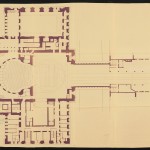

I wonder, for instance, if the fact that the Staatstheater, Berlin’s grandest and most important theatre of the Weimar years, did not have a revolve — and did not gain one until the early 1930s — may not have played a key role in the development of Leopold Jessner’s shockingly reductive stage aesthetics, the minimal, architectural sets for which “Jessnertreppe” (Jessner Stairs) almost instantly became an inaccurate shorthand. From the very start of his directorship of the Prussian state theatre in 1919, Jessner strongly propagated the importance of tempo in his productions, and wanted to avoid lengthy scene breaks; the space in which he worked was monumentally large, but lacked the equipment for fast changes between elaborate sets that filled the depth of the stage. However, after a major redesign completed in 1905, the Staatstheater had a side stage with a very large scene wagon, wide enough to completely fill the proscenium, and about 6 metres deep.

Genzmer, Felix (1856-1929), Schauspielhaus, Berlin. Reconstruction; floorplan. Note the deep and wide side stage on the right, which required extensive demolition and rebuilding work. (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum Inv. Nr. BZ-H 39,003)

Relatively shallow sets in front of a perspectival backdrop could thus be changed out quickly, but only at the cost of reducing the acting space to almost a third of the stage’s depth. Jessner’s approach, on the other hand, was to use most of the stage and add or remove simple, monumental structural elements upstage, downstage, or from above. In his 1920 Richard III, for instance, Emil Pirchan’s design initially consisted of little more than a tall upstage wall cutting across the entire stage (probably just downstage of the corridor on the right of Genzmer’s drawing), with a lower second wall in front of it: this formed an elevated platform and had a central opening which served as a gateway and as an interior space (for instance, as Clarence’s prison cell). After Richard’s rise to power, the famous stairs appeared, now running from the top of that wall towards the edge of the stage, painted blood red, widening progressively. I am not aware of an account of how this was accomplished, but the specific technical setup of the Staatstheater makes it likely that the stairs were waiting on the scene wagon and were simply moved in from the side stage. The lower of the two walls must thus have been at least seven or eight metres upstage of the curtain line, with nothing in front of it: no wonder Jessner’s stages were so often described as “empty.”

-

- The basic stage setup for the first three acts. The object downstage centre is the prompter’s box, with a light affixed to it. Both curtains and lights were used to cut triangular shapes out of the vast cubic emptiness of the stage and the proscenium opening; all surviving photographs and drawings suggest that the curtains remained slightly drawn for the entire show, narrowing the proscenium to perhaps 7 or 8 metres (instead of the maximum possible 10). Photo from Leopold Jessner und das Zeit-Theater, ed. Felix Ziege (Berlin 1928), 18.

-

- Pirchan’s drawing of the encounter between Richard and Anne (1.2), showing the use of the curtains and the contrast between the high upstage wall and the brightly lit cyc behind it — here green, later bright red. (Theatergeschichtliche Sammlung Universität Kiel, http://museen-sh.de/Objekt/6885262/lido/piri03)

-

- The basic stage setup for the final two acts: the famous stairs, widening as they approach the proscenium (thus creating an illusion of greater height and recession); the third, narrowest set of steps continues uninterrupted from the top to the bottom; there are no enlarged platforms in front at the points where the steps widen. Photo from Leopold Jessner und das Zeit-Theater, ed. Felix Ziege (Berlin 1928), 17.

-

- Pirchan’s drawing of Richard’s coronation; the number of five retainers on either side of the stairs is confirmed in other contemporary drawings — as stark as Prichan’s/Jessner’s stairs were as a set element, they were not quite as enormous in size as some accounts imply. (Theatergeschichtliche Sammlung Universität Kiel, http://museen-sh.de/Objekt/6885262/lido/piri01)

The critic Max Osborn identified as particularly revolutionary Jessner’s ability to understand and shape “the cube of the stage” — and what a cube he had in the Staatstheater, almost 20 metres deep, 26 metres wide, soaring over 21 metres high below the grid, and with the second-tallest proscenium arch in the city at 8.4 metres: almost 11,000 cubic metres of space. Of course there were means of reducing the sheer presence of that empty space, rendering it dynamic, breaking it up into smaller units, making it feel smaller. Neither Schinkel nor the architect overseeing the 1904 reconstruction, Felix Genzmer, had intended all that emptiness to be made visible. But the space was there, as a challenge, and as an opportunity — and in the absence of a revolve, it was a space that almost demanded to be taken seriously as a whole, to be “understood” and “shaped” in its totality.

