Friday, 10 January 1919

It seems as though there was less outright street fighting this day, more a tense atmosphere of expectation — the occupants held firm but were awaiting an attack by government troops. At the same time, the unrest was now spreading through the entire country, with mass demonstrations and occupations of newspaper offices elsewhere in Germany. And finally, after five days, it looks as though the theatres have been affected: the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung reports that two premieres planned for Friday night have been postponed: the Deutsche Theater is not opening Georg Kaiser’s Von Morgens bis Mitternachts, announcing a postponement until next Wednesday (in the event, it wouldn’t in fact open until 31 January, and then only ran for five performance). And on the opposite end of the artistic spectrum, the fantastically orientalist-sounding Geisha at the Wallner-Theater is also being put off, with no new opening date announced. Both theatres instead extended the runs of their current productions — Tolstoy’s The Light Shines in the Darkness in Reinhardt’s house, the rather less distinguished operetta Graf Habenichts (“Count Have-Nothing”) at the rather less distinguished Waller-Theater.

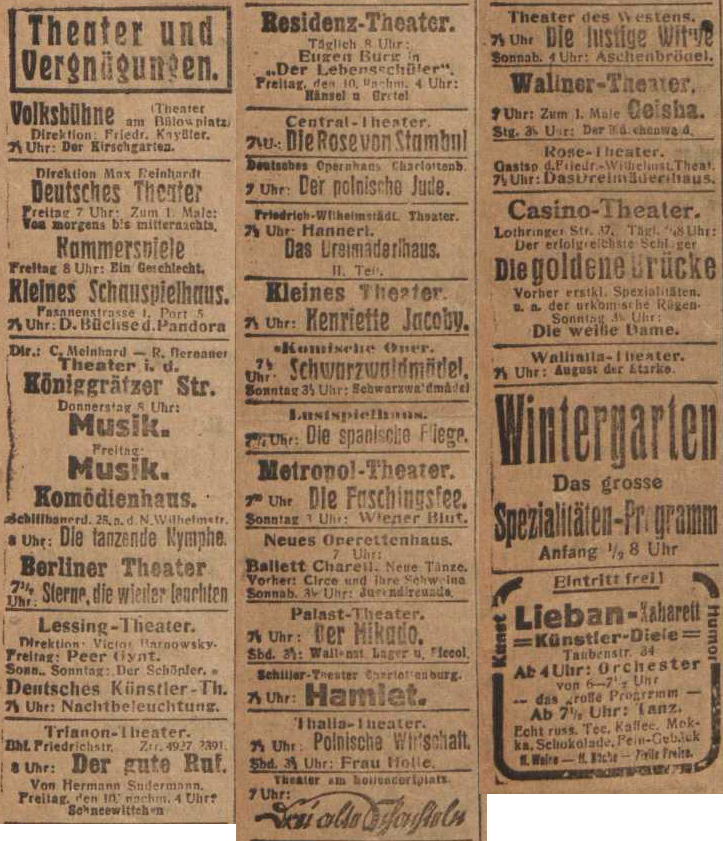

The only theatre listings for this day are from Freiheit (with both of the postponed shows still listed):

Lots of new titles from the repertory, and one opening (though it’s not listed here): Ibsen’s Ghosts at the Staatstheater. The Volksbühne is offering its staging of Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard; Barnowsky’s Lessing-Theater has a Peer Gynt that had to compete with a juggernaut adaptation of the play at the Staatstheater, which ran over 700 times between 1914 and 1930; and the Schiller-Theater in Charlottenburg brings back its Hamlet, which had premiered in late October 1918 and would see a mere 5 performances this year before being retired. At the Kleine Theater, it’s sequel time: Henriette Jacoby was Georg Hermann’s follow-up novel to Jettchen Gebert, also turned into a play by the author, and also was filmed in 1918 — I suspect what we’re seeing here is a theatre piggybacking onto the commercial (and artistic?) success of a two-part film. An inauspicious title at the Deutsche Opernhaus: Der polnische Jude (“The Polish Jew”); yet as far as I can see Karel Weis’s opera is not as antisemitic as the title might suggest, but rather the story of a Christian inn keeper who murders a Jew seeking shelter.

