Monday, 6 January 1919

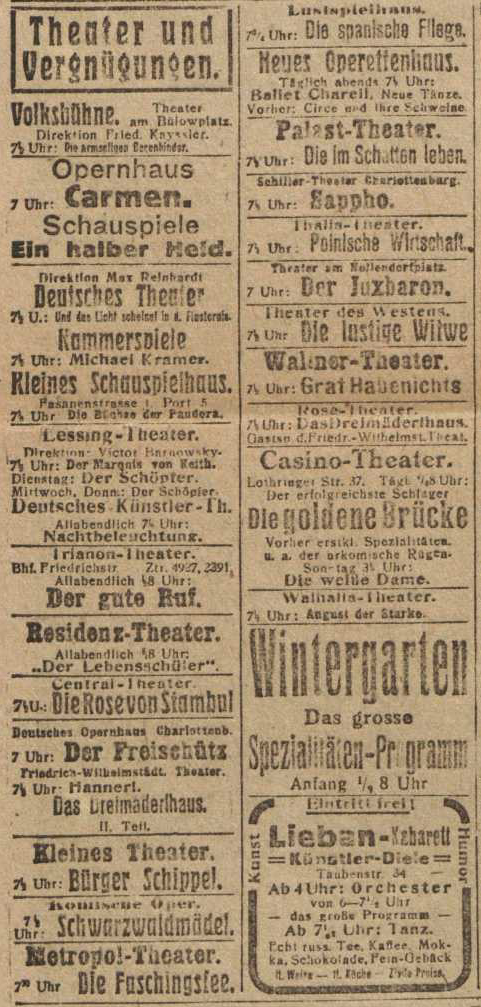

Not an ideal date to start this project! 6 January 1919 was the day after the beginning of the uprising that became known (inaccurately) as the Spartacist Revolt (the English Wikipedia entry is not exactly sound historiography, but it’ll have to do), and many newspaper offices were occupied by protesters, including those of the Social Democrats’ party newspaper, Vorwärts. It so happens that Vorwärts is one of my main sources for the project, as all its issues have been digitized in colour — and on 6 January, although the workers occupying the building did publish an edition, it came without any ads, including the theatre announcements. Luckily, Freiheit, the Independent Social Democrats’ newspaper did appear, and has been digitized in colour as well — so here’s the day’s theatre programming from that source:

It’s not a complete listing, though. So let’s supplement it with one from the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung (which doesn’t include some other theatres that do appear in Freiheit):

No Shakespeare, I’m afraid. But isn’t it remarkable? The day after a massive armed demonstration, the day before a general strike that half a million of Berliners took part in, while many of the city’s newspaper offices were under occupation — in a city in profound civic unrest — the theatres carried on regardless, offering the usual mix of light opera, farces, cabarets, new “serious” drama, and opera. The only thing missing this day, a mere coincidence I am sure, was classics.

A few spotlights:

Max Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theater staged Tolstoy’s The Light Shines in the Darkness, directed by Reinhardt himself (it had opened on 13 December of the previous year and would eventually see 79 performances), with two of the theatre’s biggest names in the cast: Alexander Moissi and Lucie Höflich.

The Staatstheater’s Schauspielhaus — no longer the royally patronized theatre, but not quite yet the new democratic Prussian state’s own theatre either, run on a temporary basis by two not-especially-distinguished directors — opened a new show, a now-forgotten play by a now largely forgotten playwright: Herbert Eulenberg‘s Ein halber Held, a tragedy set in the seven-years war. The Börsen-Zeitung‘s review the next day highlights a moment of deep reactionary appeal: as an officer prays for his fallen soldiers, he closes his prayer with “May Prussia never fade nor waste away until the end of days.” The reviewer reports there was “a breathless pause; then thunderous cheers that go on and on echo through the auditorium.” And he approves: “In other theatres this response may not have occurred, in others yet there may even have been protests. But the cheers in this venue had the quality of a release, of uplift: there still are people who will dare to make a public demonstration in favour of Prussia’s fate, whose hearts are warmed by a prayer for Prussia’s future.” The politics of the scene had little to do with the play, which, the reviewer thinks, may even be considered “anti-Prussian” — but the moment in isolation resonated strongly, in the context of the day’s events, for an audience and a critic that likely shared few of the Socialist protesters’ views and goals. The lead was played by Theodor Becker, soon forgotten too. But another (unidentified) role was played by Maxim Vallentin, who in the early years of the GDR would become one of the main proponents of Stanislavskian ideas and was the first artistic director of the Maxim-Gorki-Theater.