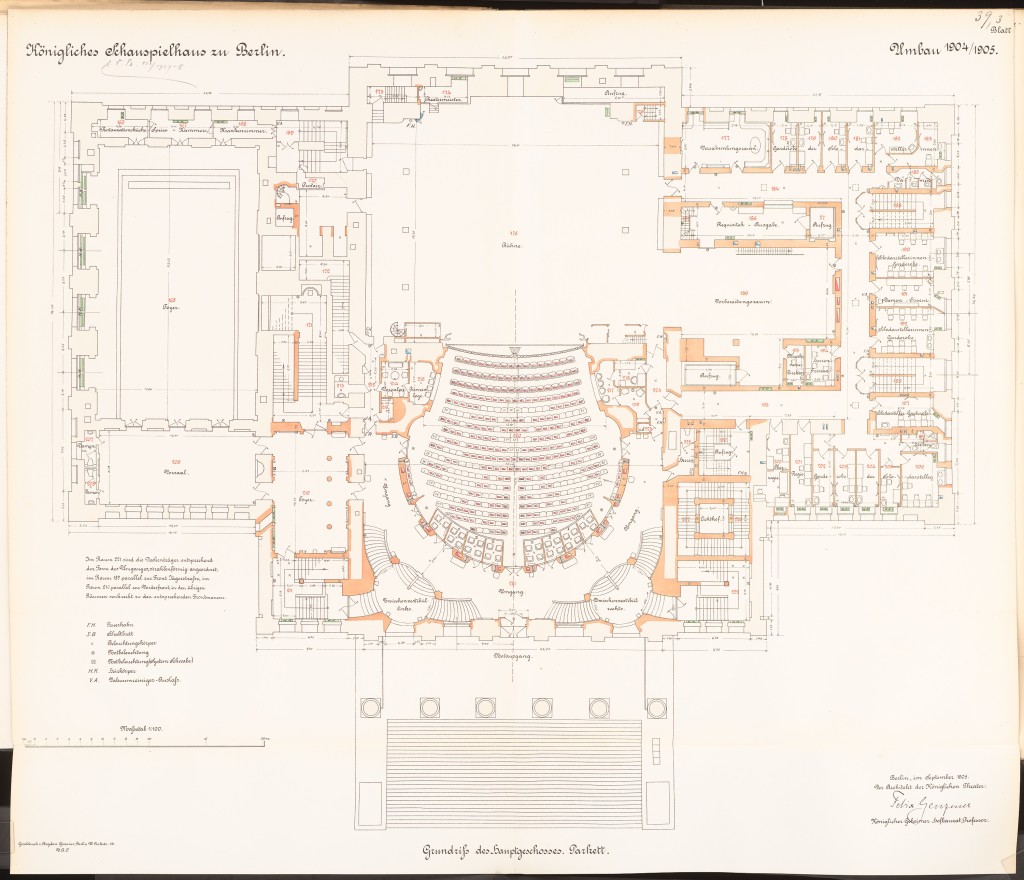

That space changed dramatically in 1935, when Hermann Göring, in his role as Prime Minister of Prussia and particular patron of the Staatstheater, commissioned a massive reconstruction project. This involved replacing the existing houses behind the theatre, across the Charlottenstrasse, with a large storage and construction facility for the theatre, which was directly connected to the backstage wall by a covered bridge through which preassembled scene wagons could move on two sets of tracks. This bridge became, in effect, an enormous new backstage area, over 21 metres deep, over 11 metres wide, and almost 9 metres tall. Theoretically, with all the gates wide open, spectators seated in the middle of the stalls or the first circle could have seen all the way to the back wall of the storage building, over 80 metres beyond the proscenium. The goal of the reconstruction effort was not to create an impossibly deep stage, though. It was to equip the Staatstheater with the machinery necessary to combine elaborate, lavish Realist sets with the greatest possible efficiency and speed for scene changes. A large revolve was installed, which, combined with the two scene wagons on the backstage tracks and the side stage that was retained, allowed for up to four separate sets to be assembled and made ready independently. The new facilities would allow for film-like scene transitions.