With so many newspapers affected by the uprising, no reviews of the Staatstheater Ibsen appeared in any of the sources available to me — even the papers that did appear seem to have ignored it. Perhaps it didn’t seem an especially exciting occasion: Ghosts was frequently staged in Berlin in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Before Reinhardt became a director, he appeared in it at the Deutsche Theater for two years, from 1900-1901; he then mounted his own production with set designs by Edvard Munch in 1906 as the opening show in the new Kammerspiele. Between then and 1910, that version frequently returned to the repertory at the Kammerspiele and also in other theatres he owned; In January 1918, it transferred to the Volksbühne as well. At the same time, the play had been in rep at the Lessing-Theater, on and off, from 1908 to 1912, directed by Emil Lessing; Victor Barnowsky staged his own take after his took over the Lessing-Theater in May 1916, and revived that show in October 1918. It may just not have been a production of such burning importance to attract immediate critical attention in the midst of armed unrest. When reviews eventually did appear, days later, they focussed almost exclusively on the actors’ performances, revealing little to nothing about the show itself. Alfred Klaar, in the Vossische Zeitung, wonders if the impressive crowds at the theatre are seeking a homeopathic remedy, healing the pain of recent days by exposing themselves to a milder — or fictional — form of turmoil. In any case, the kinds of people who go to the Staatstheater, he thinks, may in fact be new to Ibsen’s play: “the audience members here don’t change as often as the artistic directors.” That’s a running theme in many reviews of Staatstheater production in these months: it’s a dusty old pile full of dusty old people, and all of that is about to be shaken up. Klaar is kind: the production understands Ibsen, to his mind, the actors are acquitting themselves fine, and the new material seems to have sparked some energy. The Börsen-Zeitung‘s critic isn’t quite so nice: they’re working hard at the Staatstheater, he concedes, but the evening isn’t up to snuff in a city full of Ibsen aficionados and experts, onstage and off. Tepid critical opinion notwithstanding, these Ghosts remained in the theatre’s repertory until 1930, ultimately appearing on stage 86 times.