The only plays still recognizable now: two by Wedekind, Der Marquis von Keith and Die Büchse der Pandora. Both were significant productions: the former, directed by Victor Barnowsky (the most neglected of major Berlin theatre figures), marked the first appearance of both Elisabeth Bergner and Eugen Klöpfer on Berlin stages when it opened on 23 October 1918: Bergner would go on to be one of the most adored actors of stage and screen in Weimar Germany, until she had to flee the country in 1933 (two years later, she would appear as Rosalind, with Olivier as Orlando, in the first spoken-word Shakespeare film shot in England — a role in which she had been celebrated in Berlin over a decade earlier, under Barnowsky’s direction). Klöpfer, on the other hand, was happy to stay in Germany, became a high-ranking functionary in the Reich’s theatre organization and the artistic director of the Volksbühne in 1935, joined the party in 1937, and acted in antisemitic propaganda films including the infamous Jud Süß. In his diaries, Goebbels frequently expressed his admiration for Klöpfer’s work.

Die Büchse der Pandora, one of the Lulu plays, directed by Carl Heine, would wind up in Reinhardt’s Kammerspiele the next season and starred Emil Jannings and Werner Krauss, both destined to be huge stars on stage and screen (and in Krauss’s case, a hugely problematic figure after 1933). In 1929, the play was turned into a film with Louise Brooks and Fritz Kortner. And there’s Gerhart Hauptmann’s Michael Kramer (directed by Felix Hollaender, who would soon take over as artistic director of the Deutsche Theater from Reinhardt, with a starry cast including Paul Wegener, Ernst Deutsch, and Elsa Wagner; it had opened on 3 December 1918). And, of course, Weber’s Freischütz — but I suppose the operatic repertoire has remained more stable over the past 100 years than that of other kinds of performance art.

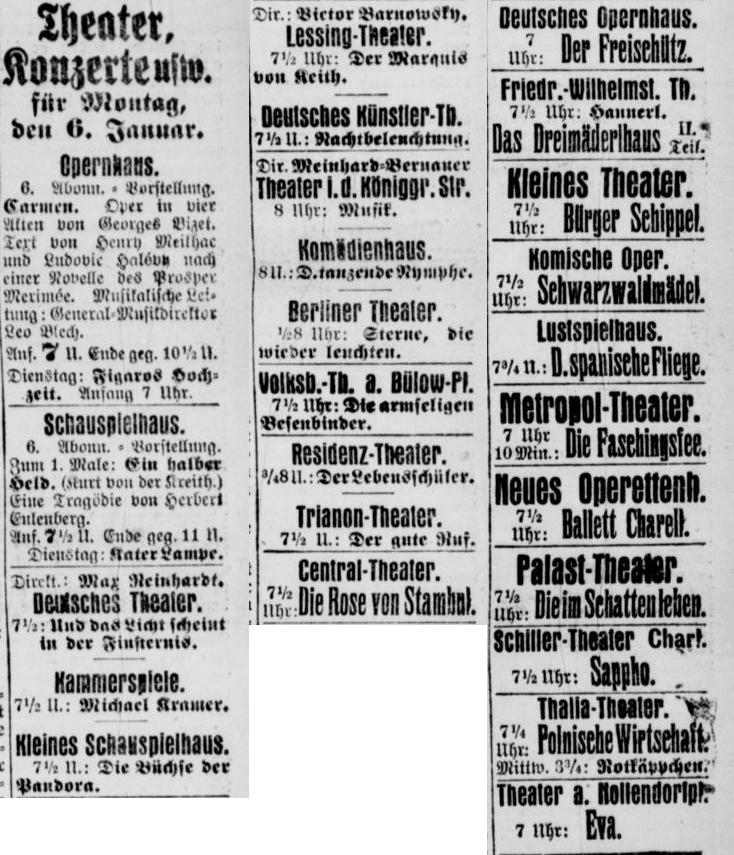

Die spanische Fliege at the Lustspielhaus, a popular farce by Franz Arnold and Ernst Bach, disappeared into obscurity after the 1950s. In 2011, though, it was resurrected, to great critical acclaim, by Herbert Fritsch at the Volksbühne — a production that was invited to the 2012 Theatertreffen as one of the ten “most remarkable” of the year.

Die (s)panische Fliege, dir. Herbert Fritsch (Bastian Reiber, Wolfram Koch, Harald Warmbrunn, Hans Schenker, Sophie Rois). Photo © Thomas Aurin.

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

- Tim Keenan on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Holger Syme on 1920s Berlin Theatre: Research Marginalia 1

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.