-

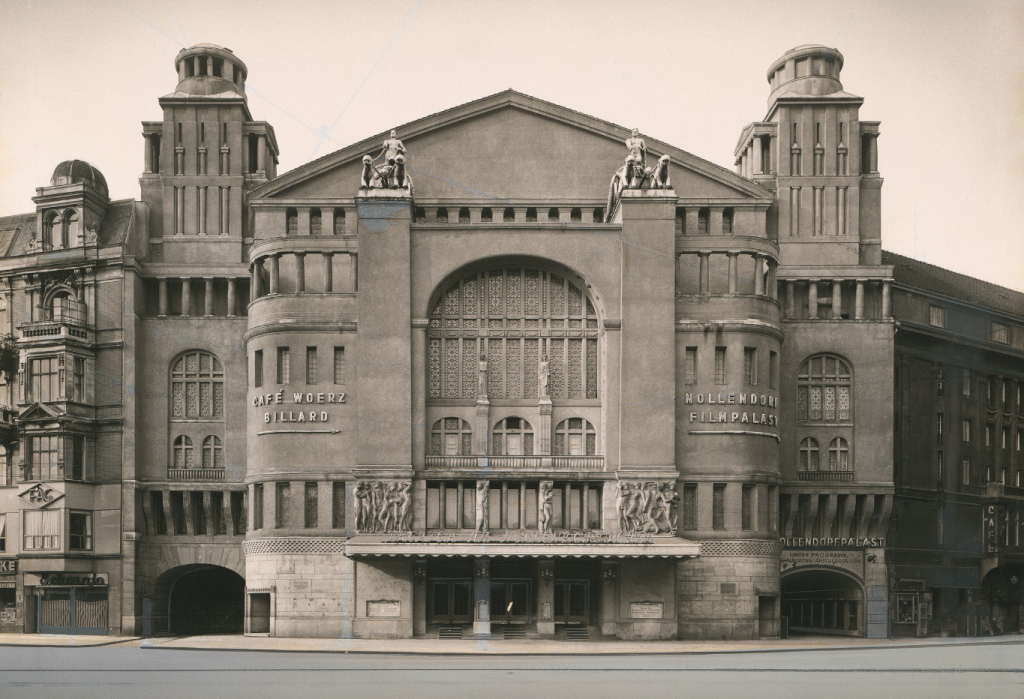

- Floorplan of the reconstructed Staatstheater, showing the parallel tracks for scene wagons running from the stage to the storage facility on the right (and making obvious how much larger the stage and backstage areas are than the auditorium!). (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 039, 5)

-

- Floorplan of the new stage, showing the extremely deep backstage space and retained side stage (slightly reduced in size). (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 039, 7)

-

- Side elevation of the new stage, showing the extensive array of lifts integrated into the new revolve. (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 039, 7)

-

- The covered bridge between the Staatstheater stage and the new storage and prep facility on the other side of the Charlottenstrasse. (TU Berlin Architekturmuseum, Inv Nr TBS 039, 12)

-

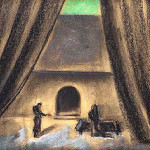

- An aerial image of the area around the Gendarmenmarkt and the Staatstheater in 1942; the new storage facility is highlighted.