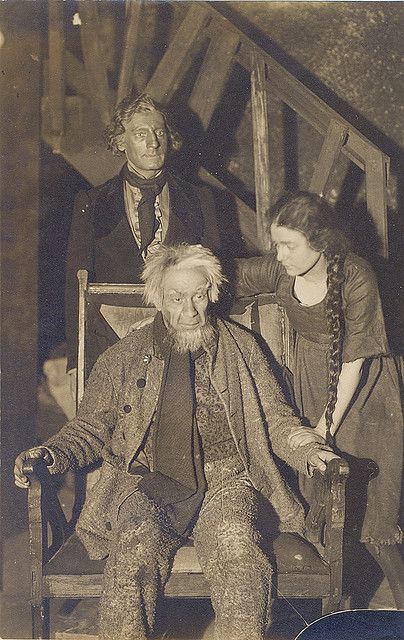

The Volksbühne’s Cherry Orchard was the German premiere of Chekhov’s play; it had opened on 9 October 1918. (Stanislavski’s MAT production toured to Berlin in 1922, when it was received as piece of living history — museum theatre. Herbert Iehring responded with deep ambivalence at that time, lamenting that Stanislavski’s “art shows no development at all. It stands before us as a completed whole, showing its beginnings and its end together. The art of theatre, more self-consuming than all the other arts, has never preserved itself as much as here. It is already a piece of history, though it is still effective.”) Directed by Friedrich Kayßler, far more talented as an actor than as a director, it starred the young Jürgen Fehling as Trofimov, far more talent as a director than as an actor (and destined to become one of the most important directors of the next two decades). Reading the reviews makes for a very odd experience from our historical vantage: Chekhov was still largely unknown in Germany, especially as a playwright. Adolf Lapp, in the Tageblatt, introduces him as “Anton Chekhov, the author of novellas;” the review in Vorwärts misinforms its readers that “Anton Chekhov only wrote two plays.” Given how routinely Chekhov and Shakespeare get lumped together now as the two most “universal” playwrights, it’s also striking to see complete agreement across all the reviews that The Cherry Orchard is a deeply “Russian” play, about a very specific, historically concrete Russian situation, populated by very particularly Russian characters. The set — generally praised, though unfortunately not in especially specific terms — works because it is the result of a “deep immersion in Russian circumstances and Russian people,” the Vorwärts critic argues; Lapp reads the sound of the cherry trees being chopped down at the end, “this lonely, sad thumping” as “strange and mysterious, like the last painful beats of a heart. It is the heart of the cherry orchard, but perhaps it is more, might be the heart of Russia, struggling with tremulous, convulsive beats for repose.” (Franz Köppen, in the Börsen-Zeitung, while acknowledging the literary and “ethnographic” strengths of the text, considers it essentially incomprehensible to anyone without a deep understanding of Russian culture!) And there’s widespread puzzlement about the dramaturgical recklessness of the play: Lapp calls it “odd” and “entirely unconcerned about theatrical effectiveness”; Köppen a “lyrical poem” “wholly focussed on atmosphere,” which “resists being captured by the stage”; even Stefan Grossmann, in a rapturous review (in the Vossische Zeitung), finds the lack of conventional dramaturgy amusing: “What kind of mini-conflict [Konfliktchen] is this?” They’re not wrong, of course, but it is fascinating to read these first, slightly bewildered encounters with a play that has become such a staple of our modern repertory! Much of what the reviewers say also happens to be extremely perceptive. The critic for the Berliner Volks-Zeitung’s analysis of the “tragic” situation, for instance: “It is true, after all, that the cherry orchard was indeed largely useless — they couldn’t even figure out what to do with all those cherries — it was useless like the people that loved it and owned it. So let’s get rid of it, right? And Chekhov smiles a ‘yes’ full of boundless bitterness.” Or Grossmann’s notes on Chekhov’s dialogues, which really are “interwoven monologues”: “Everyone really only lives in their own imagined worlds and barely hears a few key things from the isolated worlds of the others. That is the source of the melancholy and the humour of Chekhovian dialogue. These people talking past one another is deeply tragic and enormously comic at the same time.” I’m not sure I disagree with a word of that. The production receives universal acclaim, even from the skeptical Köppen, who thinks the play gives the actors so little to do that their relative success is all the more remarkable; Grossmann considers it “simply a perfect staging.” One final observation. No one seems to have found Trofimov’s ideas worth discussing, and no-one described Lopakhin as anything other than a”money man,” a heartless, almost inhuman figure. But Firs! The Volks-Zeitung singles Guido Herzfeld’s performance in the part out — a performance that “in the end, was devastating to an extent that words cannot capture.” Lapp, too, found Herzfeld’s Firs “unforgettable and incomparable especially in the shattering death scene.” So Firs, in this staging, unequivocally died. And became the emotional centre of the production.

Not from The Cherry Orchard, but that’s Herzfeld in the centre.

I’d love to say something about Barnowsky’s Peer Gynt, but will leave that for another time. As for the Schiller-Theater’s Hamlet, I wish I had things to say. But as with most productions at that theatre — a venue in Charlottenburg, built by the city for the express purpose of bringing stagings of classics and “folk plays” to the middle class denizens of this then independent municipality — it was mostly ignored by the critics. What reviews there are tell of a “worthy” effort — “clear,” “dignified,” “at times surprisingly strong.” The most remarkable aspect of the production may have been the fact that its Ophelia (whose name is variously reported as “Ms Brohm” and “Ms Brohne” died a few days before the opening, a victim of the flu epidemic. On that occasion, in October 1918, she was replaced by Hilde Coste, a member of the Staatstheater ensemble; but later in the run, a different actor must have been found, as Coste was in the cast of Ghosts at the Staatstheater as well. The most powerful scene, not coincidentally, seems to have been Ophelia’s funeral. One reviewer at least saw an original take on the title role, a Hamlet “not adrift, ‘sicklied o’er by the pale cast of thought’, but superior, disgusted by the rot all around him. … This Hamlet was full of passion, alive with cutting satire, animated by grim humour.” It’s an intriguing thought: on the fringes of Berlin’s theatre world, in a mostly ignored production, a Hamlet seems to have made an appearance that anticipated the “man of action” reading of the character that would become the favoured interpretation in Nazi Germany!

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Recent Comments

- Die Berliner Volksbühne: Ein Zentrum für politisches und experimentelles Theater - Kunst 101 on What’s so special about German theatre: Part 1

- My Homepage on Shakespearean Mythbusting I: The Fantasy of the Unsurpassed Vocabulary

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on My Trouble with Practice-as-Research

- Premodern Performance-based Research: A Partial Bibliography – Alabama Shakespeare Project on Where is the Theatre in Original Practice?

- Alex on Steven Moffat, Sherlock, and Neo-Victorian Sexism

Archives

- November 2021

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- July 2017

- May 2017

- March 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

Copyright

Holger Syme's work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.Images may be reused as long as their source is properly attributed in accordance with the Creative Commons License detailed above. Many of the photos here were taken at the Folger Shakespeare Library; please consult their policy on digital images as well.