And yet, when Jürgen Fehling directed Richard III on this new stage, he ignored all those technical innovations, with the exception of the new depth of the space. An emptiness almost designed to remind audiences of Jessner’s — in 1937, seven years after the Jewish Social Democrat Jessner had been driven from office by reactionary critics and four years after he had fled Germany once the Nazis came to power. Paul Fechter described it as a “luminous box of space” that forced “one’s gaze far into the gigantic depths of this stage” — the raked floor painted in a light colour, the walls covered in bright cloth, steps far, far upstage descending who-knows-where, and finally, another bright cloth wall at the very back. As Hans-Thies Lehmann reports, some reviews vastly misjudged the depth of the set, thinking it to be almost twice as deep as its actual (and already unprecedented) 44 metres: that space, as remarkable as the production was for other reasons, was its most sensational and immediately overwhelming feature. Fehling and his designer Traugott Müller (of Hoppla, wir leben fame!) did not exactly transform an old space for new purposes, of course: their theatre still smelled of fresh paint. But they took a facility constructed for one kind of theatrical aesthetics and used it — exposed it, really — in the service of an aesthetic program diametrically opposed to the Nazi theatre functionaries’ intentions. No one wonder Göring apparently left in the first intermission, muttering about “cultural bolshevism.”

-

- The meeting of Richard and Anne (1.2) — contrast this with Jessner’s staging! The long line of Anne’s retinue snaking forward for almost 40 metres makes the most of the funnel-like depth of the space.

-

- 3.7: Buckingham and the Lord Mayor “pleading” with Richard. In Jessner’s production, Richard and his priests appeared on top of the wall, above the central doorway: this would also become, once the stairs were in place, the site of Richard’s coronation. In Fehling’s version, Richard never reaches a higher place than this balcony, suspended precariously from the stage left proscenium tower. His coronation platform is much closer to the ground. (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_520_F)

-

- Richard’s coronation, much closer to the ground than in Jessner — and also one of the most crowded stage pictures of the entire production; the space is never as shut down and as shallow as this elsewhere. (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_521_F)

-

- Towards the end of 4.4 — Richard is about to go to battle with Richmond. The space is as bright, cavernous, and empty as it could be, his supporters mostly squeezed against the stage left wall. (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_522_F)

-

- 5.7: Richard solus, about to encounter Richmond. (They won’t fight. Richard will drop dead as soon as Richmond raises his sword.) The streamers of painted cloth lowered from the fly, close to the stage floor, to suggest heavy cloud cover further enhance the visual pull towards the far-off back wall: they almost seem to be sucked into the deep. (Institut für Theaterwissenschaft der FU Berlin, Theaterhistorische Sammlungen, Nachlass Traugott Müller, sig. IfT_TM_620_F)

The 1935 reconstruction of the Staatstheater was the opposite of an avant-garde project. But despite its reactionary purpose, it created new possibilities for artists to reimagine theatrical space. Just as Jessner’s productions put a theatre built for a king in the service of a radically reduced aesthetic and a Republican ethos, just as Piscator turned a standard proscenium venue into a site for technical, theatre-aesthetical, and political radicalism, Fehling pushed Jessner’s spatial thinking further and played with political fire on the very stage designed as the Nazi state’s most impressive theatrical venue. All three of the shows I have discussed could only have been staged in the kinds of theatres where they were staged; but none of those theatres were designed with these kinds of shows in mind. They became avant-garde theatres in the hands of avant-garde theatre makers.

Of course innovation in the theatre is sometimes driven by new plays or new spaces. But as often as not, theatre reinvents itself through an engagement with old things: old plays, old styles, old rooms. Even the theatrical avant-garde has a habit of looping back, of looking backwards to go forwards. In that sense, there is no contradiction at all in making radical art in traditional spaces. It is simply the kind of thing theatre tends to do. But as theatre historians, we need to pay attention to both where those radical artist went in their work and to the seemingly negligible traditional places (and plays) where that work took place, and by which that work was enabled — because even though the artists may not say so, and though it may not be obvious, the work would have been different in different spaces. Theatre is always local, in its making and in its reception; and if we don’t understand a production’s specific local preconditions, we can’t really understand the process of its making, the nature of its reception, or, ultimately, the work itself.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.